Graham Reid | | 12 min read

The city is melting by mid-morning. One of the newspapers - under the thumping headline "Blast Furnace" - says the Met Office is predicting the hottest day of the month: a withering 42C.

Summer is scorching its way to town, so Sydney responds with shirts off and shorts on.

And by coincidence the soundtrack beneath the hiss of bus brakes and rattle of trams around Circular Quay is one of the Beach Boys' geriatric but still youthfully cheerful summertime hits, I Get Around. It rings out from a battered transistor nursed by a beggar on a blanket.

Do I mention this to Brian Wilson, the former Beach Boy who penned all those legendary early 60s songs about endless summers and fun? Would he, who plays to a sold-out Opera House on this night, be flattered?

Or would the man whose life spiralled downhill from the late 60s into depression and paranoia simply flip out?

"You're kidding?" he laughs. "Oh, that's great. I'm very proud of myself that I could have written those songs when I was a young kid, when I was 24, 25. I was a different person then because I was more competitive. I'd run into the studio and make records and run to my house and write. I was moving at a faster pace then; I don't move so fast now."

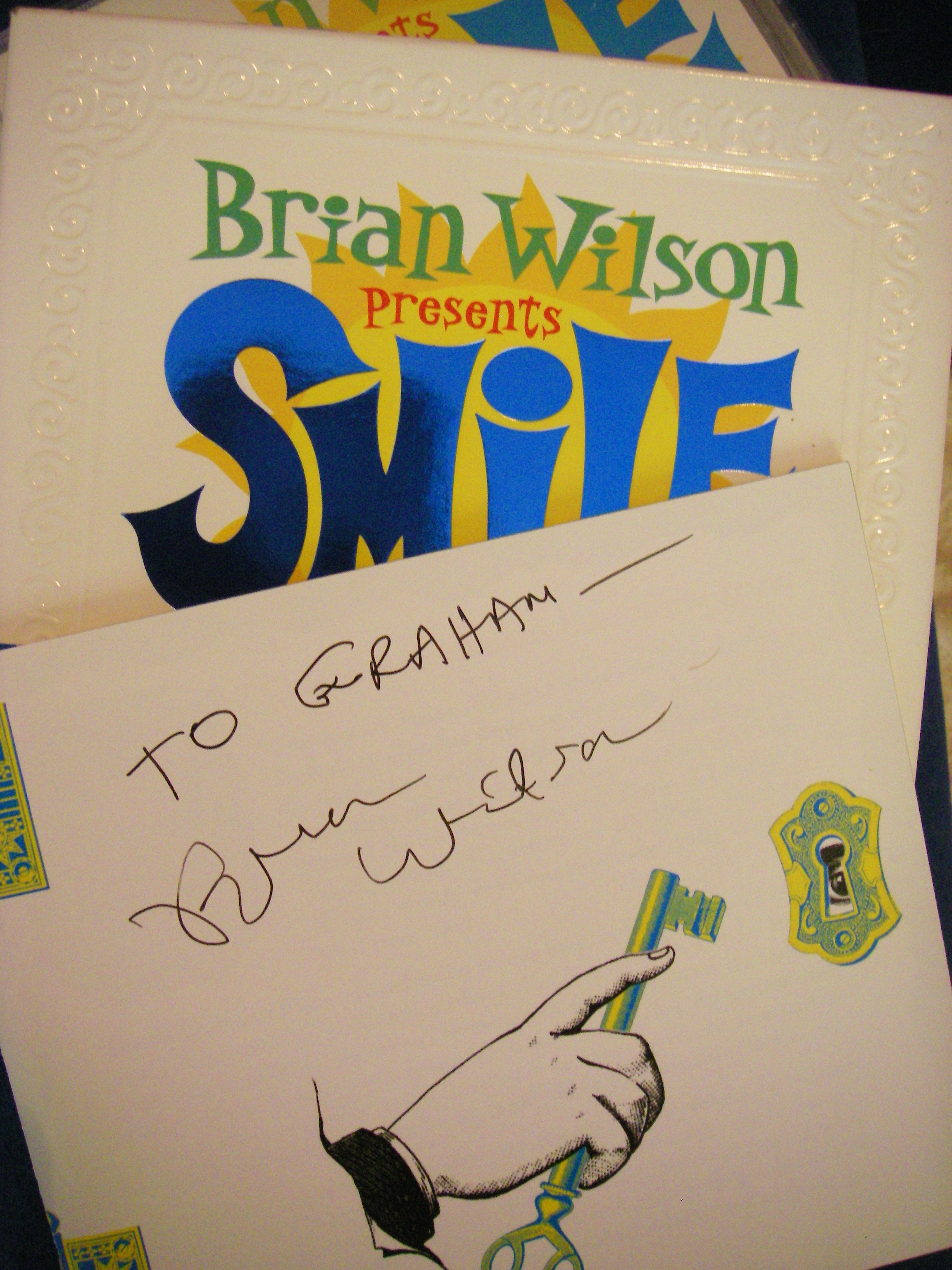

This admission should occasion laughter given that Wilson has recently completed, and is currently touring, his album Smile, the legendary lost album of rock which he abandoned in early '67 and only recommenced recording last year.

