Graham Reid | | 16 min read

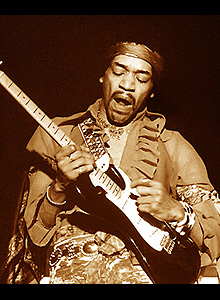

The Jimi Hendrix Experience: Purple Haze

For a man who changed the landscape of rock -- and not so coincidentally my life -- his last resting place looks extremely modest. It is late 2002 and I am standing at a simple plaque in the grass with only a single glass of fading flowers on it. There are no visitors here other than me and my companion Tommy, a Norwegian music journalist from Los Angeles.

A few minutes ago I walked into the cemetery office where a rotund woman looked at me briefly then, with mock confusion, jabbed a stubby forefinger into her right temple and said, "Now, why might you be here?"

We both laughed and, because I didn't need to reply, she wandered off to a drawer to pull out a folder then photocopy a rudimentary map for me.

"You go out here and turn right, go down the main drive to where the veterans are -- you'll recognise it, there's a cannon -- then turn left. It's along by the sundial. You'll find it."

And so, because this is a very large cemetery half an hour from downtown Seattle, Tommy and I drove to the sundial and found it: Jimi Hendrix's grave in Greenwood Memorial Park in Renton.

Hendrix died in 1970 at age 27, an icon in rock whose music went global and whose lyrics were often impenetrably intergalactic.

When he died -- unglamorously choking on his own vomit in the back of an ambulance in London -- he was brought home to be buried here under a weak, late autumn sun on October 1. Those in attendance included Miles Davis, and the crowd was a mix of rock's most respectful, some 200 fans, and his family.

It was a large and solemn funeral, almost impossible to imagine on this still and silent day under a hot summer sky.

Hendrix's plaque is simple, his career and influence discernible only by the inscription "Forever in our Hearts" and the image of a guitar. It hardly seems adequate when you consider his magisterial music.

Yet, when you think of Jim Morrison's tomb at Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, where every day leather-clad kids and rock pilgrims sit drinking wine and leaving bottles of booze and cigarettes for their dead hero, this unassuming plaque is much more moving.

As with Buddy Holly’s similarly simple gravestone outside Lubbock -- where the inscription adopts the original spelling of his family name “Holley” -- these more unpretentious markers offer the opportunity for pause and reflection to consider the man and his music, rather than be diverted by the myths which swirls like clouds of manipulative mystique around Morrison.

So between the sundial and a small tree lies Jimi Hendrix, in a quiet suburb of this city in Washington state.

But I was there years ago. And so much has changed since.

Jimi Hendrix had a profound influence on me. Like the jazz musicians Thelonious Monk and Ornette Coleman, reggae singers Burning Spear and Bob Marley, and the hip-hop artists Grandmaster Flash and rapper Tupac, Hendrix changed the way I heard music. And my expectations of what rock music could be.

I would have been 16 when I first heard him screaming Hey Joe down a radio wire from some “live in London” BBC programme. That was early 1967. I was a pimply boy who had just passed School Certificate at the time and was embarking on the first of my two years in the sixth form.

Radio was my lifeline to a bigger world than my bedroom with its Beatles and Stones posters from magazines like Rave and Playdate.

I had already discovered grubby garage band r’n’b in the form of the Animals, the Pretty Things and the Downliners Sect, and -- through my friend Barry’s older sister Rangi -- the thrill of Motown soul.

Music -- which included my Dad’s love of Louis Armstrong and my older sister’s collection of late 50s pop like Diana by Paul Anka -- was my world, and it was a big one, growing every day.

None of my friends nor I ever bought into that great Beatles Vs Stones divide that I hear about these days. At school we’d talk about the Yardbirds and Joe Tex, Dusty Springfield and Nancy Sinatra . . .

You know the rest.

And then Hendrix crash landed into our world.

