Graham Reid | | 17 min read

Ronnie Wickens was one of the last to leave my 50th birthday party at Portside. As I made for the door I looked back, and there he was at the bar chatting to -- maybe even chatting up -- a couple of girls in their 20s, friends of my sons' no doubt. Ronnie was somewhere past 60, but he still looked great.

I don't recall what he was wearing that night but I always think of Ronnie in winklepickers and a sharp jacket, that’s how he was when I was a kid and he came to live in the flat beneath my parents' home in Mt Eden.

At some time back in the very late 50s after my family had settled in Auckland my dad and a friend Brian Henderson dug out underneath our huge home in Kakariki Avenue. They shifted tons of earth, one wheelbarrow at a time.

Into the resulting hole they built a beautiful one bedroom flat which, from the kitchen door looked out across our tennis-court sized back garden between two cypress trees.

The first couple who rented it were Jack and Doris White from London. They became Uncle Jack and Aunty Doris and over the years as various arms of their extended Jewish families arrived from England they too became our family.

There were many others who passed through that flat and whose friends became ours, like the tall, thin and scrupulously moustached Ted Dolores who owned a well-known hair salon in town and brought his friends from television and the fashion world around.

And there was Ronnie, a ship steward who wore stylish clothes like drape jackets and shirts with button-down collars, hosted beautiful models, and had a jazz collection.

My bedroom was above Ronnie’s back door and every now and again I’d get a waft of some ineffably cool jazz: the woody sound of a tenor saxophone, the deft brush of drums, the walk of a dark bass. It was a long way from the pre-Beatles pop of Cliff Richard or Big Bad John that I was listening to on my transistor.

At some point, and I can't even remember when or how, the Dave Brubeck Take Five album came my way and I played it over and over on the large gramophone in our lounge. I assimilated every nuance of it, every weaving melodic line by saxophonist Paul Desmond on Blue Rondo A La Turk and every tricky turn of a beat by drummer Joe Morello.

I have always associate this kind of sophisticated music with Ronnie.

It must have been about 1961 and was just after that time of beatniks and berets which Mad magazine was still parodying. My sister's boyfriend Warwick, now her husband, was what I thought a beatnik was. He had the small beard and was called Mario -- as in Lanza -- on account of having sung at a party.

This was the time when the height of hip was a straw-wrapped Chianti bottle covered in slow-dripped multi-coloured candle wax. My sister had one.

The Tab Hunter Show, Donna Reed and Gerry and Sylvia Anderson’s pre-Thunderbirds shows Supercar were on television. At night I'd listen to the weak comedy of Life With Dexter and dark thrillers from Randy Stone’s Nightbeat on the radio. And Dave Brubeck was on my turntable. I was about 10.

It was the tune Take Five which, in an instant, made me understand what jazz was all about. It was simple really -- they made it up as they went along. It was instant invention, a music where the player was also the composer. You could hear it in every precise and considered note of Take Five.

Saxophonist Desmond -- who wrote the piece -- establishes the simple, memorably melodic theme over a Brubeck's repeated piano figure and Morello’s bantam-weight drum patterns. Then, just after a minute in Desmond takes it on a flittering flight, drawing the notes out, dropping them into the gaps between Morello’s drums and the punctuating bass of Eugene Wright. All the while Brubeck keeps the repeated vamp going before Desmond drops out and Morello’s drums rise into the foreground two minutes in.

He discreetly adds fills then, abruptly and with a thump of the bass drum, changes the direction completely, rattles off machine-gun like staccato before a huge bass kick which seems to be entirely contrary to what Brubeck is still diligently playing beneath. From Morello’s kit comes a series of small rhythmic explosions before he indicates he is signing out by pulling back, and about 45 seconds from the end Desmond again enters playing that memorable theme, its sinuous melody ending in a lovely bird-like breath.

It is a remarkable piece of music, elegant and poised, and behind its difficult 5/4 time bassist Wright holds it all in place like a counterweight.

As the liner notes say on my battered CBS Coronet copy, 'and contrary to any normal expectation -- perhaps even the composer's! -- Take Five really swings'.

It was also a whistle-able hit. We’d pucker up and do it at Scouts when we hiked up from Swanson station to our camp site in the Waitakeres.

