Graham Reid | | 5 min read

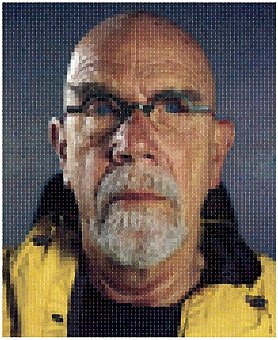

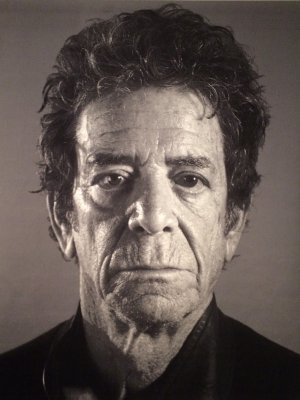

In Sydney's newly renovated Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) there is a remarkable portrait of the late Lou Reed.

It is an enormous piece by the American artist Chuck Close who is renown for such large-scale “heads”, his preferred term for his full face, usually front-on portraits.

Those familiar with Close's work know where this is heading: Lou is one of Close's hyper-real paintings which uses a photo as source material, right?

From two metres away Close's heads looks like photographs rendered huge, but the nearer you get the more you can see the detail of brushstrokes and subtle gradations of colour.

Initially that is what Lou looks like also, but get near – as you may, there's no rope keeping you back – and something else becomes clear.

This 2012 work isn't a painting, but a tapestry.

The astonishing touring exhibition

Chuck Close; Prints, Process and Collaboration – which

started in 2003 but has pieces added, like Lou, as the artist

offers them – is full of such surprises and is a rarity in the art

world.

The astonishing touring exhibition

Chuck Close; Prints, Process and Collaboration – which

started in 2003 but has pieces added, like Lou, as the artist

offers them – is full of such surprises and is a rarity in the art

world.

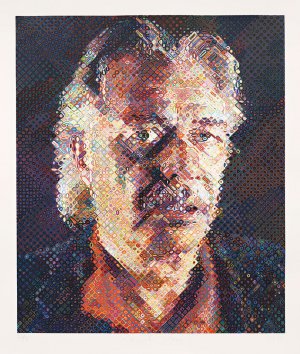

It's not just about the finished product but in room after room we see Close's working methods and how he created his lithographs, prints, etchings, tapestries, woodcuts and paintings.

“When he was a kid,” says consultant curator Glenn Barkley who spent time with the 74-year old in his New York studio, “he was gangly, had asthma and was ADD. But doing magic was his way of being popular with other kids.

“But after he did the trick he'd tell them how it was done. So this exhibition is like that.

“That's the magic trick there,” he says gesturing to final print John, the result of 126-colour screenprints. But also in the room are the earlier versions made during the process so we can see layer upon layer of colour added.

“But even though he's showing you how he does it, the trick is no less magical.”

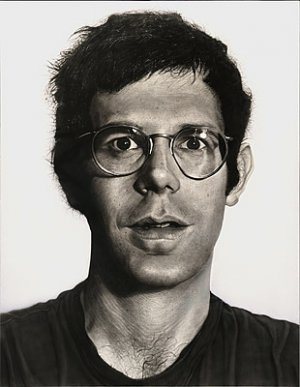

The extensive exhibition comprises

works from across the broad spectrum of Close's practice and also

includes highly significant pieces, such as the painting John

from 72 (right) and the mezzotint print Keith/Mezzotint, which the

National Gallery of Australia bought in 75.

The extensive exhibition comprises

works from across the broad spectrum of Close's practice and also

includes highly significant pieces, such as the painting John

from 72 (right) and the mezzotint print Keith/Mezzotint, which the

National Gallery of Australia bought in 75.

Keith is the largest mezzotint ever made and the gallery also bought the numerous working proofs which now fill one gallery.

In the early 70s Close approached San Francisco printmaker Kathan Brown and asked if she had ever done mezzotint. She replied not really and, says Barkley, “Chuck said: 'Let's do that because then we can both learn how to do it'. Then he asked, 'What's the biggest you can do?' and she said it was 9 x12 inches. That wasn't big enough; he wanted the biggest plate they could make. It was so big she couldn't even get the press into the building.”

The result is a work 51 x 41 ½ inches (129.5 x 105.4cm) which Close hasn't seen in almost 40 years.

Close's life and work is full of ironies: the man who creates these large “heads” of front-on faces from photographs suffers from prosopagnosia, a condition which means he doesn't recognise people's faces, even after a number of encounters.

“The curator Terrie Sultan was saying that if he took your photograph while you were sitting in front of him and you moved your face after he turned away, when he looked back he wouldn't recognise you.”

And since 1988 Close has been confined to a wheelchair after a spinal artery collapse rendered him a quadriplegic. Yet he has never stopped working, and what he does is often time-consuming, technically difficult and demanding on the many he collaborates with.

Barkley tells of one of the printmakers

who worked on the 126-colour John (right) having a photo of her

collapsing at the printing press.

Barkley tells of one of the printmakers

who worked on the 126-colour John (right) having a photo of her

collapsing at the printing press.

“She said on that day they gave Chuck a voucher for one extra colour, and it was only valid until the end of the day. He pushes them as hard they can be pushed, and these are the best print-makers in the world.”

In room after room at the MCA we can see Close's work across numerous techniques like the almost lost art of Woodburytype photography/printmaking from the 19th century.

Close had to teach himself the process and it required a press with the capacity to exert enormous pressure to create the plate, then another requiring careful control to pull the final print.

The work using this method from just two years ago are Willem and Brad (yes, the actors Defoe and Pitt) and their faces stare out as if from a much earlier time. A survey of Close's subjects is interesting: Lou Reed, these actors, photographer Cindy Sherman (a watercolour built up of a series of squares using a flat-ended brush which Close had strapped to his hand) and the musician Philip Glass whom Close photographed in the late 60s, long before Glass became famous.

“Chuck liked that photo,” says Barkley “and kept using it over and over. So you see a lot of images of Philip, the person Chuck's portrayed the most after himself.

“Philip Glass doesn't like the images and Chuck tried to give him one for a long time, and finally Philip took it. Two weeks later Chuck went around to his house and asked where it was. Philip said 'I didn't like it so I gave it to my mum'.”

Many of Close's works are a triumph over time-consuming technique, few more so than the intricately detailed cross-hatching pieces built up of thousands of fine lines scratched into a surface, or the spitbite etchings where spit is mixed with the acid to fix it.

Close worked with the famous French

printmaker Aldo Crommelnyck - Picasso and Matisse's printmaker - so

used Crommelnyck’s spit because his own didn't quite work as well.

He was convinced it was all the Gauloises cigarettes the Frenchman

smoked which made his spit special.

Close worked with the famous French

printmaker Aldo Crommelnyck - Picasso and Matisse's printmaker - so

used Crommelnyck’s spit because his own didn't quite work as well.

He was convinced it was all the Gauloises cigarettes the Frenchman

smoked which made his spit special.

Whether it be paintings, tapestries, etchings, pulp paper creations (right) or images built up laboriously over weeks and sometimes years, the Close exhibition is an insight into an artist whose work is so rigorous, and both intellectually and physically demanding, that you quickly put aside the subjects.

As Barkley observes as we stand before the Lou tapestry, Close's techniques and execution are “a way of capturing something, but also free you up from thinking of these as people. You think of them as images.”

Chuck Close: Prints, Process and Collaboration at MCA Sydney until March 15

For information on the exhibition see: www.mca.com.au

For more on Chuck Close at Elsewhere see here

post a comment