Graham Reid | | 7 min read

He tells his daily visitor, local artist Antonio Pitxot, "Today I am going to die." And there is every reason to think he might.

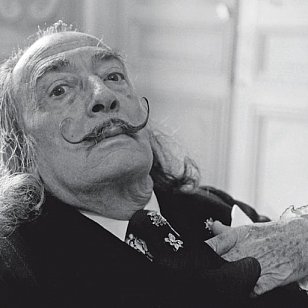

For 83-year-old Salvador Dali, at one time the brightest star in the surrealist firmament, these are tragic days indeed.

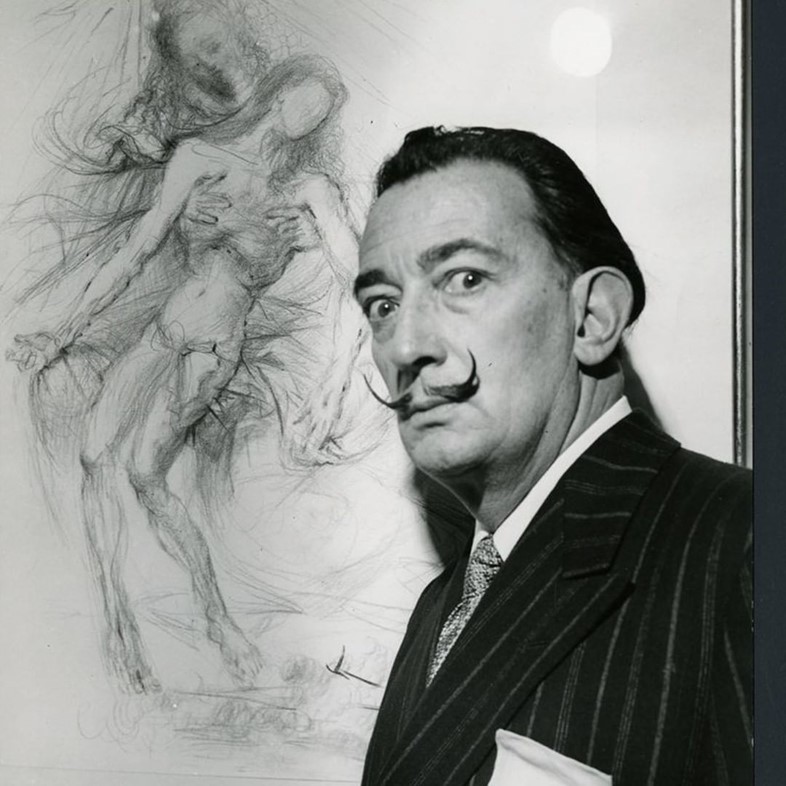

Once the darling of the American and Parisian chic sets, arguably the greatest living surrealist artist (with the important corollary that he has hardly produced anything approaching his finest work since the mid 50s), this eccentric old man still remains in control of his prodigious intellect.

He discusses plans for extensions to the Dali museum, the bizarre building on the other side of the locked door and across the courtyard which houses a collection of his work. He is curious about technology and discusses art at length.

But, many days, Dali -- his hair now silver and his distinctive moustache but a poor imitation of its former self -- lies silent.

Dali's artistic decline can be measured in the pages of the media which he courted so shamelessly.

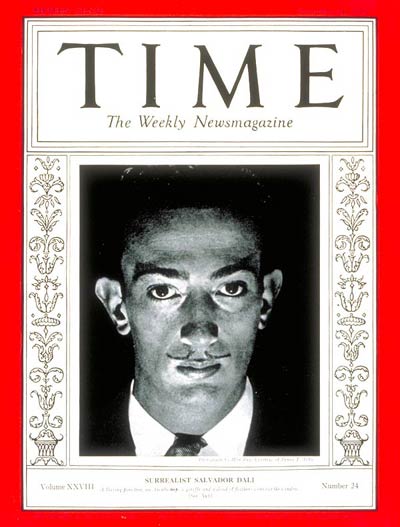

In December 1936 he was on the cover of Time magazine, the accompanying story noting his "facility for publicity which should turn any circus press agent green with envy."

