Andrew Dawson | | 9 min read

The Members: The Sound of the Suburbs

Of all modern musical genres, it's undoubtedly punk music that exemplifies Said’s thesis that texts (in the broadest definition) are produced by and engage with the historical, political and aesthetic concerns of the world around them.

Early punk expressed, above all, the socio-political concerns of those who felt excluded from the mainstream discourse of late Seventies Britain. Yet, while it is clear that “punk is political”, it would be a mistake to see the genre as a coherent ideological critique of mainstream values, proposing a clear alternative for society.

The myth of punk as a proletarian, left-anarchist movement obscures the fact that the main figures of the movement were a mix of working-class youth and middle-class art school types who espoused a variety of views (often vaguely) in critique of the British political and musical establishment.

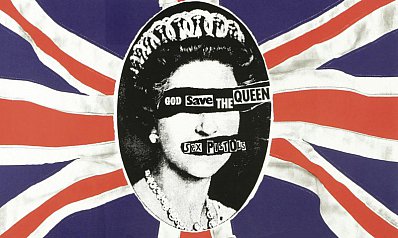

An exploration of the music and lyrics of three early punk bands – the Sex Pistols, the Clash and the Damned – shows this broad range of agendas, yet also reveals the unifying program of punk as an anti-establishment cri de coeur that embodied an irreverent, nihilist, do-it-yourself youth perspective.

Punk articulated, and in

some sense created, an oppositional attitude toward mainstream

society which captured the voices of its generation, and paved the

way for a new approach to music. The genre was able to do so

precisely because of its committed (though multivalent) engagement

with the world in which it emerged.

Punk articulated, and in

some sense created, an oppositional attitude toward mainstream

society which captured the voices of its generation, and paved the

way for a new approach to music. The genre was able to do so

precisely because of its committed (though multivalent) engagement

with the world in which it emerged.

The historical world into which British punk arrived was, undoubtedly, a key factor in its accelerated rise to prominence. British music had become disconnected from the world of youth, and failed to articulate key concerns in the public consciousness.

David Simonelli, an associate professor in History at Youngstown State University noted that: “Teens were gloomy and fatalistic. It seemed there was little hope of a future in 1975 if you were young and working class, and there was little question that the rock music they listened to did nothing to reflect their plight … to a core group of working-class youth, the economic privations of 1975 demanded that their music reflect their values more exclusively”.

Punk emerged as a response to this demand, and capitalised on the dissatisfaction of youth by providing them with a voice in an angry, insurrectionary music that uses history to articulate a youth agenda.

This

agenda can be seen in one of the early Sex Pistols hits, Holidays In

The Sun ('77), where Johnny Rotten/John Lydon sings “I wanna see

some history” and draws on the image of “the Berlin Wall” to

explore youth concerns. Lydon’s lyrics draw an analogy between “the

Berlin Wall” (a symbol of communist oppression) and the prevailing

sense of economic entrapment felt by working-class youth within

Britain, who could never afford “a holiday in the sun” even if

they wanted to. The music of the song also makes use of the loud

opening guitar riff of the Jam’s In the City ('77), a song that

critiques police brutality in the 70’s.

This

agenda can be seen in one of the early Sex Pistols hits, Holidays In

The Sun ('77), where Johnny Rotten/John Lydon sings “I wanna see

some history” and draws on the image of “the Berlin Wall” to

explore youth concerns. Lydon’s lyrics draw an analogy between “the

Berlin Wall” (a symbol of communist oppression) and the prevailing

sense of economic entrapment felt by working-class youth within

Britain, who could never afford “a holiday in the sun” even if

they wanted to. The music of the song also makes use of the loud

opening guitar riff of the Jam’s In the City ('77), a song that

critiques police brutality in the 70’s.

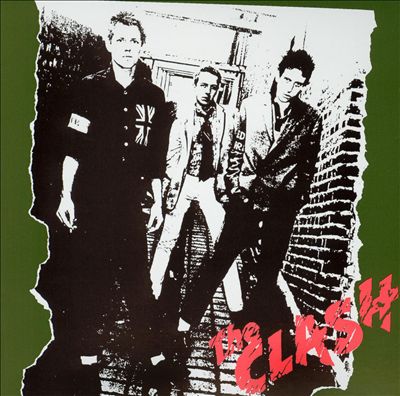

The

Clash, too, appropriate history by drawing on reggae’s critique of

police brutality in their cover of Junior Murvin’s Police and

Thieves ('77). The lyrics of this song juxtapose police and

terrorists who were both “Scaring the nation with their guns and

ammunition”.

The

Clash, too, appropriate history by drawing on reggae’s critique of

police brutality in their cover of Junior Murvin’s Police and

Thieves ('77). The lyrics of this song juxtapose police and

terrorists who were both “Scaring the nation with their guns and

ammunition”.

