Graham Reid | | 9 min read

Alright, here’s one for old folks. Don’t you wonder what ever happened to Chris Jagger? Yes, Mick’s brother - you must remember him, he launched his own recording career somewhere back there in the late 60s. It was around the time Fred Lennon (yep, John’s dad) released his first - and only -- single.

OK, that’s cruel, but you have to

sympathise with these people. When it's all happening for someone in

your family, why shouldn't it happen for you? Same environment, same

genes, right?

In some families this fame thing comes

easily though. Like The Jacksons - whew, that Michael; wow, that

Janet. Hot stuff.

But maybe they are too studio-coiffured

and video-crafted. Then look to a music where the playing is put up

front -like jazz, for example. And the family which is doing it? The

Marsalis mob from New Orleans who are hot, committed and

controversial.

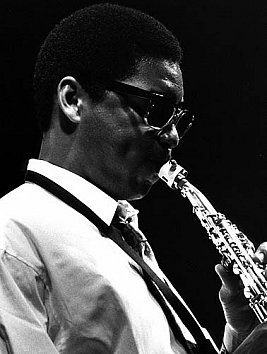

Brother Branford is known in some

circles as Sting’s sax player and in others as a pretty sharp jazz

musician on to his fourth album under his own name. Then there is

brother Wynton, the trumpeter hailed in some quarters as the new

Miles Davis but a bit of a reactionary intent on doing down any

musician he sees as demeaning the purity of acoustic jazz.

Yet another brother, Delfeayo, has done

production on Branford's albums and most recently the new one by

Courtney Pine, an English sax player in the vanguard of Britain‘s

new crop of smart-suited saxists.

Maybe such careers came easy in the

Marsalis family however. Their father Ellis is a highly regarded

pianist and academic in New Orleans. Quite a family.

And somewhere in there is Mrs Marsalis

-- a woman who obviously has a story of ber own to tell.

Speaking from his home in New York on

the eve of Sting's Australian tour and the release of his new album,

Random Abstract, Branford Marsalis is (like brother Wynton, who

proved an amiable if single-minded cuss at the Festival of Arts in

March) cheerful and easygoing.

He’s putting together a tape for a

party on Saturday and has just finished recording Marvin Gaye’s

Let‘s Get It On.

“Nobody listens to Marvin any more.

This hip-hop stuff is killing society," he laughs. "I like

some of it -- like Public Enemy - but I don't see it as a viable

alternative to real music. It's a cute little entertainment thing but

l figured it would die about three years ago, so I’m not predicting

any more."

Unlike brother Wynton, who has so

deeply immersed himself in jazz he admits he can't name 10 rock

albums, Branford is entirely comfortable with rock music - up to a

point.

“I always liked Sting’s music. It's

exciting and I loved the Police, so this was a chance for me to play

some rock'n'roll - but rock with class.

“A lot of people say what they like

about rock is the freedom, that reckless abandon where you don’t

have to feel responsible - like heavy metal. That’s cool for people

who want to do that. But for me it isn’t my thing, so when l finish

this tour I’m done with pop.

“As a jazz musician you have to work

hard to get a lot of technical things together in your playing but

you lose them in a short time just playing pop.

“For a while it din't bother me but

when you try to play jazz again it doesn't work - and that hurts.“

During the Sting years he hasn't been

entirely away from jazz, however. He recorded two albums, Renaissance

and the new Random Abstract, in that time and also worked with Herbie

Hancock's band.

The critical reception given to his two

albums has been favourable, but hardly ecstatic.

The standard line is he is moving at an

achingly slow speed towards finding his own sound, and while no one

will dispute his dazzling technical skills, he has often sounded like

the sum of his influences rather than his own man. Echoes of past

masters like John Coltrane, Charlie Parker, Ben Webster and Wayne

Shorter all haunt his playing, and the new album is no exception.

In fact, Random Abstract gives even

more ammunition to critics as he deliberately plays material in the

Shorter, Coltrane or Webster manner.

But 27-year-old Branford is prepared

for the snipes and comments. He’s seen it all before - with Wynton.

“I was lucky to be a first-hand

witness to see what happened to Wynton, but critics' opinions really

don’t matter all that much. I wasn't particularly interested, nor

was I ready to rush into some new unique style.

"You could say I sound like

Coltrane or Webster -- but how many other people do you know in my

age bracket who could put out the records which sound like a bunch of

different guys? You can’t name them."

He goes on to say how great saxophone

players like Sonny Rollins and Wayne Shorter have shown him how they

can play in the styles of other artists but also create their

own-voice. He feels he is still exploring the long legacy left by

earlier players and on his way to discovering his own style.