But the article also acknowledged the artist's "extraordinary technical facility as a draughtsman" and commented favourably on his stature as an artist.

By 1945 Time was calling him "a slick painter and calculating showman who has made surrealism into a lucrative sideshow."

By 1945 Time was calling him "a slick painter and calculating showman who has made surrealism into a lucrative sideshow."

By the early 1970s Dali was reduced to supervising a photo-spread of banal secondhand images and nude models for a Playboy colour section.

In the accompanying text he was asked to explain the meaning of photo-collage compositions: "The meaning of my work is the motivation that is of the purest . . .money," he admitted with a candour which recalled the anagram disenchanted surrealists had given him decades before: Avida Dolares – greedy for dollars.

BUT IF Dali is remote and silent, the art world is buzzing about this once prolific and notorious painter whose painterly skills were once the equal of his media-grabbing sensationalism.

Today, interest in Dali has been rekindled.

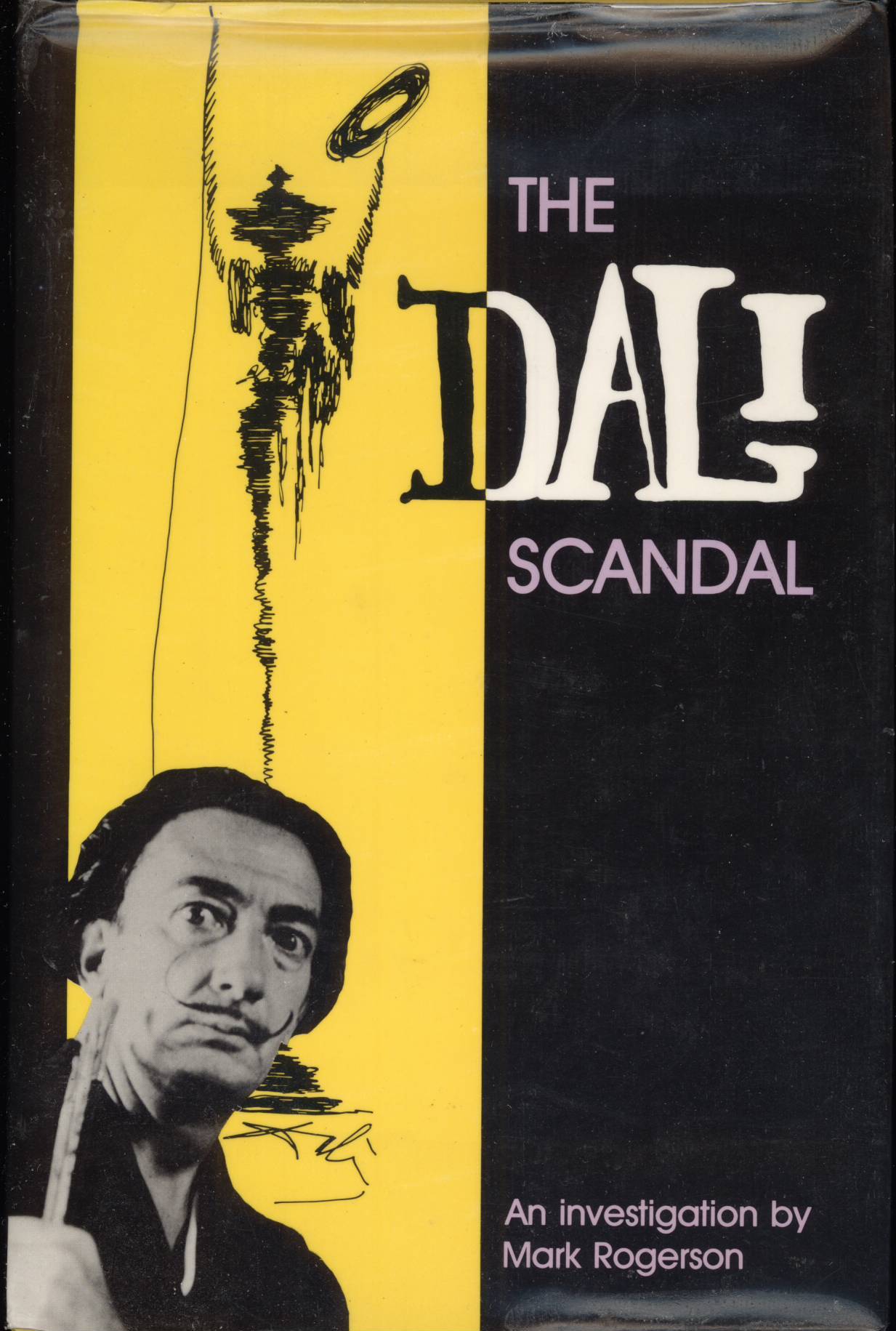

A recently published book, The Dali Scandal by British journalist Mark Rogerson brings together much of the information on what has been called "by far the greatest art scam in the long history of art" – the number of forged Dalis in circulation.

The book is a timely one. Dali suffered considerable injury in a mysterious fire in his home in 1983 and has recently had heart surgery.

His death will undoubtedly escalate the price of much of his work.

His death will undoubtedly escalate the price of much of his work.

Not all of the artist's enormous output will increase in value however. In the early 1960s Dali retreated into pastiches of his own imagery . . . quasi-scientific pictorialism and visual quotations from masters like Vermeer and Velasquez, two artists with whom he most closely identifies.

That narrowing of imagery allowed even the most primitive of forgers to produce acceptable-looking Dali works and, as Rogerson points out it his highly readable book, many of Dali's later works are little better creatively than the fakes and forgeries which have flooded the marketplace.

Add to that the persistent, and now verified, rumours that Dali signed thousands of blank sheets in preparation for series of works which were never completed, and you have the making of a lively scandal.

