Graham Reid | | 4 min read

The end of the back garden at Charles Dickens' birthplace (right) in Portsmouth was shaved off in the Seventies for the M275 which aims north to the A3 for London.

A shame – although Dickens, a “navy brat” in current parlance, only lived here for five months – but perhaps emblematic.

By coincidence, the cul-de-sac in front of Dickens' first home -- then Mile-End Terrace, these days Old Commercial Rd – was once the main route to London just 100kms away, the life of which he frequently fashioned into fiction.

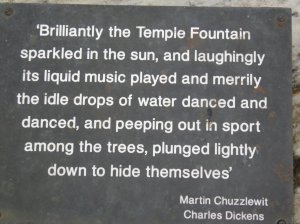

At Dickens's birthplace (below) there's not much of his, although there is the green lounger he died on, his life therefore conveniently bookended in this comfortable middle-class home.

But bombing during the Second World War took out two other Dickens family homes in Portsmouth and rapacious development has meant much of Dickens' world, in London and elsewhere, has been taken from us.

Yet, in the bicentenary of his birth in 2012, pockets still appear unexpectedly.

Yet, in the bicentenary of his birth in 2012, pockets still appear unexpectedly.

In Dover – where he wrote parts of Great Expectations and Bleak House – there's a plaque at Dickens Corner acknowledging where David Copperfield ate a loaf of bread while searching for his aunt Betsy Trotwood.

In London the 16th century Old Curiosity Shop on Portsmouth St, which claims to have inspired Dickens' novel although there's no supporting evidence, is just around the corner from Lincoln's Inn Field where he would visit his friend and first biographer, John Forster. And nearby is rather swanky Chancery Lane – which appears in Bleak House – and the courts he attended as a young clerk.

Wherever you search for Dickens, fact and his fiction blur. “The very texture of of Dickens's life affected the nature of his fiction,” says Peter Ackroyd, who wrote a thorough biography in 1990. “The 'life' and the 'work' are all of a piece . . .”

While some illustrious places Dickens would recognise remain – the noisy backpacker hostel Clink 78 on Kings Cross Road was once a law court he attended – much of Dickens' London has suffered the rude incursions of time and progress.

He once roomed by the Thames but when the Embankment was created the building was demolished. It's a familiar story when walking where Dickens – in a world of gaslight and moonlight so the edges are mysterious to us – once did.

Yet Dickens can also seem unexpectedly modern and present. He was at the beginning of the age of photography, the steam ship and train travel so we have images of him in formal and family settings, and his accounts of travels through Britain and France, and the United States where he was enormously popular (although he considered it “a low, coarse and mean nation”).

The ancestors of today's internet pirates would knock off copies of his novels, he had to fight for royalties from publishers (Americans notably), and by the end of 1838 -- even before the story was finished -- there were three stage adaptations of Oliver Twist, a narrative so popular a dozen reductive films, the musical Oliver! and various television miniseries brought Oliver, Fagan and the Artful Dodger into the 20th century and beyond.

And because he was such a towering figure in his lifetime – anonymity to fame in just three years between Sketches by Boz and The Pickwick Papers in 1836 when he was just 24 – his original manuscripts have been preserved showing tiny handwriting, the multiple corrections and edits as he reached for just the right phrase.

We can also see his reading copy Oliver Twist with his emphases underlined. When he comes to Bill Sikes's murder of Nancy, in the margin Dickens has written dramatically and to rev himself up, “Terror to the End!”.

Today we know Dickens' work by reputation if not the detail of his bewildering cast of characters. But his London, a living organism as much as the theatre set for his novels, was changing before his eyes.

He was nostalgic at 23.

Almost 30 years later he took a poetic wander about London's quiet cemeteries for City of the Absent, again reflecting on what had passed. Much as we might want or wish Dickens' London to still be there, the attritions continued with increasing rapidity and most of the seediest aspects of his city disappeared.

The eccentrically theatrical characters populating his books have largely gone too because of workhouse and penal reform which the author could claim to have instigated, two world wars, unionism, Thatcherism and New Labour, pervasive Pret A Manger culture, and health and hygiene legislation.

Yet Dickens and his spirit will never be lost to the city which, rightly and with self-interest, reveres him as its greatest chronicler. It is in faces more than places where Dickens still lives.

One afternoon, in a pub near Leicester Square, a man of indeterminate age beyond 50 – swathed in a tatty scarf, worn overcoat and shuffling on scuffed boots – entered and quietly ordered a pint. He was stooped, his ineptly-shaven face a doughy pallor and his thick lank hair swept back from a broad brow coiled beyond his collar.

He cupped the beer, his long hooked nose over the glass. A man rumpled by life, familiar a century and a half ago when our author paced these streets, watching and recording.

He seemed, and there could be no more apt description, Dickensian.

post a comment