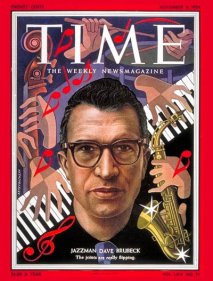

I wasn't the only one who found jazz via the Dave Brubeck Quartet. The man made a fortune on the back of Take Five and was -- I learned much later -- embraced by college kids across the States and Europe. To his embarrassment he was on the cover of Time magazine 1954. Critics said it should have been Duke Ellington there representing jazz. Brubeck agreed.

The geeky white guy with the Buddy Holly horn-rims who looked more like a biology teacher than a jazzman was always subject to derision by jazz critics who considered his music bloodless and academic, middle-class and buttoned down.

The influential New Yorker critic Whitney Balliett wrote Brubeck off in 71 after he appeared at the Newport Jazz Festival: 'He is what he is -- a jovial amateur pianist who happened along at the right time with the right music and made a million.'

Jazz critics -- a role I have sometimes played but never relished -- are notoriously snooty, partisan and prone to playing favourites. The worst sin for a musician in the eyes of many jazz critics is to make money in jazz. For some reason they see that as selling out, arguing the music must have somehow been diluted for it to succeed in a world of philistines who simply could not understand this music in its purist form.

That's all arrogant bullshit of course, and elitist jazz critics are often the music and the musicians worst enemy. They bewilder the curious with a barrage of names and musical lineages which close doors rather than open them, they acclaim the arcane and obscure, and decry the successful like Brubeck.

It was hardly the pianist's fault he was on the cover of Time -- that is an argument critics should have had with the magazine's editors not the hapless musician who found himself cast as the face of jazz -- and it seems peculiar that those who would pretend to best advance the music would be condescending to an audience.

Okay, they were white college kids moving on from Sinatra bobby-sox pop to smoking pipes and trying to look cool, but they might just wade in deeper waters in years to come. And by their interest they would support this minority music which needs all the friends it can get.

I guess that's where I came in.

Brubeck's entry level Take Five was certainly of its time -- just as the icy intellectualism of jazz on the German ECM label in the early 80s caught the imagination of white graduates who had become comfortable with cool Miles Davis and were now looking for something different. But Take Five also reaches across the decades.

In the early 80s I was teaching English at Glenfield College and my students and I were talking about Jack Kerouac's On the Road and the Beat poets. Most of these 17-year olds said they just didn’t get jazz.

Fair enough, Duran Duran and Springsteen's Dancing in the Dark were big at the time. But most were also honest enough to admit they hadn't actually heard any jazz. So, to get into the rhythms of Kerouac's sax-driven prose, I thought I should play them some.

I knew exactly where to start, with the piece which explained it to me.

And then I took them on a distilled version of the journey I had been on ever since those days around the family gramophone where, within two years, Brubeck was being eased out by Beatles and Rolling Stones singles.

To be honest, I didn't listen much jazz -- other than Brubeck and a little Miles Davis -- during my grammar school years. The Beatles, Stones, Hendrix and Jefferson Airplane had won me by then. Jazz just seemed dull and difficult, and somewhere else.

I never walked away from jazz entirely however -- my Dad played Louis Armstrong and With The Beatles back-to-back -- but there is a lot of it I don't like: men in straw hats playing banjos; self-obsessed jazz-rock fusion; and women singers who don't improvise but emote heavily through the most meaningless of lyrics.

I understand why the musicians do all this, I just don't like it.

The jazz which gets me is the free flowing stuff: the sound of a saxophone or trumpet turning a melody inside out to find new meaning, the drums and bass beneath which propel this journey into the unknown. There is excitement in this, a sense of tension and discovery about it.

The thrill is in the unexpected drop of an octave, the whiplash of a drum which changes the emphasis and emotion, the weeping glissando of the bass.

There can be drama, real human drama, here, not something faked to be parlayed into a career like you hear in contemporary r'n'b and pop.

Like when tenor saxophonist John Coltrane played the dramatic and elegiac Alabama, recorded in November 63, as he reflected on the bombing of a church in Birmingham, Alabama that September by white racists which killed four black children.

Or when Dexter Gordon accompanied the dying Billie Holiday, his former lover, in one of her last television appearances when it is obvious her days, eroded by unhappiness and drugs, are clearly few.

