Graham Reid | | 14 min read

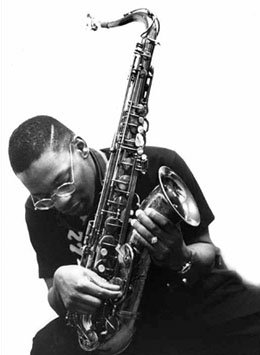

If musical talent is in the genes then Ravi Coltrane was twice blessed: his father was the legendary tenor saxophonist John Coltrane whose spiritual and searching bebop redefined jazz in the late 50s and 60s; and his mother was the gifted pianist/composer Alice who played in her husband’s group and whose own creative contributions have perhaps been unfairly overshadowed by his achievements.

Born two years before his father’s death in ‘67 and named after the Indian sitar master Ravi Shankar, tenor and soprano player Ravi Coltrane inherited the musical gifts of his parents, but has made his own way working with innovative musicians such as Steve Coleman and Geri Allen, legends such as Pharoah Sanders and Herbie Hancock, and latterly helming his own quartet.

But growing up you have to wonder if there was ever a time when he, like most kids, rebelled. Did he ever say, “Mum, I wanna be an accountant?”

From his New York home the quietly spoken and good humoured Coltrane laughs loudly: “Fortunately it wasn’t necessary for me to rebel against music because it was never pushed on me. But there was a time I thought about going to film school. I was really into photography and the technical aspects of film making.”

In 1986 he attended the California Institute of Arts to study music, yet even at then didn’t expect he would leave four years later as a jazz musician. He went as a listener curious to see if he could play improvised music. There he was inspired by the great bassist/composer Charlie Haden.

After CalArts Coltrane made his way back to New York, played with the late drummer Elvin Jones (“I wasn’t really ready, I had just got out of school. I was shy and awkward”) and in 2002, after playing on dozens of sessions and with a roster of great musicians, he founded his own quartet. Their most recent album In Flux suggests this Coltrane has found his own voice.

My understanding your quartet has just come back from Europe.

Yeah, we were there for two weeks, we were doing concerts and club dates. We go usually once a year in the Fall. Sometimes I’ll do a special project in the summer but I’ve been leading bands in Europe since about 99.

After New Zealand you are going back to India again?

How did that get out? That is strange because I asked my manager to look into a possible flight instead of back to the States to go through India, so I have no idea how anyone else could know that. But at the moment my ticket is still back to New York.

You have been a couple times to India?

Only the once, in 2005. I would like to have more opportunity to play there. I went as part of a large group of American musicians [which included Al Jarreau, Earl Klugh, George Duke] who were going as a kind of State Department tour [to promote HIV/Aids awareness] but I haven’t travelled there with my own band. But this trip would be more of a personal trip.

You have very stable quartet now.

Yeah, since about 2002. That was part of the plan for me, I always wanted to have the ‘working band’ that grew together like a nice steady collective. That goes a long way to giving you something you can’t otherwise get.

You can have the greatest musicians alive rehearse once together and go make a record and maybe some great things will happen, but maybe great things won’t happen. Sometimes they don’t connect no matter how great they are.

The thing you can’t manufacture is a relationship when you know someone so well that you can finish their sentences, musically speaking.

I always admired those kinds of bands throughout history and can see how this natural progression exists in certain groups. Look at any of Miles Davis’ groups, the John Coltrane Quartet of course. You can see how one element is pushing another. These guys surrounded themselves with themselves: Bird played with Monk, Monk played with Sonny Rollins, Sonny Rollins played Miles, Miles played with Bird, Bird played with Diz, John Coltrane played with Miles and Monk . . .

They were feeding off each other and building each other up in the process.

That has always been an exciting idea for me, and we have choices now and we can find something that is special and just keep doing it.

Year after year we get closer as friends and the music takes another shape so it is, ‘we know this is going to happen so let’s just play it’. (laughs)

On In Flux I hear a confidence in the number of musical idioms that go on.

Yes, a lot of what we played on that record, a lot of the ideas and rhythmic things, we have been playing on gigs for years and we could easily apply them to specific things. Something that could have been a stumbling block in the studio we had already got over so we could deal with the other elements in the music.

Let me ask you about your background: you grew up in a house full of music and you were presumably influenced not only by your father’s music but also your mother’s. But was there any point where you rebelled and said, ‘No Mum, I want to be an accountant’? Was there a point where you wanted to do something other than music?