If anyone doesn't move so fast, it's Brian Wilson.

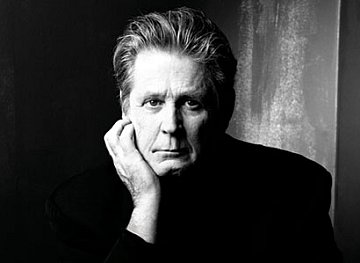

It is just before the afternoon soundcheck at the Sydney Opera House and Wilson is sitting in an unglamorous backstage room, bare except for four uncomfortable chairs and a barren desk. At 62 he looks remarkably well for someone who suffered chronic obesity, a breakdown and prolonged depression, and has survived various therapies.

And the man who was notoriously reclusive and uncomfortable in company now gets out and about. Yesterday he signed 200 albums at the nearby HMV Store, he's doing interviews, playing live - which he quit periodically with the Beach Boys - and even walks the street.

"I enjoy touring now and I exercise every day, about two hours a day of walking. And in Australia that's a long time with the heat. So now I've got some sunshine and am feeling good. Now and then people will walk up and say they love Smile and love the music.

"I like playing with my band better than I did with the Beach Boys; the Beach Boys just weren't that good. My new band is instrumentally and vocally very much better and I enjoy stage performances with them much better than when I was with the Beach Boys back in the 60s and 80s."

He smiles that famously lopsided grin and maintains the unwavering pale-eyed contact.

Wilson's rapidly delivered answers are clipped and sometimes repetitious. But aside from the occasional mishearing of a question - he has been deaf in one ear since an early age, possibly as a result of a beating from his father Murry - he seems confident and comfortable, although there is a well-practised phrasing to some of his replies.

He is accompanied everywhere by Jerry Weiss, with whom Wilson says he is writing songs although Weiss prefers just to describe himself as a "friend".

But otherwise Brian Wilson, one of rock's most notorious casualties in the 70s, seems okay.

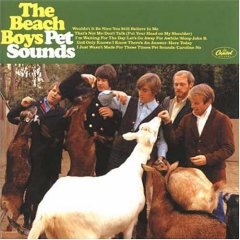

Almost 40 years ago Wilson, described as a genius of pop for his string of cheery but harmonically complex Beach Boys hits, was at the top of his game. Then with the Pet Sounds album of '66 - which included timeless songs such as Wouldn't It Be Nice, God Only Knows and I Just Wasn't Made For These Times - he was creating music of complexity, emotional depth and nuance, with just enough of a whiff of psychedelia to carry it to a mature audience which had wearied of the Beach Boys' high school pop.

Wilson had found his niche, and it wasn't on the road with the Beach Boys. It was in the recording studio where he would craft the songs for the band to record.

But with the classic Good Vibrations of late '66 and then his concept album Smile in '67 the Beach Boys, notably singer Mike Love, baulked. Their once-familiar sound was getting weird, darker and complicated, and that might mean no hits and no income. The lyrics of Wilson's earlier song came back to haunt him, "I guess I just wasn't made for these times".

Wilson was part way through Smile - a "teenage symphony to God" as he described it - when he fell to pieces. Some say his nerve failed after he heard the Beatles' Sgt Pepper's (a timeline of the Smile sessions probably refutes that), others say criticism by the band combined with business problems was too much for his fragile emotional state. Certainly his constant intake of marijuana and the odd acid trip didn't help.

Wilson cracked and Smile remained the great lost album of rock.

In subsequent years a few tracks - Heroes and Villains and the sublime Cabin Essence among them - appeared on Beach Boys albums. Over time bootleg reconstructions using out-takes and available material appeared and the Smile cult grew.

Not that Wilson knew about it - for decades he was battling his demons through emotional withdrawal, then therapy and exercise.

"There were bootlegs? No, I never heard of any of those bootlegs," he says with genuine surprise. "Were there really bootlegs? Wow, I did not know that. Didn't know it. I guess we killed them when we put the new Smile out."

And he laughs for a rare moment, slapping his palm on the table.

The past decade has been a healing one for Wilson. After a demon-exorcising autobiography, Wouldn't It Be Nice, in '92; he again co-wrote with his former Pet Sounds/Smile lyricist Van Dyke Parks for the Orange Crate Art album; and four years ago he started touring the Pet Sounds album with his new backing band the Wondermints, helmed by Beach Boys fan Darian Sahanaja.

This year Wilson released the solo album Gettin' In Over My Head with guests Elton John, Paul McCartney and Eric Clapton; and now he has toured Smile and released the album.

"I feel like a bad part of my life came to an end and the good part started when I released Smile. And [Gettin' In Over My Head] softened up people and created waves for people to buy Smile."

As one of the most overdue albums in pop, Smile - reconstructed with help from Sahanaja and Parks - was always going to gather attention. Wilson says he abandoned it because it was too ahead of its time, yet even now its mix of a cappella and pop, animal noises and sublime harmonies, Hawaiian music and almost indecipherable lyrics from Parks means it also doesn't sound like anything around today either. Which - along with its oblique concern for a lost Americana - makes it enormously attractive.

