Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Art Ensemble of Chicago: Suite for Lester

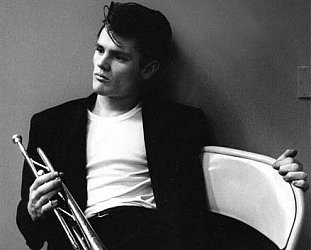

Humour hasn’t had much place in jazz. Certainly Dizzy Gillespie and

Louis Armstrong entertained by mugging things up. But mostly jazz is

poker-faced music played to furrowed brow audiences which think it’s somehow

more morally uplifting than other music.

A couple of years ago Denis Dutton, the philosopher/academic from Canterbury

University, wrote of an anti-capitalist friend in New York who discarded the

consumer society – yet had acquired an extensive and expensive jazz collection.

But, the New Yorker reasoned, jazz is an important modern art-form.

It is. But as Dutton noted his friend could simply have said, “Yeah, but

I like this stuff”.

Dutton's friend sounded an arrogant prick.

Well, jazz does have moments of humour, few more frivolous than a track

on Lester Bowie’s 1992 album All the Magic!, entitled Miles

Davis Meets Donald Duck.

The multi-instrumentalist horn player blew a straw under water and made

it sound like Miles Davis meeting ...

Critics were baffled and some even angry (squandering his talent if not

a few minutes of vinyl), but that was just Bowie having what he called, “serious

fun”.

He did it throughout the 70s and 80s on tunes with titles like Rope-a-Dope

(from Muhammad Ali’s famous phrase) and It’s Howdy Doody Time. In the

late 80s, with his Brass Fantasy band – which often included his wife, the

great soul singer Fontella Bass – he covered Michael Jackson’s Thriller,

the old Lloyd Price hit Personality, Willie Nelson’s Crazy and

Whitney Houston’s Saving All My Love For You.

Bowie’s superb band (which included tuba player Bob Stewart and

trombonists Steve Turre and Frank Lacy) pushed the boundaries of jazz, and

Bowie himself wouldn’t allow them to be pigeon-holed: “Don’t call it jazz, no

way!” he said in 1986, “That word has lost any real meaning. Most real jazz

musicians died penniless, right? So the term jazz to me symbolises poverty.”

Bowie wasn’t poor when he died in 1999 at 58 from liver cancer. He was

well known across the music world – he played on David (no relation) Bowie’s

1993 album Black Tie White Noise – and if anyone could claim to have

changed jazz it was this good humoured, bespectacled member of the innovative

Art Ensemble of Chicago from the mid-60s through to the early 80s.

The AEC – whose members initially wore African tribal costumes and face

paint in performance – were a musical and philosophical attempt to bridge the

divide between ancient black Africa and modernist free jazz. They were the most

visible and influential off-shoot of the Association for the Advancement of

Creative Musicians which formed in Chicago in the early 60s and whose members

included Joseph Jarman, Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre, Henry Threadgill, Roscoe

Mitchell, Malachi Favors and Andrew Hill.

They were inspired by the music of Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman, Sonny

Rollins and Art Blakey.

Bowie arrived in 1966 and famously remarked: “I never in my life met so

many insane people in one room.”

The flexible and political philosophical group became known as the Art

Ensemble and in 1989 the quartet of Mitchell, Bowie, Jarman and Favors had

their hometown name appended for a European show. Percussionist Famoudou Don

Moye joined and for two decades the AEC’s percussive exploratory music – much

of it recorded by ECM whose founder/producer, Manfred Eicher, brought a sonic

clarity to their project – was the benchmark in free jazz.

Their albums Fanfare for the Warriors (Atlantic 1974), Urban

Bushmen (ECM, 1982) and The Alternative Express (DIW, 1989), should

be in any serious music collection.

They slew from primal percussion through sophisticated swing with nods

to Mingus and Ellington, and ride the boundaries of free jazz.

Even before the band split, Bowie had his own swaggering and good

nartured projects playing a melange of funk, r’n’b, jazz and blues which

reflected his early years in Texas clubs and as a session player at Chess

studios.

He called his music avant pop (“Even the term avant garde is old now,

avant pop is where it’s at”) and said to those who accused him of being a

musical gadfly: “All’s fair in love and war – and music is both. So use

anything as long as it works.”

His albums The Great Pretender (ECM 1981), Serious Fun (DIW

1989) and the hard to find The Fire This Time (In-Out, 1992), are his

best, although ECM’s readily available 1988 collection, Lester Bowie: Works

is a good starting point.

Deservedly, former members of the AEC – reed-player Mitchell, bassist

Favors and drummer Moye – came together again to pay homage to Bowie, their

fallen comrade.

Their Tribute to Lester of 2003 wasn’t sentimental, nostalgic or

soft-centred. It was as challenging as the AEC ever were.

Driven from the bottom by an array of percussion which was their

hallmark, this hour-long disc muscles along as Mitchell’s tough tenor scours

through passages or swings over Favours’ dexterous playing. And everywhere Moye

brings tonal colour and angularity from his array of congas, bongos, bells,

whistles and gongs. The 12-minute As Clear As the Sun is demanding

listening, especially when Mitchell turns his sax into a police siren.

Tribute to Lester isn’t a classic AEC album – how could it be with two

men down? -- but is better than we had any right to expect, and reminds of how

this music once was and – in the world of manicured and generic jazz – what it

could be again.

The romantic, slightly baroque Suite for Lester floats on

Mitchell’s sopranino sax and flute then takes off on walking-pace tenor. At

five and half minutes it seems undernourished, but also gets out before any

hint of sentiment invades.

And Bowie was never much for hanging on to the past. He railed against

Wynton Marsalis talking about the tradition: “What tradition? The great jazz

tradition was never copying, right?”

No, it wasn’t and isn’t. It’s about learning, extending and enjoying it.

Like Bowie did.

It’s wrong to speak for the dead but you might guess if he heard this he’d

smile.

The man who knew the meaning of serious fun often did.

mark - Apr 23, 2010

>>>>>But mostly jazz is poker-faced music played to furrowed brow audiences which think it’s somehow more morally uplifting than other music.

SaveUmmmmm, I'm thinking............Yes you are probably correct.

Wait a minute my poker faced furrowed brow is smoothing out and cracking into a smile.

Perhaps the drugs are kicking in.

post a comment