The Clash update this Jamaican rebel anthem, making reference to the train bombings by the IRA: “The station is bombed/Get out get out get out you people/If you don't wanna get blown up.”

By doing this, the Clash import a black resistance paradigm into the rhetoric of British youth, a program of appropriation they will develop in other songs.

In contrast to both of these groups, the Damned were less directly engaged with history, but nevertheless represented the attitude of youth in songs such as You Take My Money ('77). The lyrics of the song are simple, repeating the title, but the line “You take my money all seven pounds” reveals working-class youth poverty. The intended addressee is also suitably ambiguous; it could be a person, family, or even society that takes the money away, thus allowing the song to represent a wide variety of youth concerns at the personal and societal level.

This

multivalence of youth perspectives is also evident in early punk

musicians’ dual class backgrounds. While the vast majority of punk

bands constructed themselves around the mythos of working-class

unemployed youth, not every major figure was from this background in

reality.

This

multivalence of youth perspectives is also evident in early punk

musicians’ dual class backgrounds. While the vast majority of punk

bands constructed themselves around the mythos of working-class

unemployed youth, not every major figure was from this background in

reality.

These differences led to varied foci both between and within the bands towards history, politics and their approach to ‘the future’. Yet, as Bernie Rhodes, the Clash's manager said, “You need the mix of working-class roughage with middle-class kids to make a group work”

While the first wave of punk was ultimately blown apart, partly because of this admixture of class perspectives, it was undoubtedly also the reason punk was able to gain such a large audience so rapidly in its first, short, incarnation.

The Sex Pistols are the best example of this dual perspective, arguably the most influential punk band precisely because “they married … the bitter and bilious anger of Johnny Rotten and Steve Jones with the intellectual art school rebellion of Glen Matlock and manager Malcolm McLaren,” according to Simonelli.

The messages of many of the Sex Pistols’ songs are peppered with Situationist discourse with its critique of “fascist regimes” of capitalism and the promotion of “anarchy”, even though the group was not necessarily as ideological as their lyrics would propose. Nevertheless, the key factor to the Sex Pistols success was the fact that these messages were mediated through the working-class lens of Lydon, who was not ultimately concerned with constructing an ideological alternative, but rather wanted to tell youth to “get off your arse” and engage with the world.

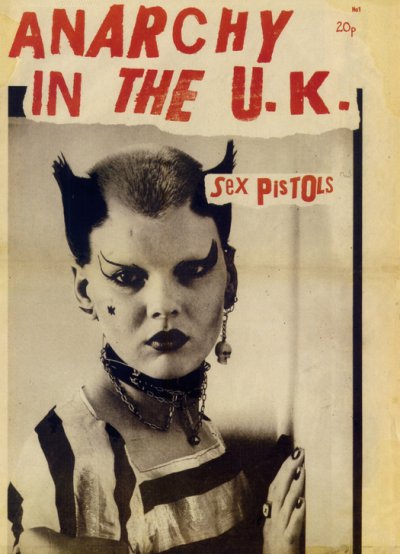

Anarchy

in the U.K. ('77) is an excellent example of Lydon’s agenda in

action. In the song, he uses the discourse of “anarchy”, but it

is not in an attempt to provide any constructive ideology, but rather

“to destroy” the structures which suffocate him. In the famous

line “don’t know what I want, but I know how to get it,” Lydon

does not attempt to answer the problems of working-class youth, but

uses music to express a visceral angst with the current state of

affairs that tapped into the prevailing youth attitudes of the time.

Anarchy

in the U.K. ('77) is an excellent example of Lydon’s agenda in

action. In the song, he uses the discourse of “anarchy”, but it

is not in an attempt to provide any constructive ideology, but rather

“to destroy” the structures which suffocate him. In the famous

line “don’t know what I want, but I know how to get it,” Lydon

does not attempt to answer the problems of working-class youth, but

uses music to express a visceral angst with the current state of

affairs that tapped into the prevailing youth attitudes of the time.

By contrast, the Clash present a more coherent version of “anarchy” grounded in the Black tradition of resistance, yet one which ultimately reveals their predominantly middle-class roots.

The fact that “Mick Jones and Paul Simonon [and Joe Strummer] of the Clash were […] ‘upwardly-mobile art students’" (in the words of writer Paul Fryer) provides an explanation for the underlying middle-class “anarchism” proposed by the group. Continuing the program of appropriating Black resistance culture into their songs, White Riot ('77) is a song that expresses angst at the complacency of British society, yet the song belies any working-class pretensions.