And questions raised, about the ability -- and --willingness of dealers to identify a Dali forgery.

IMMEDIATELY, certain things need to be made clear.

It is largely irrelevant to the Dali debate whether the artist painted all his oils, especially those from 1955 onwards.

His assistant, Isidoro Bea, joined him at that time and the studio output went up from an average of one painting a month to one painting a week, the claim being that Bea painted large sections of canvases which Dali could not be bothered doing himself.

One can feel some sympathy for the Dalinean argument that such assistance has

been common in art. It hardly seems to have troubled those who admire work from artists as diverse as Giotto and Warhol, both of whom designed but did not entirely execute the works associated with their names.

The Dali debacle centres on the thousands of drawings, "limited edition" lithographs and prints currently in circulation,

Dali's secretary-business manager for eight years until 1975, Irishman Peter Moore, is the source of the remarkable story of the artist signing an enormous number of blank sheets of paper in preparation for commissions.

According to Moore, in the 1960s Dali stockpiled a huge collection of sheets, signing at the rate of one every two or three seconds as one assistant slid the paper under his pencil and another pulled away the signed sheet.

According to Moore, in the 1960s Dali stockpiled a huge collection of sheets, signing at the rate of one every two or three seconds as one assistant slid the paper under his pencil and another pulled away the signed sheet.

Onto these sheets were subsequently printed unauthorised reproductions of paintings, drawings and etchings, all sold at grossly inflated value because of the presence of the famous signature.

Yet even the authenticity of Dali's signature, which has undergone many changes over the years is in doubt on so many “Dali originals”.

Moore, who owns a collection of more than 1000 graphics and 500 watercolours, oils and sculptures by his former employer, has written a book entitled Les 687 Tres Riches Signatures de Salvador Dali which illustrates how the artist's signature has changed so often that almost any scribble of D-A-L-I could be genuine or, more appositely, a fake.

THE WATERS are muddied even further in matters of authenticity when Dali denounced an August 1982 exhibition of Dali works from the Moore collection as 80 per cent fake.

