Graham Reid | | 5 min read

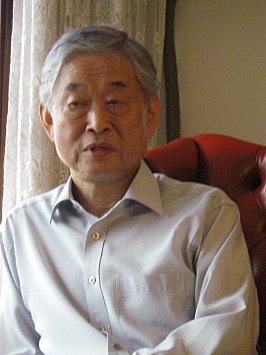

Byungki Hwang: Sounds of the Night Part 4, from the album Kayagum Masterpieces, 2001

In Seoul, the vibrant capital of South Korea the old and new, the raw and polished, frequently rub together in odd juxtapositions. So a butcher’s shop with pig trotters on the wet floor is perhaps to be expected in the suburban street where the country’s most famous musician lives.

Byungki Hwang, at 72 when I visited him in 2008, was still Korea’s leading player of the traditional gayageum -- a unique stringed instrument. As a young man he learned this wonderfully evocative instrument and almost single-handedly rescued Korean court music and folk songs from being lost after the battering his country took during the long Japanese Colonial Period, the Second World War and finally the Korean War of the early 50s.

Which might make you think the home of this living legend would be in one of Seoul’s more swanky suburbs.

Of course inside the gates of Hwang’s home the atmosphere is very different.

Upstairs he enjoys a commanding view across low-rise apartments to the office towers of modern Seoul. Here is a happy clutter of books and paperwork, and shopping bags of CDs (Brazilian guitarist Laurindo Almeida and Western classical albums among them). Piled-up texts and manuscripts spill across the massive low table in the centre of the room.

The Korean gayageum -- sometimes spelled kayagum -- is a wooden instrument almost two metres long: it has at least 12 strings (sometimes as many as 21), moveable frets on the soundboard, and the strings are plucked by the right hand while the left depresses them to create microtones, bends of notes or gentle glides.

Tradition says it was based on an ancient Chinese instrument in the 6th century but it is unique in north Asia, a point the professor is quick to make.

“The gayageum is of the zither family,” says Hwang as he sits on the floor with one resting over his crossed legs. “But it has its own special characteristics which make it different to the Japanese koto or Chinese instruments in the same family.

“The koto is played on the floor and the Chinese instruments are on a table, so they are outside the body of the musician. The gayageum is played with the fingernails and we hold it close to the body so it becomes part of the player’s flesh.

“In many ways the gayageum is the core of all Oriental string instruments. But of course Korean music is the most unknown music in the world,” he laughs.

Hwang -- of sprightly appearance and dry wit -- is unfortunately correct and his observation comes from long experience. Despite touring internationally he still, almost invariably, plays to predominantly Korean audiences, even at Carnegie Hall or in Paris.

The reason that Korean traditional music is largely unknown outside the country is because the West experienced Eastern music through its colonial contacts: Britain heard sitar music because the Empire dominated the Indian subcontinent; gamelan music from Indonesia made its way to Europe through Dutch colonists of the region; Chinese music seeped out through the cultural hotbed of Shanghai; the French discovered the music of Vietnam through their occupation of Indo-China . . .

But Korean music got no further than Japan, its colonial occupier.

“And it is one of the most difficult music for Western people, Korean gayageum music doesn’t use harmony -- and there can be very little ‘crossover music’, as people call it, using Korean instruments.”

Where Ravi Shankar could take sitar music to Western audiences through collaborations with Yehudi Menuhin, Philip Glass and others (not to mention his friendship with George Harrison), gayageum music remains on the margins of Western awareness.

That is a pity because the restful, earthy tone of the instrument, the dramatic ripple of fingers across the strings, and the stately sound of Korean court music melodies can be quite beguiling. When the heart and ears are open very little is lost in translation.

The fusion-gugak movement of the mid 80s brought traditional instruments like the gayageum and janggu (hourglass drum) together with electric bass, guitar and keyboards, but it is often bland and jazzy saxophone solos or MOR rock guitar can’t disguise the fact most fusion-gugak sounds emotionally empty -- not an accusation you could aim at Hwang’s intense music.

In 1951 when in his late teens and the Korean War was still raging across the peninsula, Hwang began studying gayageum in Busan (also written as Pusan). With the encouragement of some master musicians he started researching Korean traditional royal court and folk styles. Not an easy undertaking: the Western classical tradition had arrived in the late 19th century and Korean music was no longer taught in elementary schools.