The day his EP -- which featured Hey Joe, Purple Haze, Burning of the Midnight Lamp and 21st Anniversary -- came out I went down to a record shop in Newmarket at lunchtime and stole it. I slipped it under my school jersey and made off. I still have it.

In fact I have a huge Hendrix collection because in the past few decades they were repeatedly reissued on vinyl, and then again on CD a few times by which period of my life I was a music writer and being sent review copies. But I also have all the original releases, some of which I bought at the time.

Some I acquired by other means.

At that time in the late 60s record shops like Sidney Eady’s and the store in newly-opened 246 on Queen St kept albums in their sleeves in large open racks. My friends and I started a record-stealing ring which operated with remarkable efficiency every Friday night. We’d steal to order -- or more correctly we’d take orders at school and get others to steal for us. I guess it was our version of downloading.

During my 6th form year quite a pattern developed. Every Friday night Ed, Allan and I would get dressed up -- me in a checked jacket, white shirt and black knitted tie so I looked like Brian Jones on the cover of The Unstoppable Stones album -- and would go to the Royal International Hotel on Victoria St.

I was 16 and younger than them by a year, but we were never challenged once. We’d have a few beers, listen to some ancient pianist play Yellow Bird and other popular favourites, and maybe later go to clubs like The Platterrack or the 1480 Village (which I also frequented a decade and a bit later when it became Zwines, the punk club).

Inevitably we’d end up going to some party in Hillsborough or Mt Roskill in Allan’s car, a monstrous Willys, the bonnet of which I had painted with psychedelic squiggles and a satanic face over the grille.

Into this mix came the record stealing ring which included Barry and a few others.

By 67 there was a substantial population of guys with long hair in Auckland, most of whom couldn’t get jobs because of their appearance. I don’t know what they did by day, but on Friday nights we’d meet up with a few of them in various coffee bars in town. We’d pass on the list of albums we wanted and away they’d go.

The profit margins were simple: albums were about $4 so we’d pay them a dollar and sell them at $2 to the guys at school. A win-win for everyone -- except the record shops, the record company and the musicians I guess.

One night, sitting in Checkers coffee bar, we were approached by a longhair we’d never met before. He asked if we were the guys who wanted some records.

He was big and edgy, dressed in a dark long coat, and keen to earn some money. I gave him a list -- half a dozen Sgt Peppers, a few copies of the first Cream album, some Hendrix and so on -- and away he went.

But there was something untrustworthy and dangerous about him, so we sent someone to watch what he was up to.

Ten minutes later our scout came racing up the stairs.

“Get out fast,” he whispered, “The guy’s crazy. He’s just shoving stuff under his coat and everybody is watching him.”

We fled into the street, me carrying a pile of 20 or so albums we’d already acquired.

I remember as the Willys climbed the hill beside Albert Park I flicked through what I had on my lap: half a dozen copies of Sgt Peppers, a couple of copies of the Blues Magoos’ Electric Lollipop, a swag of the first Cream album Fresh Cream, and some of Hendrix’s debut album.

That was the last time our briefly profitable thievery corporation operated, but I still have that copy of Are You Experienced.

This was a record which bewildered as much as seduced me. In part that was because the labels in the middle were on the wrong side so for a few days I thought the ballad May This Be Love was the rocker Foxy Lady, and vice versa.

There was mystery and much magic in this music. I played it before I went to school, tried to decipher the lyrics, talked about it with friends, and played it last thing at night.

I also managed to produce a passable caricature of Jimi which prevented bovine First XV guys beating up my skinny frame when I started produced a few posters supporting the team with Jimi’s multicoloured face leering out of the middle.

“Get experienced -- go to the game” was one unconvincing tagline.

Everything about Hendrix fascinated me: I went to the library and ripped the page out of Time magazine about him (the article was headed ” Wild Man of Borneo” for some reason), read whatever I could find in pop magazines, and listened to his live radio broadcasts from London by turning my transistor dial in tiny incremental movements to pick up what sounded like static but which, with even more fine tuning, turned into music from the other side of the planet.