Yet it needn't be a big name player like Coltrane or Gordon at the helm.

That's the thing about jazz, it can also be about playing favourites. Your belief in an artist can be vindicated by a single performance, or you can simply stumble on someone whose music speaks to you. As I did with Andrew White in the early 80s, a tenor player about whom I knew nothing (black, American, influenced by Coltrane, damn good) and still have only the one album by: Passion Flower from 74 on his own Andrew's Music label.

I came to Andrew White's album by a circuitous route courtesy of Auckland multi-instrumentalist Jim Langabeer whom I met some time in the early 80s.

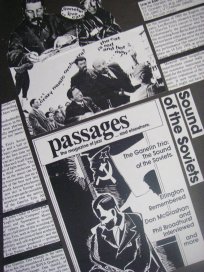

In 1984 I created, edited, subbed and often wrote much of, my own magazine. It was called Passages: A Magazine of Jazz and Elsewhere.

In its pages we -- myself and a team of faithful, unpaid but enthusiastic writers -- covered Thelonious Monk, Count Basie, touring artists such as Sanguma from Papua New Guinea who played tribal jazz, local musicians by the dozen, and the then-new ECM label out of Germany with all its icy elegance.

As that 'elsewhere' in the title suggested, we also covered and critiqued new music from New Zealand: notably adventurous local stuff like From Scratch, music from the Wellington Braille collective such as the Primitive Art Group, things by Auckland guitarist Ivan Zagni (Avant Garage, Big Sideways) and much more besides.

We were trying to put this music into a greater context than merely review it. It was a magazine -- put together at nights on my dining room table after a day teaching at Glenfield -- which had more subscribers in Poland than it did in Wellington. It folded after 11 months.

It had grown out of my association with the Auckland jazz promoter Pat Shaw, an enthusiast and idealist who ran the monthly Cotton Club concerts in the 80s at the now-demolished Mandalay Ballroom in Newmarket.

Pat ambitiously brought in touring artists -- the legendary pianists Art Hodes and Sammy Price, saxophonist Benny Golson and many others -- and together we put out a Cotton Club newsletter for his patrons. It grew into the Auckland Jazz News and then, far too ambitiously and too early for our time, Passages.

At some point in 84 while editing Passages I heard about some innovative free jazz from the Soviet Union on a label called Leo run by a Russian émigré Leo Feigin who lived in London.

These recordings, all of which had the thrilling cachet of being smuggled out of the Soviet Union, sounded fascinating so I wrote to Leo and bought some from him (all in sturdy, monochromatic Soviet-style covers). Then Jim Langabeer and I decided to import a swag and see if we could sell them through Passages.

The deal was simple, Jim had his own small music import company, I had the pages of Passages in which to promote and advertise them. And so we did it.

Passages devoted many pages of analysis and astute interpretation to these pre-glasnost albums -- Why the Soviet Union? Why now? And so on -- and waited for our readers to flood Jim with orders.

Needless to say, it didn't happen although both Jim and I have copies of these extraordinary free jazz albums and the knowledge that we knew about them long before they gained more widespread attention in the late 80s.

It was through Jim's small company Musaid run out of his home in Glen Innes that I discovered Andrew White's Passion Flower. Jim had brought some in and flicked me a copy to listen to, a quartet recording made in Maryland of all places.

After some melodic throat clearing on the title track ballad it kicks in with the fiery New Blues, a 15 minute piece of scorching, muscular and rapid tenor magic. I remember playing it one night to my friend Guy Allen, also a teacher at Glenfield College.

He didn't like it as much as I did, but then again Guy knew a lot more about jazz than me. For me 1967 had been the year of Sgt Peppers, he knew it as the year Coltrane died.

My growth in jazz I owe to Guy more than anyone, other than Ronnie Wickens who unwittingly set me on this path. Guy opened me to a world of music which I have never tired of exploring.

It was Guy, four years older than me but decades ahead in wisdom and knowledge, whose large and dangerous jazz collection held numerous temptations.

Through him I discovered politicised black free jazz of the late 60s and early 70s and musicians with fabulous names like Jemeel Moondoc, Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre and Longineu Parsons.

