Steve Garden | | 9 min read

Note: there is no synopsis of The Tree of Life in the following article. It has been written with the assumption that those reading it have seen the film.

Opening quote: “Where were you when I laid the foundations of the Earth?” (Job 38:4, 7)

Image one: a formless warm light in a dark void.

Voiceover: “Brother. Mother. It was they who led me to your door.”

Image two: A young girl gazes in rapt wonder at the natural world.

Voiceover: “The nuns taught us there are two ways through life, the way of nature and the way of Grace. You have to choose which one to follow.”

So opens Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life, a film that moviegoers generally like even if they don’t fully comprehended it (judging by the online data). For some it is a near-transcendent experience, while others can only cringe.

The critics have been largely positive, some even going so far as to place it near the top of the cinematic canon! Others regard it as tosh: cliché-ridden, pretentious, faux-spiritual, faux-poetic, etc.

At the risk of seeming to have a bob each way, I empathise with both, although I certainly wouldn’t liken it to the Emperor’s new breeches. The film has more currency than that, even if its ultimate value belongs to its creator.

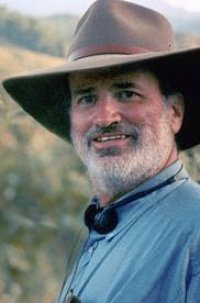

For many years Malick’s reputation rested on two impressive films: Badlands (1973, with Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek) and Days of Heaven (1978, acclaimed for its cinematic qualities, but marred by what some saw as a certain studied vanity in one or two of the performances).

He then vanished from view, purportedly to work on a screenplay about the origins of life (which, as it happens, served as the basis for The Tree of Life).

After 20 years in the wilderness, he returned in triumph with The Thin Red Line (1998), ostensibly a war film, but in essence a philosophical meditation on the dualistic nature of humankind: the battle between the material and the spiritual, and our capacity for selflessness, compassion and creativity vs. our propensity for unbridled hatred and destruction.

Few films open with an image as thematically eloquent as that of a crocodile slipping ominously into dark and murky waters, a powerfully evocative image of a natural killing machine that set the tone for the ruminations that were to follow.

In some respects, The Tree of Life is

for Terrence Malick what The Mirror was for Andrei Tarkovsky. Just as

Tarkovsky’s film expressed his philosophical ideas and reflected

his life and times, so does Malick’s, only in his mirror love

shines through all things, even the darkest of moments and regardless

of inevitable corruption.

In some respects, The Tree of Life is

for Terrence Malick what The Mirror was for Andrei Tarkovsky. Just as

Tarkovsky’s film expressed his philosophical ideas and reflected

his life and times, so does Malick’s, only in his mirror love

shines through all things, even the darkest of moments and regardless

of inevitable corruption.

Nothing is as compellingly knowable as the fact of death, and while it may have been inadvertent, the film offers an opportunity to ponder what love might be without it. More overtly, it juxtaposes American Christian spirituality on one hand, and American materialism (The American Way) on the other.

Malick suggests that these are up-for-grabs (if not irrevocably compromised) in these post-911 times.

The Tree of Life continues Malick’s enquiry into what it means to be human, but with an emphasis on what it means to be American. The Christian sensibility that informs all of its 140 reflective minutes testifies to Malick’s personal philosophy, making it ideally suited to those open to philosophical, metaphysical or theological discourse.

In many ways the first 20 minutes tell you all you need to know, thereafter the themes laid down in the opening are considered in more detail.

First and foremost, this is an American film. The themes may be universal, but their meaning and value are firmly located within an American context. It’s full of spiritual motifs, subtexts and transitions, from intimate moments to grand expressions of birth, death and rebirth, which collectively portray life as a journey hampered and enhanced in equal measure by the perpetual tussle between Nature and Grace, here embodied by Brad Pitt as ‘father/Nature’ and Jessica Chastain as ‘mother/Grace’.

The Tree of Life is a director’s piece. It’s not about acting, although it’s worth mentioning that on that level the children all-but steal the film. The adults acquit themselves with great skill and conviction, but they are essentially ciphers serving the thematic thrust of the film, used in much the same way that Stanley Kubrick would use actors from time to time. Notably The Tree of Life has been compared to 2001 A Space Odyssey.