And always I kept coming back to the bewildering array of music on Are You Experienced which contained guitar sounds I had never heard before, and many I haven’t heard since.

There was a baffling stylistic diversity on the album, almost too much information to assimilate. This was music you could not walk away from. It assaulted the nervous system, confused the cerebral cortex and redefined the parameters of what was possible in popular music. It was almost too huge to contain on a slice of vinyl.

There was fuzzy, riff-laden pop on Foxy Lady; driving rock on Manic Depression; and in Red House he took you down into the blues with devastating guitar lines which acted as a counterpoint to his vocals.

There is whining, backwards guitar on the title track, and the free form 3rd Stone From the Sun paved the way for jazz-rock. At one point the says, “And you’ll never hear surf music again” and for a while I persuaded myself that he then played a snatch of surf guitar.

Allan, a surfer, said bluntly, “No he doesn’t ” and I had to go back and listen again with less imaginative ears. He doesn’t.

In his guitar work Hendrix conjured up dream states (Is This Love) and nightmares (I Don’t Live Today with it‘s drum pattern taken from the Cherokee tribe which his grandmother belonged to). And he doesn’t resile from dropping in a beautiful ballad (May This Be Love).

He made sounds like motorbikes and the whine of bombs falling, yet each was so thoroughly contextualised within the music that it is impossible to imagine the songs without them. Hendrix‘s guitar figures are his aural fingerprint, distinctive and singular.

His guitar stabs through the heart of the songs (Manic Depression) or caress like what I, as a schoolboy, imagined a lover’s kiss at midnight to be.

If there is a case to be made that it is the greatest, and most ambitious, debut album in rock, I would gladly do it.

In its musical breadth it was as if Hendrix knew he might not be here for long so wanted to create the template for anyone else courageous, or foolhardy enough, to try to follow.

I stopped playing guitar. There seemed no point anymore.

Hendrix flew across my world like a comet but within a few years, because he was a musically adventurous spirit, he wearied of the audiences’ demands for what he considered old songs like Purple Haze, Foxy Lady and Hey Joe.

And so he retreated into the recording studio which became another instrument in his hands and, as he proved on the double album Electric Ladyland in late 68, the technology was now available for him to realise his visions. The cover announced “produced and directed by Jimi Hendrix”. It was music as movie.

Released less than a year after his second album Axis: Bold as Love and only 18 months after that debut it capped an astonishingly productive period in which he had also toured relentlessly.

When the album came out I pounced, trawled for the genius, and wasn’t disappointed.

Guests on the album included Steve Winwood, bassist Jack Cassidy from Jefferson Airplane, pianist Al Kooper who had played with Dylan.

By this time psychedelic music -- if not the drugs -- were part of my world. I had bought albums by Country Joe and the Fish, Golden Earring’s live Eight Miles High and dozens of others.

But Electric Ladyland, with its phasing between the speakers, oddball aural effects, wah-wah that seemed like it was speaking to you, and more complex music was different from the slightly bent pop-rock which passed for freak-out psychedelic.

This was music of depth and complexity which invited you in, especially the coughs at the start of side three which made it seem like you were eavesdropping on a studio jam session. Then Jimi takes a hefty sfffttt on a joint and leads off into the trippy tracks Rainy Day Dream Away, 1983 and Moon, Turn The Tides which segued into each other. They took up the whole of side three, a side which I played repeatedly when I too had a joint. You just had to.

And Hendrix’s voice was a revelation: at times he would whisper, there are passages of what could be spoken word and at other times he was a full-throated rocker. His is one of the most distinctive voices in rock.

Yet as a younger man Hendrix had been hesitant about singing, he had played guitar in bands fronted by Little Richard and saxophonist King Curtis, and 50s pop survivors Joey Dee and the Starlighters.