(Laughs) Of course, but it wasn’t based on rebellion. Fortunately it wasn’t necessary for me to rebel against music because it was never pushed on me, it was never propped like it was the thing I had to do., My mother didn’t do that to me, she allowed me to be myself and follow the interests I had as a young person.

There was a time I thought about going to film school and I was really into photography and the technical aspects of film making.

But I played the clarinet in the high school marching band, that was my choice. My mother was always very supportive of anything her kids wanted to do.

I wasn’t listening to a lot of jazz growing up. I heard it and the music was there and it was music I liked. I dug it and appreciated it, but it wasn’t something I was following. I was listening to the music that everyone else was listening to, I listened to the radio and tons of r’n’b and funk music and rock, and some classical music.

My mother played classical music in the house so my whole life I listened to certain pieces of Stravinsky, Chopin, Rachmaninoff, Dvorak . . . Those were her favourites so they became mine too (laughs)

But you were listening to Parliament and Funkadelic too?

Yeah I was really into Stevie Wonder, James Brown, Earth Wind and Fire, the Beatles, Steely Dan . . . I was a big Donald Fagen fan. That was what was happening for me and the jazz thing didn’t come until much later.

My older brother [John Jnr] had passed away in 82 and everything got very skewed for me direction-wise, it was like the rug was pulled out and wherever you think you were going you are now reeling and tumbling around.

So I spent a lot of time, maybe three or four years, just working odd jobs to pass the time -- but during that period I started listening more specifically and directly to my father’s music and I started to recognise and hear in the music things that I had never hear before. The music was speaking to me in a way I hadn’t heard before. So it was only then that I wanted to jump on the wagon, because it was starting to make sense and call me.

The whole process, fortunately, was very organic. It was never, ‘Oh, I feel like I need to do this, this is what they expect’ or ‘I should do this because my name is Coltrane‘. (laughs)

Was there -- actually I can answer this probably but I’m going to allow you to answer for yourself -- was there a moment where you woke up to the fact you were the son of two great musicians?

(Laughs) No, when you are in the middle of it and it is a daily part of your existence, to the time you are old enough to realise it, it is not such a thought process that comes to you. You accept it as part of your reality.

When you are in thick of it you can look at it and go ‘wow’. But who you are is who you are, everything you are exposed to as a young person from culture or family history is all kind of included. You don’t step back from it and go, “hey, I’m a Coltrane’

I’m extremely proud and aware of who they both were, and I’m as appreciative and respectful of their work as anybody. I have an admiration and love for their work, as anyone who loves music and the creative spirit and drive would be. So I can sit back and go ‘this record is unbelievable’ and can separate myself from it in that sense.

If I never got into making music I could still respect it and like it. And I did that for a good part of my life, but the point where I could hear the music speak to me opened up a major door.

When you went to California Institute of Arts, was that where you met Steve Coleman?

I met Steve around 92 in New York. I was at CalArts between 86 and 90 and went there to learn how to improvise. I had very little experience in trying to play jazz, playing over changes and so on. I didn’t do that, I’d played clarinet in the marching band (laughs)

I had obviously heard the music but when I went to CalArts I went there cold, it was brand new experiment. I didn’t say to myself that I would leave that institution in four years as a jazz musician.

I went as experiment because I went as a listener and wanted to see if playing it was going to be something I could be interested in.

Charlie Haden was one of your tutors?

Yes, he was and still is the artistic director of the programme. It was through my mother’s encouragement that I ended up going to CalArts because she said Charlie was there so that’s where I should go when I finally told her I wanted to study music.

Had you known him on any personal level beforehand through your mother?

As much as I could know any musicians who were working with my mom. I was a kid and I’d be hanging out in the studio and being shushed and told ‘it’s time to be quiet now‘. I’d be watching musicians play but trying to goof off and have fun.

I was accustomed to seeing certain people around the house and in the studio.

He was quite some influence on you I understand?

Yeah, I love Charlie and he is one of my all-time favourite guys. I was just talking with my manager about him for a project. Charlie is sometimes hard to get because he’s in LA and we’re here, and my manger was thinking of time and deadlines so mentioned another bass player who was fine. But for this thing it has to be Charlie.

Charlie has something in his music and sound that no one else has, there is a deep honesty in his playing.