Moore's rejoinder was as terse as it probably was true: "Dali denies authorship of those pictures which don't satisfy him anymore," he is reported to have said.

Rogerson's book analyses the complex machinations which entwined business and personal relationships and led to the exploitation of Dali in the late 1970s: over-protectiveness – for investment purposes or through a genuine love of the artist – led to a glut of disputed works on the buoyant art market.

Dali's wife Gala, who died in 1982, is identified as being irresponsible with money, prone to costly infatuations and enthusiastic about her husband undertaking lucrative commissions even to the point of signing contracts on his behalf in 1980.

Dali has also suffered at the hands of those who don't – or won't --distinguish between a photographic reproduction and a print (essentially the difference between a high quality poster and something which the artist has supervised then signed).

Dali has also suffered at the hands of those who don't – or won't --distinguish between a photographic reproduction and a print (essentially the difference between a high quality poster and something which the artist has supervised then signed).

Dali's liberal attitude towards signing blank sheets and contracts has meant that literally thousands of posters have been sold as prints and so-called "limited edition" print-runs have been extended well beyond what was originally specified.

An edition of prints may be limited to, say, 400 and each print will be numbered; 36/400 means that the print is the thirty-sixth print pulled in a total edition of 400.

After the end of a print run the original, whether it be an etching, engraving, lithograph or whatever, is usually destroyed.

In Dali's case it seems that not only were the originals, in many instances, not destroyed, but any notion of an edition being "limited" was an alien concept.

For a number of works, so-called "limited editions" were grossly extended and the purchaser ended up buying something which was not as limited as the dealers led them to believe.

Doubts are raised about the difficulties in preventing such practices and Rogerson questions the willingness by Dali and others to do anything about it.

Despite the fact that Dali has publicly stated that he stopped signing blank sheets in December 1980 and has bemoaned the fake work, he has adopted an ambivalent attitude at other times.

Indeed, despite his protestations, he is on record as saying the number of forgeries in existence is a measure of his fame.

ROGERSON'S book marries the anecdotal with investigative aspects and is at its best when he probes some of the forgeries in existence.

One example concerns the complex history of an oil titled Symbolic Figure, bought by an American millionaire in 1974 for US$15,500.

Although the artist had painted a watercolour of that title -- which he signed -- he had never done an oil by that name.

The American, realising his purchase was a fake, sold the painting for US$1000 to an art appraiser with the ironically appropriate name of Cheek.

Cheek subsequently sold the painting four years later to a gallery in Hawaii for US$50,000.

When the Hawaiians discovered the fraud they sued Cheek for damages of US$300,000 plus the original purchase price.

The painting then disappeared until 1981when it was offered for sale for no less than US$1 million together with a certificate of authenticity signed by Gala and Dali with the painting inscribed by Dali "authentique."

Whether Gala or Dali knew what they doing is an open question. Both seem disconnected from the realities of forgeries: Dali through age and incapacity, Gala through poor advice, deceit or avarice.

Perhaps the most telling comments in the book come from Manuel Pujol Baladas, an artist from Dali's province who was arrested in 1983 for manufacturing Dali pastiches.

But Pujol convinced the court that he was an innocent victim of smarter colleagues and also suggested that Gala had encouraged him to produce the fakes -- a claim, it should be said, that cannot be proved.

But Pujol convinced the court that he was an innocent victim of smarter colleagues and also suggested that Gala had encouraged him to produce the fakes -- a claim, it should be said, that cannot be proved.

Pujol observes, correctly one feels, that the lonely old man propped up in the bed next to the museum of his works is surrounded by interest groups and not by love.

That, perhaps, is the greatest tragedy of all.

.

Salvador Dali died in January 1989. He was 84 and is buried in the crypt of his museum in Figueres.

.

There is an Elsewhere travel story about a visit to Figueres and the Dali museum here.

Patrick Smith - Feb 7, 2023

Nice story G. What goes around… and around!

Savepost a comment