Graham Reid | | 6 min read

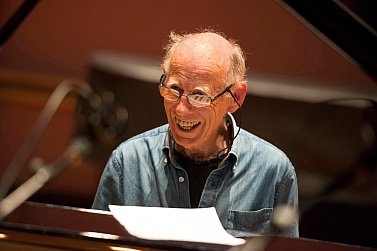

For a man who has spent his life in the earnest art of jazz, Mike Nock laughs a lot, enjoying his deep well of anecdotes, appreciating a joke at his own expense and – when it's suggested a hallmark of his diverse career is that there's no obvious hallmark – laughs until he's breathless.

It's no surprise Norman Meehan's 2010 biography of 83-year old Nock was titled Serious Fun.

Nock spent much of his formative years in Ngāruawāhia, a small town musically, emotionally and culturally distant from Sydney, New York and San Francisco where he made his name.

Yet he maintained strong connections here, returning frequently for concerts and recording albums as diverse as the soundtrack to Geoff Stevens' 1983 film Strata, improvised duets with drummer Frank Gibson on 1987s Open Door, and more recently with the NZTrio, Auckland saxophonist Roger Manins and others.

So, no hallmark.

“I'm not really a jazz musician,” he says despite a shelf of Australian awards and considerable evidence to the contrary. “I'm definitely from that music which shaped and formed me . . . but I'm a white boy from New Zealand,” he laughs, not for the last time in a digressive conversation.

Adding to the many awards in Australia, his home for decades, Nock – made an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit in 2003 for services to jazz – is being inducted into the New Zealand Music Hall of Fame at the APRA Silver Scroll Awards in October.

“Why I'm so happy to receive this award is I think of myself as not so much a jazz musician but just a musician. Period. I express myself in jazz . . . but this is special because it's just a New Zealand music award, a culmination of everything I've been about.”

Despite his cavalier attitude – “Jazz? What does that even mean anymore?” – he has described jazz as “a calling”, imbued with deep personal meaning.

“It goes back to when my father died. I was about 12 and at his deathbed in Ngāruawāhia. I'd been a staunch Catholic, an altar boy and all that stuff, and he died. So my prayers had been to no avail.

“And at that point, I remember it very clearly, jazz became my religion, my calling. And it has been ever since then.

“And why jazz? Because I felt there was an element of truth in the music . . . a certain truth I didn't see anywhere else or in religion. That truth resonated with me and that's been my life.”

As a young teenager with some piano lessons behind him he heard the famous be-bop album Jazz at Massey Hall – legendary players Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and others – on the radio and was smitten.

He thought they were a New Zealand band recorded in Auckland, so different from traditional jazz and pop like band leader Charlie Kunz, singer Winifred Atwell, “a bit of Fats Waller and maybe Duke Ellington” he'd been hearing.

“When I heard that music it really spoke to me, that was how I wanted to play.”

Barely into his teens he joined Johnny Cooper's travelling show around the central North Island: the band was The Fabulous Flamingoes and he worked the door, played the part of a blind pianist (then to the audience's delight would follow a pretty girl around) and play with the talent show contestants.

“I think of myself as a Kiwi Tom Sawyer or a Huckleberry Finn or something, this is the way it was.”

He hoots when saying there would be burglaries in the small towns because when everyone went to the show they'd leave their houses unlocked.

“We were nothing to do with that but it followed us around,” and he laughs long and loud again.

He was getting playing experience and came to Auckland where he backed emerging rock'n'roll star Johnny Devlin. It wasn't his thing though.

“It paid me some money. Not a lot, but in those days it was what I did. I also worked with Johnny O'Keefe here in Australia who was the daddy of rock'n'roll.

“But I could never take it seriously! You kiddin' me?”

To hear Nock tell it, the opportunities always leading somewhere else: he left for Sydney at 18 and after a short period with the acclaimed 3-Out Trio he went to Britain, then took up a scholarship to Berklee College of Music in Boston where he studied jazz and classical music, but not for long.

“I'd spend my time in Australia practicing my buns off on a piano I'd prepared with lead weights because I thought you had to have strong fingers. I knew nothing about sensitivity and touch.”