When I was growing up my mother worked incredibly hard too, but you are kid riding your bike so you don’t notice it, it’s just your mom. She was cool and never said ‘look I’m doing this and it’s really serious’ she would just say to go in another room and play with my toys.

Charlie had a very different experience than my mother in their respective heydays, so hearing him speak about music . . . I’d never heard anyone speak about music like that before: the life of musician, the hardness of the life, the difficulty of it, how much you have to love what you are doing for it to really work.

There was a commitment he’d made to this music despite everything he’d been through and was going through. His life in the 50s was very rough. But he was so honest about it, there was no embarrassment, no him trying to get you think this or feel that way.

He was just, ‘I’m relaying this to you, this was part of the scene and this affected the music’. It really made you think about things.

One of the things he said was that every time you play you should play like it was the last time you would ever play.

It sounds like a nice slogan or line to put out there, but as a 20-year old student I’m there in a classroom of kids -- but when he picks up his bass he is playing as if this was the last time.

That was heavy to see for a young person, it really focuses you on what the important things are in life.

He is one of my favourite musicians and like most people I came to him through Ornette Coleman but have followed his career avidly. Tell me about Steve Coleman because I’ve just mentioned Ornette whose harmolodic theory bewilders me as I suspect it does most people. But Steve has his own theory, M-Base, which seems like a philosophical and cultural idea as much as a style.

Steve came up with a name and was playing the music he wanted to play and suddenly here was this M-Base sound and style. I think it was something that amused him and I think it still does. But yes, there was a collective of people in the same place at the same time into the same things and they formed bands.

Steve’s ideas are pretty intricate and intense, and they are real. He’s not bullshitting or just trying to impress you. It’s not a competition for him but he’s really into knowledge. He reads like madman, he doesn’t have furniture in his house he has books. He’s one those characters. (laughs)

He’s unconventional and it might be too much for some people but it informs everything he does. His appetite for information regarding all forms of music is what he is into, and I had never been around anybody like him. You didn’t know what you were going to get with him, it was so intense and non-stop.

I met him in the Blue Note and we traded numbers and about a week later he called me. The first conversation we had lasted maybe four hours. It might have been longer and here was a guy I didn’t know at all calling and I think we’ll maybe shoot the breeze a little bit. But four hours? The thing was, it wasn’t boring.

And you went back for more?

(Laughs) Now I can’t really pick up the phone when Steve calls. I’ve got kids and this record company and a career, I can’t really speak on the phone with him because it would always be at least two hours because he’ll start on Charlie Parker then go to African music and John Coltrane . . .

It’s real and he has a lot of ideas and in the mid 90s that really affected me deeply when I was hanging with him and learning his music and checking out the music he was into. It helped me a great deal.

I was working with Elvin Jones at the time and he was an influence in way that was huge, but what I was getting from Steve was also huge in a very different direction, in a very open way.

Working with Elvin was my first real gig and I wasn’t really ready to play with anybody because I had just got out of school. I was shy and closed in and awkward, and it was very heavy for me. But I started hanging around with some different guys who were thinking about the performance of music and it was starting to open me up, and Steve was one of those guys.

You have played with so many people now there must have come a point where you realised that you had found your own musical voice.

Is that a question? (laughs)

Yes, that’s a question.

Ahh, I don’t know about that. I’m thrilled I’ve been able to work and play with a lot of people that I have respected for a long time. I want to continue playing and developing and getting better as a musician, composer and conceptualist. I think it is a long process that doesn’t end until you stop playing. A long process of development.

You can manufacture a sound and a lot of people do that all the time, some very talented people do it quite often.

People say, ‘this guy can really play and sounds like so-an-so’. Well, I don’t want to sound like so-and-so. No matter how much I love that person and may be influenced by him, I don’t want to sound just like him.

It defeats the purpose of being of being an improvising jazz musician because the guys that I admire didn’t sound like the guys that they admired.

So the lesson to learn from these guys isn’t just what comes out of their instruments, but the path they took and how they got to that place where they had a personal and innovative sound. That has always been a part of my thinking.

I made a choice that I didn’t want to sound just like the guys I have studied, but that doesn’t mean you are going to go on and do something innovative. It just means that you are going to go on and have a personal sound and you sound like you.

It’s a tricky thing because we don’t want to get too far away from the fuel -- which is the reason why we do this in the first place -- but the goal is to sound like yourself, and that was the goal for the guys that we follow and admire despite the fact that they had all the history before them down cold.

post a comment