Graham Reid | | 2 min read

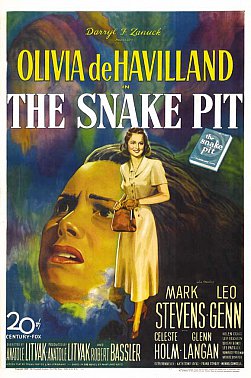

Much of the hoopla surrounding Anatole Litvak’s 1948 drama The Snake Pit focused on the treatment of its subject matter.

It was one of Hollywood’s first attempts to tackle mental illness sympathetically, backed by extensive background research and a sincere performance from lead actress Olivia de Havilland as a young woman institutionalized after a nervous breakdown.

And the movie was big news, praised as a realistic groundbreaking drama and a critical and commercial success, picking up Oscar nominations, awards from the Committee of American Psychologists and landing in the top five highest grossing movies of the year.

But that was a long time ago and much of the apparent realism and topical shock value doesn’t seem like such a big deal now.

Nevertheless it’s still a messy engaging drama.

Set in the overcrowded women’s wards of a state mental institution, we follow newly wedded writer Virginia Cunningham (de Havilland) through the long process of reclaiming her sanity battling grim hospital conditions, vindictive nurses and her own dysfunctional mind.

Fortunately, Virginia is singled out for special treatment by Doctor Kik played by the silver tongued Leo Genn. Working against standard hospital norms Kik advocates individual patient care and practices a Hollywood shorthand version of Freudian psychoanalysis that’s a little too simple to make sense.

But it does make sense to Virginia as she uncovers the origins of her illness buried deep in her subconscious.

The symptoms of Virginia’s buried trauma manifest in what Kik terms as Virginia’s rejection of her husband’s love, Virginia forgets her him, their marital status and brushes off his attempts at affection.

Which sets up the question: will Virginia come to her senses and accept her husband? Although 60-plus years since the movie was made we could interrupt the question a little differently and wonder why it is so important that Virginia’s recovery hinges on the acceptance of her husband.

Couldn’t she just get better and go it alone?

This is a film that doesn’t have a singular identity, a socially conscious drama and a melodramatic romance, employing several different methods to get the story across. The details of daily life in the institution; day rooms filled with noisy patients marshaled by battle axe nurses, the cramped makeshift night dorms and the bad food, are filmed objectively, without too much fuss.

By contrast we also get highly emotive scenes shot from Virginia’s point of view, dramatically ramped up with shrieks of music. But things get really weird with two surreal scenes that attempt to convey images from Virginia’s mind, which in retrospect, feel like strange inserts from another movie.

Although, there is no denying this was a well-intentioned movie that tried to portray the ticks and nuances of mental illness correctly.

Litvak, de Havilland and writers Frank Partos and Millen Brand spent a three month preproduction period consulting psychiatrists and taking observational trips to institutions. And de Havilland for her part drabbed-down in holey dresses and stockings, forlorn hair and no discernible make up. And detailed her performance with fidgety hands and an expressive face, and she conveyed

Virginia’s fleeting emotions with a voice that goes from a girlish chirp to an assertive growl within the space of a sentence.

De Havilland played Virginia as a sweet endearing woman, whose mental fragility doesn’t detract from her likable nature.

And regardless of what did or didn’t work in this drama, Virginia is still a character, who you care enough about to stick around till the end of the movie, to see how she fares.

Sarah Jane Rowland is a writer who lives in Auckland, works in a library and her not-so secret passion is film. She is well read and well viewed. Her previous contributions to Other Voices Others Rooms are here.

Other Voices Other Rooms is an opportunity for Elsewhere readers to contribute their ideas, passions, interests and opinions about whatever takes their fancy. Elsewhere welcomes travel stories, think pieces, essays about readers' research or hobbies etc etc. Nail it in 1000 words of fewer and contact graham.reid@elsewhere.co.nz.

See here for previous contributors' work.

post a comment