The central narrative concerns the tensions between a domineering father (played by Brad Pitt) and his sons, particularly the eldest boy, Jack. Sean Penn plays Jack as a middle-aged man suffering an existential crisis: overwhelmed by feelings of guilt and worthlessness, and the need for reassurance, forgiveness and reconciliation.

The father’s overbearing approach leads to resentment, unhappiness and dysfunctional behaviour in his children. His authoritarianism stems, in part, from his personal failings and disappointments, but also a genuine desire to prepare his family for the dog-eat-dog world they will discover as young adults.

As his world collapses, he struggles with his conscience, self-esteem, and what remains of his faith. As in numerous films before it, this aspect of The Tree of Life depicts the age-old necessity for successive generations to reconcile the broken legacy they inherit. But there is political subtext to be discerned here too.

Malick doesn’t try to pretend that

the questions and tensions he grapples with are anything new –

indeed, they are as old as Adam – but how we deal with them, he

implies, is everything. Perhaps the biggest question he asks is, if

God exists (regardless of how one rationalises such a concept), what

are we to Him (or It)?

Malick doesn’t try to pretend that

the questions and tensions he grapples with are anything new –

indeed, they are as old as Adam – but how we deal with them, he

implies, is everything. Perhaps the biggest question he asks is, if

God exists (regardless of how one rationalises such a concept), what

are we to Him (or It)?

Hence the opening quote (one of the Deity’s great rhetorical questions), intended to remind humankind of their place in the scheme of things. One thing that most likely irritates those who dislike the film is that its director assumes to know the answers to his own questions, which is dangerous for a maker of this kind of film because he risks what could be a rhetorical experience for his audience.

Whether or not the prehistory section (a depiction of the origins of life, and a brief but thematically pertinent scene with dinosaurs) was necessary, The Tree of Life is one of the bravest American films of recent years, if only for holding a mirror up to America, offering an invitation to the nation to reflect on where it has been, where it’s at, and where it’s going.

The underlying tone is one of regret, loss, shame, emptiness and disillusion, yet it is far from a hopeless vision, even if (as the final section suggests) ultimate Reconciliation and Wholeness is the reserve of the afterlife – the “real” Land of The Free and Hope for The Hopeless, where the Promises of God will finally come to fruition.

The implication is that the Hope of the faithful is to live in the knowledge of the Grace to come, as if Oneness were Reality now, wherein lies the transformative power of Faith, the Courage to weather ‘the rain that falls on the just and the unjust’, and the Wisdom to reconcile Love in a world given to Enmity.

Yes – it’s all rather heady, capital-letter stuff!

Some might find the Christian intimacy

of the film hard to deal with, and even those open to it might

struggle with Malick’s poetic-philosophic abstractions. At the

screening I attended the audience barely contained its scorn at the

‘formation of life’ sequence, which the dinosaurs only made

worse. Thankfully they didn’t have to wait long before Brad and

something resembling a coherent narrative returned to settle things

down.

Some might find the Christian intimacy

of the film hard to deal with, and even those open to it might

struggle with Malick’s poetic-philosophic abstractions. At the

screening I attended the audience barely contained its scorn at the

‘formation of life’ sequence, which the dinosaurs only made

worse. Thankfully they didn’t have to wait long before Brad and

something resembling a coherent narrative returned to settle things

down.

“Grace doesn’t try to please itself,” Malick tells us, going on to show how it suffers indignities and injustices because, by its very Purity, it is compelled to do so. Nature, on the other hand, “only wants to please itself”.

The Tree of Life may be Malick’s Mirror, but he is no Tarkovsky. It may depict the Higher Calling of Grace, but the film is more aligned with Nature in that it essentially seeks to please. One senses that we are expected to be impressed by the work, to leave the theatre in awe of its mysteries and profundity. But despite the metaphysics, the film lacks the requisite rigour and depth to warrant inclusion in the cinematic canon.

All it takes is for something like Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master to come along to reveal how extraordinary cinema can be. Nevertheless, I’m compelled to defend The Tree of Life, not for what it perhaps aspires to be, but for what it is.

It would be easy to say, as some have, that the film is an attempt to make a 2001, A Space Odyssey for the new millennium, and there could be some truth in that. Malick’s aspiration is nothing if not spelled out in capital letters. If the images aren’t enough to signal big themes and grand intentions, the music most certainly alerts us to an ambition to approximate the Finger Print of the Universe.