"I think finally people have caught up with it and I think they are going to like it very much. It was too advanced, but people are finally ready for it."

So if you wait long enough your audience will come to you?

"Yes, that's it," he laughs suddenly, then resumes his intensely focused expression.

"I now call it 'a happy teenage symphony to God' because it's a three-movement rock opera and it's a happy and jovial album. When I talk about God I mean music therapy, music that is good for your soul. There's not a lot of healing music around and this is why Smile is so important, to heal people and make them feel good from all that bullshit that's on the radio now."

Not that Wilson knows what's on radio, he says he only listens to Phil Spector and Paul McCartney.

But an invigorated Wilson says after the Smile tour he has another project starting in January, a rock'n'roll album co-written with Parks and Weiss.

"I want to try something that's more exciting even than Smile, something that makes people want to dance like Phil Spector's records. Smile is music for the head but rock'n'roll makes you want to move."

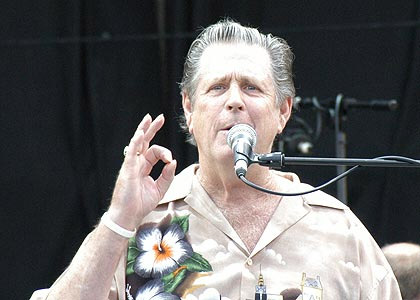

Five hours later at the Opera House, Wilson and his big band deliver a concert which makes the audience think and move.

Over the two hours and 20 minutes you are reminded what a musical reach Wilson has, from melancholy to magical, from Bach-like vocal arrangements to an incendiary psychedelic freakout in the fire section of Smile called, improbably, Mrs O'Leary's Cow.

The audience laughs (when the string section do The Swim and the band clown around) and dances along with classic Beach Boys songs.

Opening with an acoustic set surrounded by 10 musicians they kick in with a gorgeous version of Surfer Girl. The set moves through some classic Wilson tunes (Add Some Music To Your Day) and picks up pace in the electric set.

It is a musical and emotional journey: in recent songs like Desert Drive Wilson neatly flips the Beach Boys' surfer dreams for a trip into the arid California hinterland and he nods to his late brother Carl with Soul Searching. He delivers up gorgeous material such as Sail on Sailor and God Only Knows (which he introduces as Paul McCartney's favourite song) alongside the elevating pop of California Girls.

I am seated about 10 rows from the front, right in the centre. Two rows in front of me is Jerry. I watch him as he watches Brian. And then I notice something, he is constantly gesturing to Brian -- sometimes gestures which look like "be more upbeat", sometimes he is mouthing the lyrics or discreetly waving his hands like a conductor. I don't know how much of this Brian, seated and with a laptop in front of him, is observing. But it is a very strange double act.

There is no lip-synching (Wilson is sometimes off-mike and no one covers for him) and the multi-instrumentalist band members confirm his assessment of their formidable talents. Wilson mostly sits rigidly at the keyboard and sings but, ironically, he rarely smiles.

The second half is Smile performed in its entire musical complexity. Musical signatures weave in and out, it moves from American country to Hawaiian sounds seamlessly. It confirms Smile as one of the most extraordinary and ambitious suites of rock music ever conceived. But not without humour either: for Mrs O'Leary's Cow the band don fire helmets in a referential joke. When Wilson was spinning out 40 years ago he insisted musicians wear helmets when recording this track.

The encore has the Opera House crowd up and dancing through classic Beach Boys songs, a twentysomething in a Beatles Revolver T-shirt yells "Sgt Pepper's sucks!" and his girlfriend shouts "We love you Brian", then Wilson comes back for the brief and beautiful Love and Mercy.

Right at the end Brian waves and nods, and a band member reminds him to wish us merry Christmas. Then he is gone.

It has been a night in the company of a pop genius, a chance to acknowledge his life and efforts, and to just dance.

But pathos, too, is at hand: a man who was given so little love by his family, many friends and even a record company which his hits once helped underwrite, has made music full of it, and full of compassion and forgiveness.

Smiling people filter out into the warm night, there is a crowd around the merchandising for the T-shirts and informative tour programme.

The following afternoon I see Brian and Jerry going for their walk around Circular Quay. The guy on the blanket is gone.

Still buzzing from the concert, I approach Wilson to tell him how much I enjoyed the show. Jerry has fallen behind to talk with someone as I come within Brian's sightlines. He looks suddenly alarmed and swivels his head as if looking for an escape. I can see Jerry behind him quickly terminate the conversation he is having and walk quickly, almost run, to Brian's side. It is an uncomfortable moment and I extend my hand to Jerry saying that I interviewed Brian yesterday. He remembers me and we shake hands.

There is a palpable tension however and Brian still looks uncertain. So I tell him that we spoke yesterday and I just wanted to say how much I had enjoyed the show.

He says he remembers me and says thank you.

But he doesn't smile.

post a comment