Graham Reid | | 4 min read

I grew up with the sea. My dad was a radio operator in the British Merchant Navy in World War II and had a passion for the ocean.

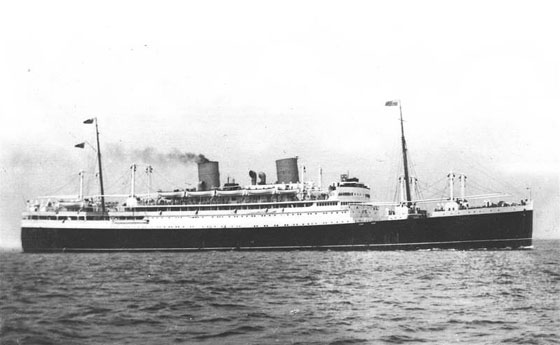

He gravitated to the sea at any opportunity; we sailed back and forth between Britain and New Zealand on the Rangitiki and my dad was friends with dozens of people from “the Rangi boats” in the New Zealand Shipping Company (Rangitiki, Rangitane and Rangitata).

Every time their ship was in they'd come to our house.

Later in life he got a job with a shipping company which seemed to entail taking paperwork on board ships and drinking with the captain.

At our house over the fireplace was a very large print of a wind-blasted ocean and breaking waves under heavy clouds.

At our house over the fireplace was a very large print of a wind-blasted ocean and breaking waves under heavy clouds.

Stories of the sea were part of my childhood: Treasure Island, pirates and buccaneers, most especially Robinson Crusoe. I've written elsewhere (at Elsewhere here) about how important and formative that book was when I was growing up, and then even later in life.