The lyrics “white people go to school/where they teach you how to be thick” is a clear critique of middle-class complacency; the source of political apathy is not disillusionment (as with Rotten’s lyrics), but rather interpellation into the middle-class value system.

They continue this critique in songs such as Career Opportunities ('77) which sing about society’s demand that youth “take anything they’d got” from largely middle class careers: “a cop”, “ambulance man”, “civil service”. The very use of the word “career” as opposed to job shows a fundamentally middle-class attitude. The statement in White Riot that “All the power's in the hands/Of people rich enough to buy it” shows a more clearly left-leaning politics than Rotten’s “I wanna destroy”.

Paradoxically then, it is the educated voice that appropriates working-class/minority sentiments to refashion the ideals of the middle-class, in an attempt to take down perceived power structures.

While the Sex Pistols and the Clash outline divergent approaches to “anarchy”, the Damned, once again, stand in stark contrast to both, “derided … for lacking any political intent in their music”, says Simonelli.

It is difficult to find the background of many of the members, except that Rat Scabies “with true hippie fervour, rejected his wealthy background during adolescence,” writes Fryer in Punk and the New Wave of British Rock: Working Class Heroes and Art School Attitudes.

The fact that further details about the members’ backgrounds are not easily available is consistent with the group’s lack of concern to position themselves as a political voice for working-class youth. In Politics ('77) the group proclaims it desires “No rules, no laws, no regulations,” but lest the listener think they are advocating anarchy, Dave Vanian emphatically states “Give me fun not anarchy.”

While it would be easy to set aside the group as the party boys of punk, they were in fact astute observers of the inner politics of the musical world. Politics offers a scathing critique of the “Fascist manager’s dreams” of figures like McLaren, who used politics to “sell clothes” and capitalised on a “politically fashionable scene”.

Rather

than trying to articulate a vague “anarchist” philosophy, the

Damned focused instead on giving youth a raw musical style that

articulated their dissatisfaction with society in general. The Damned

were thus, arguably, the most connected with the heart of punk’s

appeal. It was not ultimately revolutionary politics that young

people wanted – in a concert it would have been hard to hear the

lyrics – instead, “the working-class street punk saw the music

and the rebellion it represented as primarily fun instead of

revolutionary,” according to Simonelli. The music was, above all,

about giving youth a way to express feelings of angst against

society, not in service of a political agenda, but as a form of

individual and collective self-expression.

Rather

than trying to articulate a vague “anarchist” philosophy, the

Damned focused instead on giving youth a raw musical style that

articulated their dissatisfaction with society in general. The Damned

were thus, arguably, the most connected with the heart of punk’s

appeal. It was not ultimately revolutionary politics that young

people wanted – in a concert it would have been hard to hear the

lyrics – instead, “the working-class street punk saw the music

and the rebellion it represented as primarily fun instead of

revolutionary,” according to Simonelli. The music was, above all,

about giving youth a way to express feelings of angst against

society, not in service of a political agenda, but as a form of

individual and collective self-expression.

Turning to the genre as a whole then, it is clear that (in spite of all the political pretensions of groups like the Sex Pistols and the Clash) punk was not so much an ideology as an aesthetic attitude towards life. In this respect, the bands of early punk were clearly engaged in an aesthetic project that gave disaffected youth an identity; with clothes, an irreverence toward society and a Do-It-Yourself harsh musical style that embraced “amateur” as a positive moniker.

This does not mean that punk was an escape from politics and life; it was a construction and articulation of an attitude that offered youth of the period a way to engage with society, by creating a space in which their multifarious views could be voiced. All three bands were key in constructing such an attitude, even if some pretended to have more ideological motivations that obscured this primarily aesthetic project.

The power of punk lay not in propounding vague ideological agendas, but in harnessing the subjective voice and attitudes of youth to create an aesthetic politics that challenged dominant sensibilities in music and society.

The genre paved the way for future artists who would explore a broad range of musical styles and perspectives in the post-punk era, even if early punk had to immolate itself in the pursuit of this radical aesthetic revolution.

Andrew Dawson's interests range from ragas to r'n'b, and he has a secret passion for medieval literature and Derek Walcott's poetry. He enjoys writing, teaching, and travelling . . . between his studies in English and Music at the University of Auckland. His previous entry at Elsewhere was a consideration of Michael Houstoun's interpretations of Beethoven's piano sonatas.

Other Voices Other Rooms is an opportunity for Elsewhere readers to contribute their ideas, passions, interests and opinions about whatever takes their fancy. Elsewhere welcomes travel stories, think pieces, essays about readers' research or hobbies etc etc. Nail it in 1000 words of fewer and contact graham.reid@elsewhere.co.nz.

See here for previous contributors' work. It is wide-ranging.

post a comment