Jeffrey Paparoa Holman | | 4 min read

On a day in September 1972 in my mother’s house at 11 Franklin Street, Greymouth, my father shuffled across the room in his dressing gown and broke down in my arms.

He had just been delivered his death sentence by Dr Kibblewhite, who had then left quietly and driven away.

The cancer treatment was not working: Dad was told he had perhaps a couple of weeks and then he would die.

Cradling my sobbing father – when what I really wanted was for him to cradle me – has haunted me ever after. This became a poem in 1973 and, twenty years later, another writing of the same event when the seed lines of a poem I called ‘As big as a father’ ambushed me in the bathroom of a London council flat.

How do we react when told point-blank that the death we all know awaits us is about to arrive, is on the doorstep, knocking? My father sobbed on my neck, grieving for his losses, choking, ‘My life’s been such a bloody waste!’

‘No, Dad,’ I shot back at him, ‘no it hasn’t!’

I still don’t know how convincing I sounded – even to myself.

Memory is tricky,

but I did try to console him, struggling with my own anger: What the hell was I doing being a parent to him?

Memory is tricky,

but I did try to console him, struggling with my own anger: What the hell was I doing being a parent to him?

Again?

Ask any adult child of an alcoholic how this weird reversal comes about and they can explain – but I didn’t know any of this back then.

All I knew was that as his life collapsed around us, I couldn’t stand to watch – but I had to.

Was this really the man who had terrorised me and my family late at night: home slamming doors from the pub in Blackball, muttering to himself beyond the cracks of light glowering beneath my bedroom door as I pulled the sheets over my head, me listening to my brother swearing to kill him, my sisters waking in the next room, screaming?

Was this the man who had spent six years on active service in World War Two, a signalman and later a chief petty officer on huge aircraft carriers fighting the Germans and the Japanese, mythical figures who haunted the imagination of a boy born and raised in the shadow of the war?

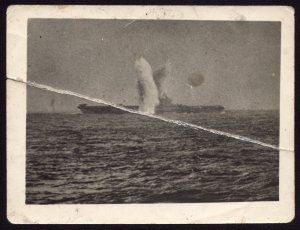

The same man who had seen a kamikaze flying straight at him in April 1945: diving for cover as its wing sliced through the radome on the bridge of HMS Illustrious, plane and bomb falling and exploding together in the waves beside the ship, just missing him and his shipmates?

Lying with them flat on the signal deck, parts of the Suisei dive-bomber and its two-man crew showering down, scattering in smithereens onto the armour-plated flight deck as the great ship, shaken like a wounded beast, surged on through the seas off the Sakishima Islands?

Yes, this was my father – the man who had faced death as his paid employment, surviving to die twenty-seven years later in a hospital bed, with me just down the corridor.

Dad was in the final stages of physical collapse and surrender; my malady was more mental and spiritual, the emotional burnout of watching my monster, my former hero, die.

The more I studied that picture over the years, the more I began to wonder who were those men that had attacked him that day, why they died and my father – and I in my father – lived; why they vanished, their sons and daughters never to be? How was their death sentence experienced and lived until that terrifying moment: from the hour they first knew they were chosen to die for Japan and the emperor, until black death swallowed them in fire and madness as the Allied ships rose up to meet them out of the shining sea in a storm of anti-aircraft fire?

Far from being the suicidal fanatics of Allied wartime portrayals and later comic book caricatures that I was weaned on, I would discover that these men were just like my father: the majority were young, aged eighteen to twenty-four, many of them university students, the educated flower of their country.

They were the kind of men who could not stand to hear the clocks ticking the seconds away in their final nights and so smashed them; men who got drunk on sake, slashed light fittings in their barracks with samurai swords; some of whom were Christians, singing forbidden hymns, wrapping up bibles to carry with them on those flights to human oblivion.

Men like him, yes, and men like me: complex and precious human beings.

This is the story of my search for my father and his enemies. I do not know at the point of writing this sentence where it will lead me. Like any journey worth taking, like any day we rise up and follow the path the sun takes until it passes over, the act of setting out is enough to begin with.

What can we possibly learn from men who saw themselves as "sojo no koi" ("carp on the cutting board"), live fish awaiting the stroke of death in the midst of a ruthless, titanic struggle that threatened to obliterate any prospect of human choice and individuality?

Yet even in this extreme situation, courage and its poetry survived the madness.

So now I must go in the hope of meeting at least one of them and their relatives, of paying my respects to the living and the dead.

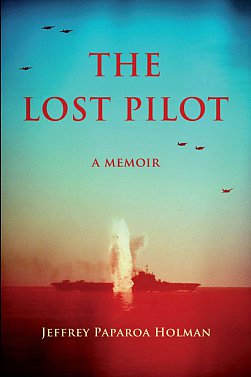

Reproduced with permission from The Lost Pilot by Jeffrey Paparoa Holman. Published by Penguin Group NZ. RRP $40.00. Copyright © Jeffrey Paparoa Holman, 2013. Copyright © images Jeffrey Paparoa Holman, 2013

Jeffrey Paparoa Holman is an award-winning Christchurch-based poet, novelist and non-fiction writer who lectures in English at the University of Canterbury.

His Best of Both Worlds: The Story of Elsdon Best and Tutakangahau, was published by Penguin in 2010. This non-fiction work delves into the 1895 meeting in the rugged Urewera ranges between Best, a self-taught anthropologist and quartermaster, and Tuhoe chief Tutakangahau, which would have lasting effects on our views of traditional Maori society.

For more on this remarkable memoir The Lost Pilot and his other books go here.

Other Voices Other Rooms is an opportunity for Elsewhere readers to contribute their ideas, passions, interests and opinions about whatever takes their fancy. Elsewhere welcomes travel stories, think pieces, essays about readers' research or hobbies etc etc. Nail it in 1000 words of fewer and contact graham.reid@elsewhere.co.nz.

See here for previous contributors' work. It is wide-ranging.

post a comment