“Once you heard him sing, you’d know why he wasn’t a singer,” said an early 60s bandmate Jimmy Jones.

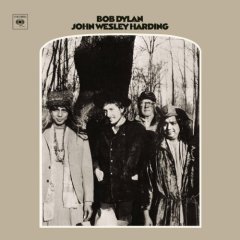

Hendrix substituted showmanship -- playing guitar with his teeth and behind his back -- to survive on the chitlin circuit down south. It is said he changed his mind about singing in 65 when listening to Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 album.

Dylan established that in rock culture you needn’t have a good voice to be a singer.

For weeks on end in 65 I had played his monotonous Gates of Eden -- the flipside of Like A Rolling Stone -- which had supplanted the Stones’ equally annoying The Last Time as the ideal parent-baiting music.

Then came Jimi.

It is ironic that Hendrix, considered a non-singer by many, should be one of non-singer Dylan’s finest interpreters. By the time of the Electric Ladyland album in 68 Hendrix had already hauled Like A Rolling Stone into hard rock for live audiences, but on Electric Ladyland he gave a Dylan song, All Along the Watchtower released some eight months previous, one of the great re-configurations.

Hendrix had started recording his version -- with Rolling Stone Brian Jones in attendance -- the same night he first heard Dylan’s acoustic album John Wesley Harding which featured this mysterious song with its Biblical allusions and a disconcerting sense of emotional dislocation and incompleteness. In the final lines two riders are approaching, and no clue is given to who they might be.

Rock culture is now littered with tribute albums and cover versions, but back in 68 this was still something of a rarity.

On stage Hendrix -- who had grown up on a touring circuit where popular covers were always part of the contract -- had no such hesitation: he’d covered the Beatles’ Sgt Peppers just days after its release and their Daytripper, Howling Wolf’s Killing Floor, both Hound Dog and Blue Suede Shoes which Elvis made famous, Van Morrison’s Gloria, Chuck Berry’s Johnny B Goode, and the Troggs’ Wild Thing. And of course at Woodstock he re-invented The Star Spangled Banner for the anti-Vietnam generation. Later he did much the same in England with God Save The Queen.

His first hit Hey Joe was also a cover.

So for Hendrix to cover Dylan’s All Along the Watchtower was no surprise, the shock came because he re-invented the acoustic folksy song as a slice of apocalyptic rock. In subsequent years when Dylan played it live he adopted Hendrix’s approach. He recognised that it had been Hendrix, and not himself, who had defined the song.

Hendrix understood the song: “I felt like Watchtower was something I had written,” he said, “but could never get together. I often feel like that about Bob Dylan.”

All Along the Watchtower is a studio creation, but more remarkable for that. It opens with a bass-heavy chop of mighty chords, what sound like punctuating shrieks then a searing guitar line which later becomes the melodic thread he will embellish.

As he sings the lyrics he brings a sense of despondent urgency not apparent in the Dylan version.

The lead guitar drops back behind the vocals, appearing as stabs of punctuation at the end of the lines, then as the first verse finishes it soars off into the skies before stuttering to an abrupt close. The voice returns for the second verse.

It is a song without a chorus so Hendrix varies his vocal approach on each of the three verses, in the second his voice is heavily echoed and as the backdrop swells like waves he seems to be surfing the mighty chord progression.

Behind him the drums and bass rumble and the second lead guitar line extrapolates on the melody he has previously established. The key to his interpretation is that each time he returns with a guitar line it is a variant on the one before, a staggering array of notes tumbling over themselves, always being hauled in abruptly so the lyrics of fate, promise and fear are thrown back into the foreground.

The guitar is expansive until the central section with its four distinct parts into which he drops through a glissando of notes like falling down a well into warm water. Then he moves into a bluesy section with slide on electric 12-string (he used a cigarette lighter apparently), it jumps into a complimentary wah-wah which phase between the speakers then it’s back to a twanging variant on the initial chords and soaring towards the final verse which opens with the song’s title.

