Graham Reid | | 4 min read

If anyone doubts the pulling power of great architecture and design to re-invigorate a city and lure tourists they need only consider one word: Bilbao.

In the Eighties, this city in the Basque region of northern Spain was in economic free-fall: Industries were failing or in decline, unemployment – especially among the young – was climbing and the city of some one million souls was looking like it faced imminent collapse.

And then by series of fortunate circumstances everything was turned around. By happenstance the Guggenheim Foundation was looking for a place in Europe to build a new museum of contemporary art and so went into partnership with the Basque government in '91 to build something special and spectacular in Bilbao.

They invited three leading architectural firms to submit ideas.

The winner, as we now know,

was the innovative Frank Gehry who was renown for his unique designs

such as the Nationale-Nederlanden Building in Prague (dubbed Fred and

Ginger because it looks like dancers, pictured) and the Experience Music

Project in Seattle among many others.

The winner, as we now know,

was the innovative Frank Gehry who was renown for his unique designs

such as the Nationale-Nederlanden Building in Prague (dubbed Fred and

Ginger because it looks like dancers, pictured) and the Experience Music

Project in Seattle among many others.

Two decades ago the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao opened to immediate acclaim (and yes, some critics) for its sculptural appearance, cladding of silver titanium and unusual curvature.

Located near Bilbao's historic district and commercial centre, the museum – much like the opera houses in Oslo and Sydney – came to be emblematic of the city . . . and a city which would now draw more than a million visitors a year.

Its role in transforming the city's fortunes became known as “the Bilbao effect”.

But a breathtaking and idiosyncratic building by the late Zaha Hadid who died in 2016, three years after her building was completed, is a must-see for anyone visiting the city.

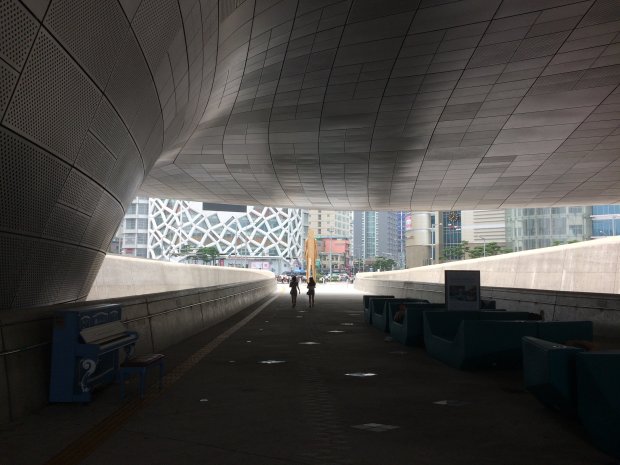

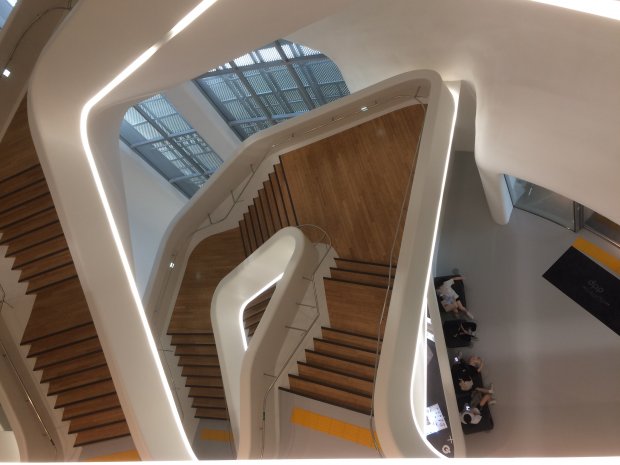

The Dongdaemun Design Plaza aka DDP (“dream, design, play” in its brochures) is an astonishing, huge and uniquely feminine building composed of graceful curves and over 45,000 exterior panels which illuminate at random at night.

It is so large that when you exit from Dongdaemun History and Culture Park Station you don't actually “see” it because it is above and all around you. You are immediately under and in it.

It can take a good 45 minutes to walk around. People invariably stop to photograph its ever-changing shape or walk up the path by the groomed grass hill which covers one part of its amoebic-like structure.

On the same site but in separate buildings are history museums.

The DDP was Hadid's largest work – the site is about 90,000 square metres, the main building has seven levels and there are two floors of car parking beneath – and is among the biggest buildings in Seoul, a city with no shortage of huge structures.

It is also hard to describe and because of its size almost impossible to capture in photos.

But let's try.

Here is a sampling of the many that I took by day -- when it was 35 degrees which explains why so few people are pictured -- and when I felt compelled to go and see it again at night.

It also proof again that great architecture can be very beautiful and a magnet for visitors and locals alike.

It just takes a city and an architect with the courage and vision.

In a previous photo-essay series, Elsewhere looked at the New Architecture of Oslo (you can start that journey here)

post a comment