Sometimes we’d smoke a joint and immerse ourselves the tribal angularity of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, hoot with laughter at twisting sax lines and punctuating farts from baritone saxes, marvel at how Miles Davis could take his trumpet for a skate on ice as thin as a wafer, or slap our knees and try to keep time with oddball rhythms from drummers like Jerome Cooper or Ronald Shannon Jackson.

Guy would tell me stories about eccentric Thelonious Monk who would walk all night after a gig to a friend's house for some of his mother’s cake then leave without a word and wander off into the dawn-dripping streets after he’d eaten it.

And of being seated on the stage when Sonny Rollins played at Ronnie Scott’s club in London.

Best of all Guy -- who incidentally didn't rate Brubeck at all other than as someone who got white kids into jazz -- turned me on to the composer and multi-instrumentalist Ornette Coleman whose music I came to love with a passion.

I would borrow Ornette albums from Guy -- we always referred to him by that magnificent and singular name -- then I embarked on my own buying spree. I scoured second-hand shops for slices of old vinyl which I would turn up with remarkable regularity. Ornette became my project, I wanted to hear every note he had played.

Randolph Denard Ornette Coleman was born in Fort Worth, Texas although the date is variable: some say March 1930, his sister Truvenza says the following year. He was largely self-taught and played tenor sax in a few local r’n’b groups. He took to the road and got stranded in New Orleans, was given a touring gig which lead him to Los Angeles, and at age 30 started studying musical theory.

He barely worked because his style was so unorthodox but by the late 50s he'd established a band and Contemporary Records put them in the studio. Ornette and his bands started releasing albums with prescient and provocative titles: Something Else!, Tomorrow is the Question, The Shape of Jazz to Come, Change of the Century …

Until he, surprisingly, came to New Zealand in 2008 (for which I wrote the programme notes) I had never seen Ornette play but I had passed my passion forward: my son Julian went to a concert in London for his 33rd birthday, it was also Ornette’s 75th.

But I had met Ornette Coleman in New York City in mid 96. It was then, and still is now, the highpoint of a career in music journalism during which I have interviewed such notoriously grumps as John Lee Hooker and Neil Young, sparred with Miles Davis and come out of it unscathed and proud, tried to talk with polite say-nothings like BB King, endured mouth-spouters such as Meat Loaf, been reduced to laughter by a couple of Motley Crue morons, and had a nice conversation the mainsprings of Led Zeppelin Jimmy Page and Robert Plant.

But Ornette was The One, and the one who made me feel the most nervous.

The night before, sitting on the ill-sprung bed in the cheap Off Soho Suites in downtown I read again through my notes, over and over.

My partner said, "Look forget about it. If you can't have an intelligent conversation with him no one can. You know his stuff backwards."

That was reassuring, although it didn’t stop me having two quick coffees the next morning as I sat in a diner in the garment district around the corner from the photographer’s studio in which I was to meet him, and where he also owned an apartment.

My brief fantasy was that we'd really hit it off and he’d invite home for lunch or dinner or a drink. Guy would be spitting.

I walked around the corner, the doorman let me in, I stepped out of the small elevator at the photographer Austin Trevitt's studio and the door opened: there he was. Ornette Coleman.

He was dressed in a blue checked suit with buttons up the sleeves and around the scalloped lapels, in a vivid purple waistcoat and a collarless shirt buttoned up to his neck.

He was smaller than I imagined, but also so much bigger.

I started my profile for the Herald like this: "For a man who has had his lights punched out, was reviled by critics and audiences, often ignored and, in latter years, belatedly recognised as a genius. Ornette Coleman is remarkably slight.

"Even with his hat on he hardly nudges above average height and his fine frame and barely audible voice wouldn't seem to pose much of a threat. Yet Ornette Coleman has been on the flat end of a fist or two and his critics have been legion."

We talked for an hour, a free-ranging conversation in which he sometimes said things which didn't make much sense. This is him on interpretations of his music by the fashionably hip downtown composer/musician John Zorn: "As a composer how can you know what something you haven't done? How can anybody do something they haven't done? That’s real democracy, isn’t it? If someone asks me has someone done it better than I've done, I can't hear it because it hasn't been done, I haven't done it myself."

It sort of makes sense now, but certainly didn't at the time. I nodded. A lot.