The music behind him seems less excitable now, the punctuations of guitar notably absent or more restrained until he reaches the final line “the wind begins to howl”. The final word is echoed and repeated for effect

And, over enormous rumbling bass, the guitar lines reach for a sustained, sky-grabbing crescendo as the song fades, suggesting it could go on forever. You certainly want it to.

In 2005 I went back to Seattle for a flying visit. The kid who had drawn Hendrix on his schoolbooks was now going to see the Boeing factory to write an article for a major newspaper and collect material for another book of travel stories.

Much had changed in my world, and in Greenwood Memorial Park also.

Hendrix’s grave had been moved from the plain and quiet lawn to a more noisy spot near the road alongside the expanding area for Vietnamese with its temple and colourful decorations.

The modest plaque is still there but now it forms the base of huge plinth beneath a three-sided mausoleum. Around it are a semi-circle of other headstones, all empty and waiting for the Hendrix dynasty to take their places.

The ugly thing has had a troubled history. A decade after Jimi’s death a local radio station launched the Hendrix Memorial Project to raise funds for a statue in one of the city’s parks. The Seattle Parks Department wasn’t keen on the idea and eventually a memorial was unveiled at, of all places, Woodland Park Zoo.

The Hendrix family weighed in and the idea of statue above the site of his reburial was mooted. There was a public commemoration of the memorial planned for June 10, 2002, his father Al Hendrix’s 83rd birthday. Unfortunately Al died two months before the ceremony.

Oddly enough, it is the local company Microsoft which has given the city its most famous rock'n'roll landmark, the Experience Music Project.

This remarkable 13,000 square-metre building beneath the famous Space Needle was designed by one of the foremost architects of our time, Frank O. Gehry, who also designed the Guggenheim in Bilbao, Spain.

The EMP was underwritten by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, a Hendrix fan who has the world's largest private collection of Hendrix memorabilia, including hand-written lyrics, rare recordings and Hendrix posters, guitars and concert tickets.

Allen originally conceived a centre for the storage and study of Hendrix, but it has expanded and now the EMP is a massive three-storey centre paying tribute to the music of the Northwest, houses a collection of historic guitars, and has a performance space. There are frequent and scrupulously curated rock exhibitions, sound labs, and an 11 metre high sculpture by local artist Trimpin made up of 600 guitars and not a few drum kits. It is breathtaking in a building which has you gasping anyway.

The Hendrix area tells you everything you ever needed to know - and then some - about the loud life of the gentle man buried in the quiet suburb of Renton, now beneath that unsightly monument.

Already the graffiti kids have moved in at his mausoleum. Michael from Ireland has written “Scuse me while we kiss the sky” and someone else has scribbled “we luv you”.

It seems such a shame.

Like Morrison’s grave in Paris this no longer feels like a place where you can quietly consider the life of this musical giant.

But to discover Jimi Hendrix you could simply start with his extraordinary interpretation of Dylan’s All Along the Watchtower.

It is distilled genius.

Richard Aston - Apr 13, 2015

Thank you for , " All Along the Watchtower.... It is distilled genius."

SaveA song I have been listening to since it first came out and I never tire of it .

The first proper rock song I learnt on guitar but had to stay with the Dylan version rather than stretch it way out to the Hendrix .. I was going to say version but.. reinvention .

In the late 60's those of us playing guitar would try to learn the rife of Jimmy Page etc compare notes and we did learn a few Hendrix riffs but got nowhere near that sound. We heard rumours of guys sneeking into Henrix's recording studio to find out what effects units or custom made guitars he was using , the word back from the spies was in hushed tones , nop just a strat ( right handed strung for left hand) , a huge stack of marshal boxes and a wahwah peddle . That was it . Well I dont' know if that was true but I loved the legend of it. He become god like at that stage.

Such a loss

And he kept developing and growing ... Pali Gap from the posthumous South Saturn Delta album is so different

post a comment