“You know Dizzy Gillespie tells me

I'm doing good so I should keep it up, Sonny calls and says it's

alright and Dexter Gordon leaves a message on my answerphone which

says, ‘I hear what you are doing, keep the fire burning’.

“All the musicians say I’m a good

player and some critic tells me I suck – now who am I going to

believe?” he asks with a laugh. `

He excuses himself from the phone to

choose some more music for his party tape and is back within seconds.

“I’ve got that Atlantic Rhythm and

Blues re-issue set so I think I'll put down a little something by the

Coasters and . . . oh . . . the Exciters, I just love them," he

says with delight. But he doesn't leave the phone to do it. He

manages the manoeuvre via his hi-tech remote.

“Every time I come home I add to my

stereo,” he says by way of explanation. “Now I’ve got a DAT

machine, a CD, three VCRs, three cassette players and I’m

constantly taping music, learning music and making music.

“I look forward to coming home for an

extended period. I’ve been on the road for about three-and-a-half

years now so I love to get home and buy some records. And you can't

practice on the road."

He places special emphasis on the wort

"home," and gossip has it that being married and with a

family has given this particular Marsalis a stable base to work from.

Plans to bring him to this country for

a concert after the Sting tour of Australia fell through because he

wanted to get home for his son’s fourth birthday, the first time he

will have been home to help light the candles on the cake.

The fact he is off the road after this

Sting tour, and talking of forming his own jazz quartet to make that

great leap with original material and a sound he can call his own, is

good news for those who have been patient enough to follow his slow

progress so far.

"The things I have been playing

are great but I am definitely moving on and so Random Abstract is a

farewell. I‘m writing more of my own stuff and I'll still do

classical things because I haven’t explored that area as much as

Wynton,” he says, referring to his own Romances for Saxophone and

his brother's four classical releases.

The band he talks of forming has a

dream line-up. On piano will be his long-time offsider Kenny

Kirkland, who has done the Sting routine as well as appear on

Branford and Wynton albums; bassist Bob Hurst and drummer Jeff “Tain”

Watts, both Marsalis insiders for many years and who have appeared

with both Wynton and himself.

Talk of working in a band takes him

back to the 10-month touring band he had with Julian Joseph on piano.

Joseph is now at Berklee college in Boston “doing it the way it

should be done", says Marsalis, by which he means study and deep

involvement in all the playing and academic aspects of jazz.

And that is very much the Marsalis

family line: study hard and immerse yourself in the tradition.

“When Wynton was doing those Mozart

records he had every book on Mozart so he could interpret the music.

That's what Julian is doing now and that’s why I don‘t agree with

Courtney Pine," he says preparing to speak about the hot young

English sax player who, like the Marsalis brothers, comes on with a

keen dress sense and a thick press-kit.

“Courtney believes he can play jazz

and live in England without having been to America. I don‘t think

it works. Jazz is based on the American heritage seen from a black

perspective. Keith Jarrett can do it with Jan Garbarek and make it

into a European perspective - and that’s hip. But Keith is the only

one in the band with the American perspective. I love it, but it’s

not what we do.”

Curiously, his interpretation of

Ornette Coleman's Lonely Woman on the new album is done deliberately

as Jarrett and the icy Norwegian saxist Garbarek would do it. Lonely

Woman, however, is a very old Coleman tune dating from the 50s.

Recently Coleman has made more challenging music which he calls

"harmolodic”.

Branford - like Wynton, who rages

against the "noble savage" attitude towards black

musicians as natural but untutored musicians - is unenthusiastic

about Coleman‘s harmolodics.

“I don't believe in harmolodics. What

happened to Ornette is what happened to a lot of black musicians of

African descent in America.

“The African's entire social and

cultural tradition is oral, but we're now in a society based on

European literary values. People in the literary tradition take you

less seriously when you can’t tell them what you’re doing in

concrete terms.

"Ornette was dismissed as

heretical because he couldn't explain it, so he made up that word

'harmolodic'. I just hear that direct lineage from Charlie Parker.

It's that simple.”

It's a lineage the Marsalis family are

consciously invoking, but not without humour as some suggest.

Branford laughs a lot at himself, just as Wynton did in Wellington

earlier in the year. He hoots about his nickname, Steeplone, which

brother Delfeayo mentions in his aggressively defensive cover notes

to Random Abstract.

"When I was with Art Blakey’s

band I grew my hair, and it grows in the middle like church steeple,

so they called me Steeple and that became Steeplone.”

He laughs again but has to go now. His

wife has “just walked in the door with about 25 cases of Coke and

beer for this party. I'd better go help."

A nice guy who knows what he's doing.

And like his father and brothers he's doing well.

Maybe it just runs in some families.

For a 2009 interview with Branford Marsalis see here.

post a comment