By this time of his life Ornette could reflect on a remarkable career: he had recorded with a symphony orchestra (the Skies of America album) and numerous string sections, played in Morocco with the Master Musicians of Joujouka, in a loft in the early 60s with the pre-Lennon avant-garde singer and Fluxus artist Yoko Ono, and performed at the White House for Jimmy Carter. His aphorism at the time I spoke to him was typical: Remove the caste system from sound.

More than anyone I have heard Ornette -- who prefers the description "composer" because it allows him to work in any idiom -- has done exactly that. I have albums where he plays with rock musicians, and another of a single, 40 minute composition written in honour of Buckminster Fuller played by the Gregory Gelaman Ensemble.

Ornette's aphorism also means to not acknowledge a hierarchy of instruments: no lead instrument with a drum or bass simply being supportive. All instruments are equal and can improvise simultaneously. He calls it his "harmolodic system" and no one says it's easy to understand, best just to let go and enjoy it when it's happening to you.

As on the bouncy 3 Wishes with Grateful Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia which kicks off his Virgin Beauty album, probably the most listenable poppy album in his enormous catalogue. The music infiltrates the ear, winds its way into the subconscious as it tickles along. It is music which is beyond analysis, it just is. And it is very Ornette.

It was a terrific interview -- I still have the tape, the only one out of thousands I have ever kept -- and it was one of those rare occasions when I had my photo taken with the musician I was interviewing. Photographer Trevitt snapped off a few images and said he’d send them to me later.

I couldn't wait to tell Guy.

There are dozens of Ornette Coleman pieces I love, but one in particular comes to mind now as I sit at my desk, the photo of Ornette and me on the floral couch in a frame to my right.

The piece is Faces and Places, recorded live in Stockholm in during a Coleman Trio fortnight-long residency at the Golden Circle in late 1965.

It is a lively piece, Ornette's alto sax bores its way into an unusual melody while drummer Charles Moffett rapidly tickles his cymbals and bassist David Izenzon pulls out huge punctuation marks before the trio takes off with Ornette leading the way. He frequently returns to a phrase to centre himself in the 11 minute piece which is best described as "rocking" for its relentless forward momentum. His astringent alto bites into the spiralling melody, lifts it away from its roots for a while, then wrestles it back. Someone -- Izenzon at a guess -- lets out exuberant shouts which inspire Ornette into further flights. You can hear his schooling in the tough sound of the Texas r'n'b tenor players, elements of the blues are scattered like shards of flying glass.

Coleman, who had largely been absent from playing live for three years at this time, sounds inspired, throwing himself headlong into the music, dodging and weaving as he changes tack, but never lets the energy drop, never sounds like he has worked himself into an emotional or musical cul-de-sac.

It is a thrilling piece, full of life and urgency -- and I never hear it without thinking of my friend Guy, and how he brought me to this place.

In 2004 I was at the Caravan of Dreams in Fort Worth, Texas, Ornette's old hometown. The Caravan was designed as a multi-purpose arts centre and Ornette opened it in September 83 with a series of concerts with his electric band Prime Time and the Forth Worth Symphony Orchestra. Removing the caste system from sound, I guess.

As I sat in the rooftop bar I thought how Guy would never get there and I had a beer for him. I had grown up on the pop music of my day, but Guy had opened a door to something else and took me through with a map and torch in hand.

We arrive at music in unusual ways sometimes: the sound of it drifting up from a flat below your bedroom; an album by an unknown artist passed on by a friend; an encounter with someone at work who can introduce you to something you know exists but have never had the confidence to explore.

I came to jazz through all of these, and other unusual, ways.

At Guy's funeral two years previous -- where he had requested they play the vibrant, life-affirming and defiant Face and Places -- I had been asked to speak. I don't remember what I said -- something about how can you miss someone who will never go away, I think -- but I did thank him for taking me deeper into jazz which has become a central part of my inner life.

And for leading me to the prismatic, adventurous music of Ornette Coleman.

phil johnson - May 19, 2009

thanks, I really enjoyed reading this after happening on it by chance while googling beatles plus ornette to try and see if any of the fab four had attended ornette's UK debut at the fairfield halls in 1965 for a story I'm writing about ornette's meltdown.

SaveI loved your interview story - I've only done him by phone, where he didn't make much sense either - and also the bruneck mad magazine beat parody stuff I remember too

there's a UK jazz musician called dave wickins....

keep up the good work

phil johnson

post a comment