In 1951 when in his late teens and the Korean War was still raging across the peninsula, Hwang began studying gayageum in Busan (also written as Pusan). With the encouragement of some master musicians he started researching Korean traditional royal court and folk styles. Not an easy undertaking: the Western classical tradition had arrived in the late 19th century and Korean music was no longer taught in elementary schools.

Traditional music was associated with ruralism, poverty and the past, so Hwang encountered indifference from audiences more keen to hear Western classical music which was associated with sophistication, modernity and knowledge.

“I tried to meet some of the Royal Court musicians, who were by then in their 50s, and found out as much from them as I could, and also found the music they could pass on.

“The court music was for upper class people and some was written down, but the folk traditional was purely oral. I had to learn it by ear from people who still played it.”

At the time Hwang started his studies the Korean National Assembly passed a bill establishing national music institutions to preserve the traditions of Korean music, and in 1959 the Seoul National University founded a college of music.

Hwang’s career ran parallel with these developments: he became a performer, archivist and teacher; wrote music for films and television in the early 60s; toured internationally; and when he was only 26 rather daringly began to compose for gayageum.

“In former times there was no concept of a composer or composition, gayageum music was not ‘owned’ by anyone so no one put their name to a composition.

“I am the first who composed for the gayageum by using written manuscripts and Western notation. My colleagues were surprised and probably a little embarrassed,” he laughs.

His first composition Forest created a new genre of Korean music, ch’angjak kukak or “newly-composed Korean traditional music”. Later he experimented with changes in tuning and used unconventional playing techniques. Today his once-controversial works are part of the standard repertoire for gayageum students.

Hwang is considered a living treasure in his homeland although -- despite touring internationally, being a visiting lecturer at the University of Washington in 1965 and visiting professor of Korean music at Harvard in 1985 -- he and Korean music remain unknown by most Westerners.

Yet he is an amusing and articulate advocate for this meditative, restful and often sublime music. He still tours and his recent collection The Best of Korean Gayageum (Arc Music) has international distribution.

Korean gayageum music may not be familiar in the way Japanese koto, Indian raga or Javanese gamelan music have become, but Hwang is an acclaimed master -- and a local hero to gayageum makers.

“When I began to learn gayageum in 1950,” he says, his eyes glittering as he anticipates his punchline, “there were only about a dozen gayageum sold in a year. There are 10,000 nowadays.”

And at that Professor Byungki Hwang allows himself a very broad smile.

Here is a man who quietly rescued a national music . . . and that's exactly why we need to talk about the extraordinary Byunki Hwang.

.

Byungki Hwang died a decade after this interview, in 2018

.

For other articles in this series of strange, interesting or different characters in music, WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT . . . go here.

George Klales - May 25, 2009

I lived in korea for three years as a peace corps volunteer. During that time I studied the language and culture and learned some of the pop songs of the time (1971-1974). Regrettably, I never learned much of the traditional music. Recently I have been listening to kayagum on youtube and I find it very beautiful and restful. I would like to buy or build a kayagum and learn to play.

SaveI would give my right arm to study with someone like professor Hwang. Fortunately he has a legacy that will last through his students and manuscripts. The fact that so many kayagums are made each year also ensures that an art that surely would have died, now lives on for those who craft these instruments.

This article is very interesting but I find it strange that Professor Hwang's age is listed as being 62 and yet his study of the kayagum started in 1951 in his late teens.

Graham of Elsewhere - May 25, 2009

ha! 62!!! i can spell but not add, i've made the correction -- he was of course 72.

Savethanks

G

Soh-Hyun P Altino - Feb 16, 2024

Thank you for this beautiful piece. I just happened upon it, and it warmed my heart. The short kayagŭm piece is delightful. I appreciate Hwang's insight regarding traditional Korean music and ache for the fact that it is still not much better known around the world than it was when you interviewed him. I agree with you -- we need to talk about traditional Korean music more. If people can get to know it and understand it, they might even enjoy it. Thanks again. https://www.sohhyunparkaltino.com/home

Savepost a comment