You either go with this or you don’t – or can’t. I did. I gave the filmmaker the benefit of the doubt. One must let the filmmaker speak, especially one with such singular and uncompromising purpose.

The dinosaur sequence is a case in point.

I wonder how many people realised (those who weren’t busy scoffing)

that the intention of this section is to convey the birth of empathy

in a brutal, survivalist world. Rather than kill the smaller and

vulnerable dinosaur, the larger creature hesitates, pulls back, and

goes on its way, but not before stopping to register something new in

the air, something new in its soul in fact – not that it is fully

aware of that yet.

The dinosaur sequence is a case in point.

I wonder how many people realised (those who weren’t busy scoffing)

that the intention of this section is to convey the birth of empathy

in a brutal, survivalist world. Rather than kill the smaller and

vulnerable dinosaur, the larger creature hesitates, pulls back, and

goes on its way, but not before stopping to register something new in

the air, something new in its soul in fact – not that it is fully

aware of that yet.

It is the inverse to the ‘Dawn of Man’ sequence in Kubrick’s 2001, where the black monolith signals or inspires an advance in human progression, namely to fashion a weapon from a bone which famously match-cuts to a space station some millions of years later. In Malick’s version the advance is Inexplicable – and entirely spiritual.

God exists in Malick’s mirror, and Creation is an evolutionary process designed to affirm Love, against the odds. The Tree of Life suggests that without compassion and empathy we are little more than dinosaurs bound to go the way of all flesh. It’s through our willingness to listen to the near-inaudible Whisper of Grace that we rise above (if only sporadically in our otherwise comfortably preoccupied lives) our inherently brutal nature: the dinosaur within.

Malick implies that it’s all about coming to terms with ‘Father’: the legacy our natural father (our upbringing, conditioning, aspirations, fears, etc), and the Father that is existence itself, that which perpetually calls us to reconcile ourselves with ourselves. In this sense, Malick addresses the personal and the political, wherein reconciliation is a socio-political necessity. America, he suggests, must reconcile itself with itself. The Tree of Life is, therefore, a film about growing up – choosing to look into the mirror and confront what’s there.

While he skirts perilously close to

Hallmark sentiment at times, particularly the recurring images of

sunlight through trees and the ever-wafting fluidity of the camera

(suggesting an Omniscient presence), Malick’s visual language

abounds with moments as inconsequential and as profoundly mysterious

as a leaf in the wind, where even the most innocuous image carries

the suggestion of deeper metaphoric substance.

While he skirts perilously close to

Hallmark sentiment at times, particularly the recurring images of

sunlight through trees and the ever-wafting fluidity of the camera

(suggesting an Omniscient presence), Malick’s visual language

abounds with moments as inconsequential and as profoundly mysterious

as a leaf in the wind, where even the most innocuous image carries

the suggestion of deeper metaphoric substance.

The problem is that Malick (right) is very fond of his visual motifs, which he too often milks for their implicit wonder. The result is a film that teeters on the edge of visual cliché. The ending may be a white, middleclass, protestant vision of Eternal Oneness, but the point is clear. The Tree of Life is a testament of faith, a film about striving to overcome brokenness and moving to a place of acceptance, humility, forgiveness, reconciliation and growth.

It may not be the best film ever made, but it’s certainly a sincere and searching one, which might be why those who value it regard it so highly – because they recognise and are affected by its central purpose.

Those who dismiss it for its supposed pretentions and high-mindedness are unlikely to tolerate its central message: that life offers the potential to transcend nature and engage with something resembling Grace.

Steve Garden is an award-winning record

producer in Auckland for Rattle Records whose albums have featured

prominently at Elsewhere. For more on the full Rattle catalogue see

here. You will be impressed. Steve has previously contributed to Other Voices Other Rooms here.

Other Voices Other Rooms is an opportunity for Elsewhere readers to contribute their ideas, passions, interests and opinions about whatever takes their fancy. Elsewhere welcomes travel stories, think pieces, essays about readers' research or hobbies etc etc. Nail it in 1000 words of fewer and contact graham.reid@elsewhere.co.nz.

See here for previous contributors' work. It is wide-ranging.

Relic - Feb 12, 2013

Engaging, but main section desiccated like the later scenes in “Brokeback Mountain” and kid laden too.

Savepost a comment