Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Marcus Roberts: Spiritual Awakening

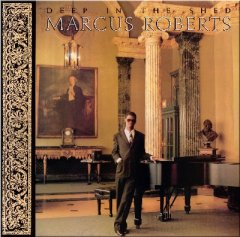

Recently a well known jazz writer, Pete Watrous - not known for his exaggeration - acclaimed Marcus Roberts’ new album Deep In The Shed as “the best jazz album for a decade.”

Put that to 26-year-old pianist Roberts and he laughs (for the first and only time in an earnest half-hour conversation) and starts to sound like Elvis at his most awkwardly modest and tongue-tied.

“Wall, suh,” he says in a

disarmingly charming Southern voice, "I don’t know 'bout that.

I – ah – well, I'm not unhappy that the record has caused people

some enjoyment.”

"Best jazz: album for a decade”

is probably an overstatement but a forgivable one. Deep In The Shield

is an immaculately crafted album which calls on most of Wynton

Marsalis’ current band and fulfills - at last, some would say --

the huge claims made by, and about, this new generation of

neo-conservative jazz players out of New Orleans.

While Marsalis constantly talks of

“trying to deal with the music of Pops (Louis Armstrong) and Duke Ellington" in phrases

which Roberts also echoes (“I’m trying to deal with the blues and

the music of Thelonious Monk and Duke Ellington”) the young blind

pianist has delivered on the promise.

Deep In The Shed -- which comes in a cover of Roberts in a grand room, hardly the woodshed the title implies -- drops somewhere

between the grace of Ellington and the vigour of Monk. It’s a

serious record - then again, Roberts is a serious musician.

Take these comments as a fairly typical

example of his reply to a question about how outsiders are responding

to the growth and development of Marsalis and himself on record.

“It’s very difficult to hear a

record of somebody and understand what exactly it is they are trying

to do and what other artists they may be checking out. It takes daily

contact to know any person, so with Duke Ellington, for example, we

have 50 years of recorded music to reflect upon.

“But I have to wonder just how many

people really understand his music yet. It’s very difficult to deal

with it on any level of complexity because that music is so well

thought out and so sophisticated and complicated it is beyond most

people’s comprehension - including myself.

“You can‘t make any accurate or

definitive statement about that music in any depth.”

Yes. Roberts is a serious character and

sees his own music not simply as a form of self-expression but as

part of an important reclamation of the jazz tradition which was

somehow lost during the past three decades.

“A number of things occurred and certainly the free jazz movement lost touch with an audience. But also the music started being redefined and was taken off the bandstand, commented on and removed from a context.

"Then of course the leaders - John Coltrane, Pops - died and Monk stopped playing. There were no figureheads giving us direction.

“People like myself and Wynton grew up listening to Parliament and Funkadelic but playing those tunes isn’t going to teach you much about playing the piano or the sax or the trumpet.

“You get to meet a lot of pretty

girls and so there are those peripheral and attractive elements - but

they have nothing to do with the serious pursuit of music.“

That determinedly dedicated pursuit has

been articulated frequently (and with monotonous pomposity) by writer

Stanley Crouch who has been carrying the banner of the Marsalis

school of thinking on album liner notes. And he does it again on Deep

In The Shed - specifically placing Roberts at the centre of the

neo-conservative jazz renaissance.

Roberts rests comfortably with that but makes clear the technical gifts and knowledge he has acquired are there to be shared not for self-aggrandisement.

“I have no problem with pointing the

way and helping others but I also have no problem going to people

like (ex-John Coltrane drummer) Elvin Jones and asking him with great

humility for advice.

“If you are going to elevate people

through your endeavours you have a certain balance between

self-confidence and humility."

The idea of elevating his audience -

and reaching out beyond it to others - is a subject Roberts returns

to frequently.

“First we have to make this music

available and try to educate people. They may hear something and want

to pursue it so we should keep that musical option open.

“Just because rap has supplanted the

blues at this point doesn't mean that generations down the line won’t

take these documents (Ellington, Monk, his own recordings) seriously.

“When I play some Monk I'm trying to

give people a sample of, not so much Monk himself, but a music which

can arrive at that same level of sophistication.

“I can’t say, ‘Don't listen to

rap’ but what I want is for any kid of 15 years old in any part of

the world to be aware of John Coltrane or people like that and accept

his music as a valid alternative so he could get out and purchase a

record of it if he chooses. I don’t feel we‘re at that point yet.

I want to elevate and perpetuate high idealism throughout every

culture."

A half hour conversation with Marcus

Roberts is very much like talking to Wynton Marsalis - the same

dedication is apparent, the same themes emerge. Both deflect a lot of comment about

their own music towards the masters they have been "trying to

deal with."

Yet Deep In The Shed is such an

individual statement (more so than many Marsalis records where the

style can be heavily borrowed) that it seems remarkable he first

started playing jazz in public a mere five years ago. He seems to

have come twice as far as Marsalis and found his own voice in half

the time.

With its broad sweeps and subtle septet

arrangements, Deep in The Shade hints at what may be to come -- some

kind of suite in the manner of Ellington perhaps?

"Yeah, yeah - that's it," he

says enthusiastically. "I’d like a record to be a conceptual

statement in itself and I’m moving in that direction now.”

His next album, already recorded,

however, is of Monk, Ellington and Jelly Roll Morton tunes, just

"trying to deal with them."

The clues are better found in what he

is listening to as he takes his own small group on tour - tapes of Duke Ellington’s Far East

Suite and Charlie Parker With Strings.

Roberts may, or may not, have made the best album of the past decade with Deep In The Shed - that’s a matter of opinion.

But for only a second effort as leader

it is very impressive.

He's serious. Time to take him

seriously.

post a comment