The scholarship wasn't enough so “I washed dishes to survive, and as a dishwasher the whole concept of America being a classless society was out of the water. I was at the bottom of the class.”

He went to his piano teacher to say he was going to quit but was offered a gig playing jazz four nights a week, a great experience with excellent players and a grand piano.

“And after that I started getting all kinds of gigs and my career started taking off. Maybe it was being a Kiwi and a little cocky I thought I was as good as anybody, I really did.

“I knew there were people who were a lot better because my classmate in the next practice room at Berklee, not playing jazz, was Keith Jarrett who I got to be friendly with and we started playing together. And Chick Corea was asking me for advice a few years later.

“I've known all these players and that's really quite bizarre. I was one of them, “he laughs. “Whether it was warranted or not. That's what it's all about, it's about finding your tribe.”

When Nock starts spinning anecdotes about his long career a roll-call of great jazz names appear, many of whom he worked with or knew as friends: Yusef Lateef, Quincy Jones, Coleman Hawkins, Bud Powell the pianist on that influential Jazz at Massey Hall album, Sonny Rollins who he rehearsed with, and Miles Davis who called him up and said as a compliment, 'I hear you're a motherfucker'.

“True to my New Zealand roots you know what I do, I deny it. It's a game and when someone says that, you say. 'Yeah I am.'

“But we don't do that in New Zealand.”

Davis had certainly seen Nock play in his innovative Fourth Way band of the late 1960s where Nock moved onto electric keyboard, a Fender Rhodes. Legend has it Davis watched them when they opened for his band and, in a much-told story, said to their drummer, “Man, I’m never going on second again.”

Fourth Way – who lasted three years in the late 1960, playing to rock audiences in San Francisco – were in the vanguard of what became electrified jazz-rock of the kind Davis, Herbie Hancock and others were starting to explore, although Nock never saw that as a deliberate direction.

“To be honest it was very pragmatic. I'd been playing piano and it doesn't speak the same way, then I met this guy Harold Rhodes who has this electric piano so I went to Los Angeles and got one.

“The thing was that suddenly I had an equal voice in the band. I was used to playing little uprights and you didn't have the same impact that a horn would have or a vocalist. And the Fender Rhodes gave me that, that's why I gravitated to it.”

Nock was pushing into a new area of sound and style, but once more he moved on because he didn't like the rock context – “I don't get bored there is too much to be interested in” – and wassearching for his own voice.

“I never tried to play like any [other pianist] but it was the spirit of these people that really got me. This spirit of truth and then you start to find out more about it.

“I've never been a commercially oriented musician ever, I always just wanted to express myself the way I wanted.

“I was with [popular singer] Dionne Warwick for a while and when I had enough money to buy my Steinway grand I said I was quitting. She said she'd pay twice the money to stay and I could also open her shows.

“But what I would have been asked to play to open the shows was not the music I was into, I was into doing my Cecil Taylor thing!” he says, referring to the free jazz pianist renown for hammering pianos into submission.

He could probably do that even today. He exercises regularly, is unbowed by a 2018 accident when he was run over “by a 4-wheel drive”, walks with a cane but attends the Centre for Strong Medicine which supports those wanted to live independently.

“I'm still the same, but I'm old. Whaddaya gonna do? You gotta deal with it. I'll be 84 when I come to Wellington [for the award].”

And he laughs again. Serious fun.

These days he plays with musicians a third if not a quarter of his age, records – three typically diverse albums in the past five years from experimental electronic sounds to elegant solo piano – and although not much given to being reflective acknowledges he's been fortunate.

“I've been a reluctant leader [of band] because I wrote. Being a leader is a lonely thing. I never wanted to be 'the best', I always wanted to be part of something.

“I succeeded because I was never the best,” he laughs. “But I've been around all these wonderful musicians and for some reason people have always supported me.

“That's why this [Hall of Fame] award is so wonderful, it's the culmination of a life in music.

.

There are number of album reviews and interviews with Mike Nock at Elsewhere starting here.

post a comment