Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Etran Finatawa: Iledeman

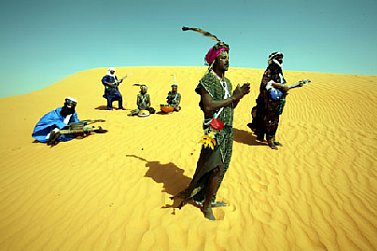

Etran Finatawa have band members from two nomadic groups from around Niger, and play music which sounds like the raw electric blues from Chicago in the Fifties and Sixties. Their electrifying music is tough, but full of yearning. It may have a hypnotic quality which conjures up the open spaces of their region, but it also rocks mightily.

Their debut album Introducing Etran Finatawa stormed the world music charts and, along with Tinariwen from the same region, threw the spotlight on this unique sound of African blues.

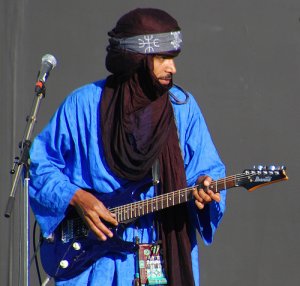

Singer-guitarist Alhousseini Mohamed Anivolla talks to Elsewhere . . .

How was the first contact made between the Wodaabe members and the Tuareg members of Etran Finatawa?

Most of the Tuareg and the Wodaabe come from the same region in the northwest, next to the town of Tchintabaraden. They used to stay at least a couple of month in the capital, where they would meet. I was friends with [singer-guitarist] Ghalitane Khamidoune, the bandleader, and also with some Wodaabe people and actually they used to meet on my terrace. Ghalitane had a Tuareg band (Etran N´Guefan) and the Wodaabe had a dance ensemble (Finatawa). Both groups got a separate invitation for the Festival of the Desert in Mali in 2004. For that trip they prepared two songs to present together. It was a success and when the two bands came back from Mali we decided to work together. After some month of joint work we created Etran Finatawa.

When members of each people began to play together what was the music you discovered you had in common? Folk songs? Or did you start writing new songs straight away?

At the beginning we actually mixed songs, traditional or modern songs that were already there and written or we arranged traditional songs like Ronde or Anadjibo on the album. But after a year we started to write new songs, new creations with both elements in it and sung on both languages, like A Dunya and Surbajo.

The traditional dance songs with handclapping or just the percussion have some similarities in both cultures. Apart that the music is very different in both ethnic groups. The Wodaabe have their way of polyphonic singing that is unique, and the Tuareg use more instruments and have a different way of poetry as well. It was a lot of work and it still is to combine these two styles, and also keep the particularity of each style.

How aware were the various members of Western music - music like the blues from America, pop and rock music from Europe and America?

Music from Europe or America is not so much known in Niger. Rap is known and there are many young rap singers. People like music from Mali, they like to listen to Ali Farka Toure, Oumou Sangare, Salif Keita, Habib Koite and of course Tinariwen. There are many Tuareg bands, and people like to listen to their own music. Now as the members of Etran Finatawa travel a lot they get to known many artists from Europe and America and like to listen to it. People like John Lee Hooker, Femi Kuti, Angelique Kidjo, Bob Dylan and so on

Is the music you make -- even though it uses electric guitars -- still quite traditional? Do the older people like it?

Is the music you make -- even though it uses electric guitars -- still quite traditional? Do the older people like it?

There are modern arrangements and traditional songs. Some people like it, others don’t. Tuareg music has been modernised by guitars since the late 70s. For the Wodaabe, Etran Finatawa is the first band where Wodaabe people make modernised music. Some elders are very traditional and are against it, but most of them are happy to see that Wodaabe people and Wodaabe culture has had such success.

Have you been criticised by either Wodaabe or Tuareg elders for the kind of music you make? Or criticised by each people for playing with members of another people?

Of course the very traditional people don‘t like it. But many people see in Etran Finatawa a symbol for that the times are changing, and peace and coming together. When we made our first tour in 2004 to the countryside to Wodaabe and Tuareg camps people were very happy to see the two tribes making music together. It was always underlined that this is the right way and they are encouraged to continue.

How has your music changed since you started touring in Europe? Have you started writing songs in a different way?

I think all members of the band are much more professional, they have seen how other musicians arrange their music, how they react on the stage. They work much more now on a song, see the importance of rehearsing. This is more professional and less traditional. We started with two composers now four are composing, all of them got inspired by other musicians. Music for them became not only a way of showing their culture but also a way to communicate with the world about their life, their culture, their problems. And Etran Finatawa has realized that more than at the beginning since they started touring.

I think they became real ambassadors of nomadic culture and that is a kind of their mission as well.

Some of the songs on the album -- like Aliss and Iledeman and Anadjibo -- sing of division and problems: some personal, some tribal and some between religion and tradition. You live in a very troubled region, what is daily life like for the people of the desert. Do they still retain their traditions or is it changing?

Life is changing so much these years. The rupture began in 1974 with the first drought. Before nomads were rich, since then they became poorer and poorer and are now the underdog of the Niger society.

Desertification pushes people further south or even into the cities as environmental refugees. The traditional way of life guaranties less and less a survival. Rupture is a central scheme in their songs as in their life.

Islam became much more important in Niger and in their life as before, the way of clothing is changing, modern life came to the nomadic societies, tourism is getting more important.

People love their traditions and their way of life in the desert in harmony with the environment and the animals, but it is becoming harder and harder and they are under constant pressure and fighting for survival. Malnutrition, diseases, fights for water and grassland is a constant factor in their daily life.

The young people go to the cities and try to survive with little jobs. In the cities they loose their traditions. That is one reason why we created Etran Finatawa. As their culture is their richness and it is worth being practiced not only in a folkloric way in hotels for foreigners, but as a way of communication. Etran show this richness and appreciated their culture. They are proud of being nomads, they fight against discrimination. They use it, live it and work with it. Their culture now gives them their daily bread and people all over the world get to know about Tuareg and Wodaabe culture and its richness that is worth being appreciated. I think that is very important.

Africa is not only poor people!

post a comment