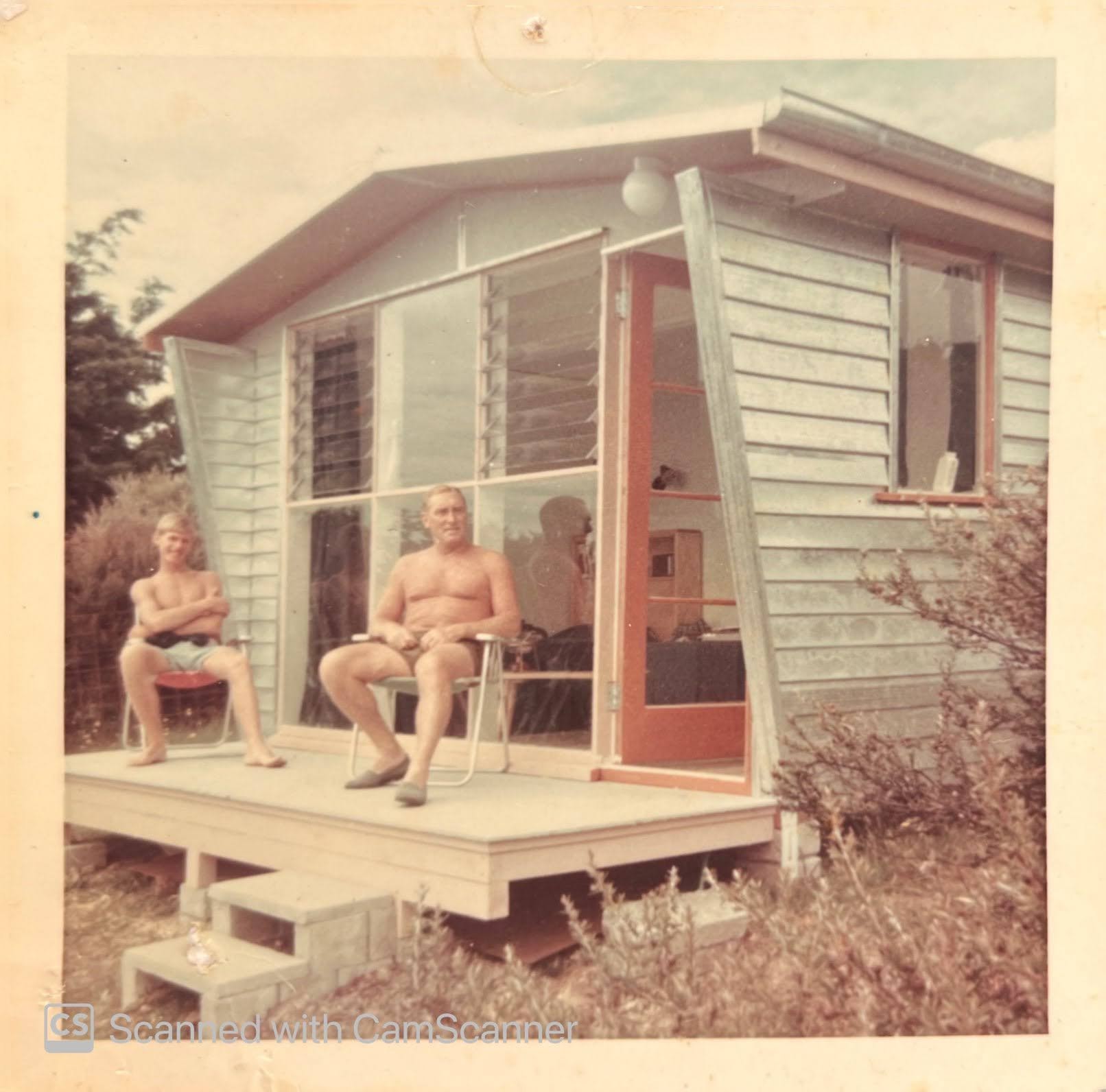

My mum and dad saved up and got a beach house at Stanmore Bay north of Auckland in the early Sixties. He bought a ridiculously heavy 12' 6'' runabout powered by a hopeless two-and-a-half horsepower Seagull outboard.

We'd drag this weighty vessel – named Rangitiki of course – down to the waves and, once we got the stubborn motor going, putter out to sea to fish or just bob around.

I grew up at that beach, six weeks every summer, in and out of the water.

In our house we had books like The Surgeon's Log (James Johnston Abraham, published 1935), Doctor at Sea (comedic) and Nicholas Monserrat's The Cruel Sea (1951).

In our house we had books like The Surgeon's Log (James Johnston Abraham, published 1935), Doctor at Sea (comedic) and Nicholas Monserrat's The Cruel Sea (1951).

I knew early on the sea wasn't cruel. Like all Nature it was just indifferent to us. If you fall overboard in the North Sea during a howling storm the winds won't die down just for your sake.

But it wasn't until later in my life I began to get a different understanding about the oceans which sustain us and surround us, the place where we scattered my dad and mum's ashes.

I was probably in my 40s when I went to Thailand and, for the first time, went snorkelling because the water was warm. It was a revelation, a genuine epiphany. Up until then my romance of the sea was all surface, here was a vibrant underwater world where fish in shoals followed submerged pathways, where there was vibrant colour, a breathtaking diversity of beautiful creatures.

I stayed in the water so long that day my back got sunburned. The next day I lay around moaning and drinking Mekong whisky to soothe the pain.

But I'd seen something that I will never forget. And I feel foolish telling of how I was so late in realising this. All those shark documentaries on television hadn't had much effect, obviously.

I mention this because today is World Ocean Day when we should celebrate and honour the oceans of this fragile planet.

The marvellous 99-year old Sir David Attenborough has spoken eloquently as always about the danger we are in. Yes, the sea is indifferent to us, but we cannot afford to be indifferent to it.

If the Amazon is the lungs of this Earth, then what is the sea but the life-blood that courses all around us, which determines the weather, all aspects of the climate and what nourishes us.

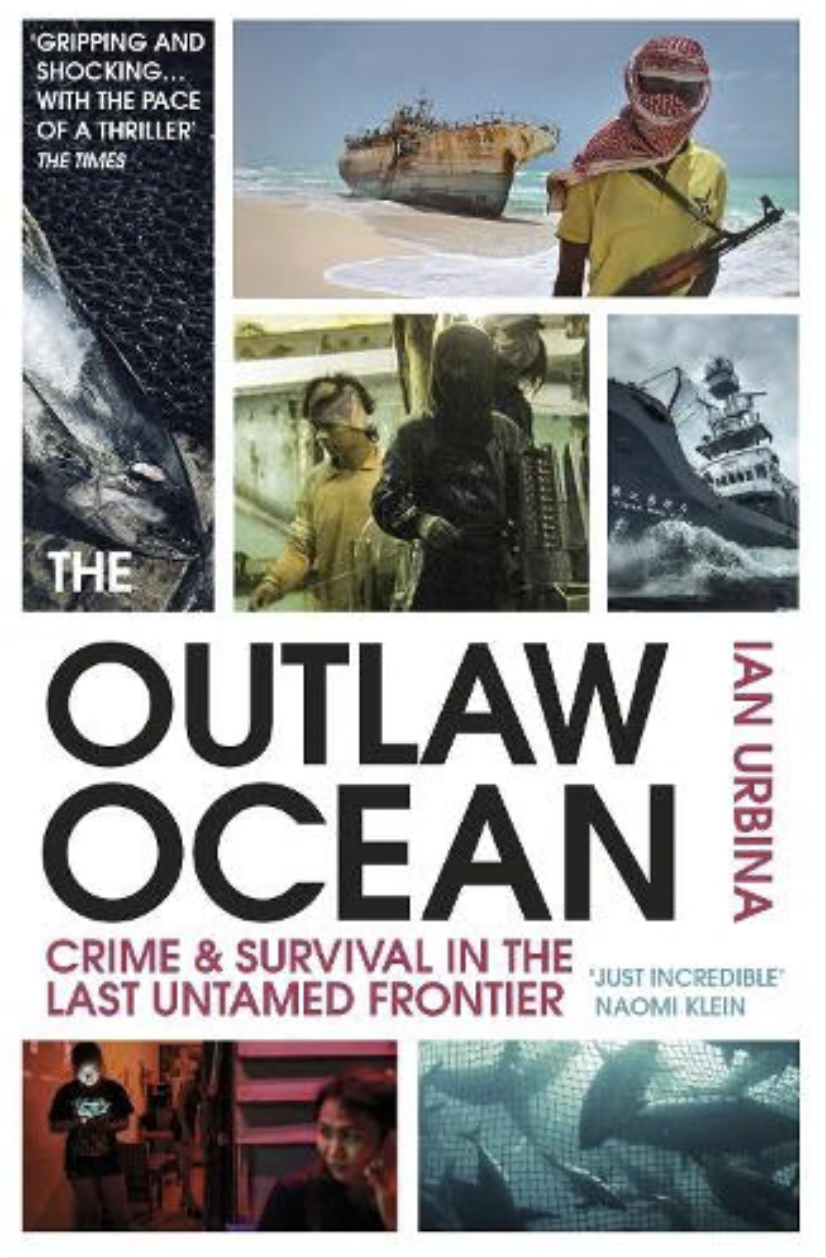

By coincidence I am currently reading the 2019 book The Outlaw Ocean: Crime and Survival in the Last Untamed Frontier by Ian Urbina.

Yes, it is a few years olden some pieces were previously in the New York Times, but I have no doubt the exploitation of the ocean by rogue fishing companies who send impoverished men (and some women) to sea in rusting, unfit boats is still happening.

Yes, it is a few years olden some pieces were previously in the New York Times, but I have no doubt the exploitation of the ocean by rogue fishing companies who send impoverished men (and some women) to sea in rusting, unfit boats is still happening.

Just go down to most ports and you'll see such vessels, listing a bit, rusted to the core. You wouldn't feel safe on the deck let alone down in the hot, constantly wet and slippery bowels where fish are sliced and diced and many discarded.

We are harvesting the fish to extinction, for greed and profit.

There is still the appalling trade in shark fins (US$100 a bowl at Chinese weddings says Urbina), crews hauling up bluefin tuna (beautiful creatures which I have seen on the floor of the old Tsukiji market in Tokyo, selling for high six-figure sums and more) and then there is the bycatch of deep sea trawling which can mean more than half the global catch is tossed overboard dead or ground down and made into pellets to feed pigs, poultry and farmed fish.

Nets destroy coral reefs which have taken centuries and more to grow.

The oceans are rising, warming and becoming more acidic. Fish now appear in places they'd never been seen before as they pursue ever-diminishing food sources and waters at a temperature they are adapted for.

Urbina's book (“just incredible” said Naomi Kline. Gripping, terrifying said other reviewers) reads like a tragic thriller because he is aboard outlaw vessels seeing the slave labour conditions many unfortunates work in; cross-checking facts that ring like alarm bells if not “last warning” and all the time the backdrop of his reporting is the ocean which is more fragile and out of balance than we perhaps believe.

Attenborough does sound a faint voice of optimism: “The ocean's power of regeneration is remarkable,” he has said.

But then added the corollary: “If we just offer it the chance.”

.

These entries are of little consequence to anyone other than me Graham Reid, the author of this site, and maybe my family, researchers and those with too much time on their hands.

Enjoy these random oddities at Personal Elsewhere.

post a comment