Graham Reid | | 8 min read

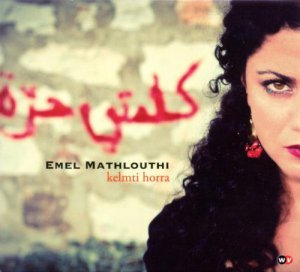

Emel Mathlouthi: Kelmti Horra/My Word is Free

On December 17, 2010 a 26-year old street trader Mohammed Bouazizi, sick of police harassment and confiscation of his wares, set himself alight in the street outside the police station in Sidi Bouzid near the Tunisian capital of Tunis.

His sacrifice touched a raw nerve in Tunisia, a country riven by corruption, and riots ensued. The revolution to overthrow the government had begun, and in its wake other oppressed people around the region followed and took on their own corrupt governments and authorities.

The Arab Spring – waves of civil resistance, protest and the fall of governments – had begun.

In Tunisia the protest movement found its anthems and sympathetic songs in Emel Mathlouthi, a protest singer who had moved to France but whose song Kelmti Horra/My Word is Free written by Tunisian singer Amin al-Ghozzi spoke to and for the people.

Other songs of her (notably Ya Tounes

Ya Meskina/Poor Tunisia and Yezzi/Enough from her album released in

January 2012) also captured the mood of sadness coupled with

optimism.

Other songs of her (notably Ya Tounes

Ya Meskina/Poor Tunisia and Yezzi/Enough from her album released in

January 2012) also captured the mood of sadness coupled with

optimism.

When Emel Mathlouthi, who has lived in France since before the Tunisian Revolution, appeared at the recent Womad – and delivered a wonderful and uncompromising set (see here) – Elsewhere took the chance to speak with her about her life in Tunisia, the protests and her current music.

When you were growing up in your early

teens, what was life like in Tunisia? What access did you have to

outside cultures, like rock'n'roll?

It was quite boring to grow up

as a teenager in the capital Tunis which was the best place to be in

the country. But I got lucky because I discovered rock music, metal

music actually. Like many many people in the world, it saved me.

It's interesting that metal is the one that does it. I've spoken with Blend who live in Beirut and they said there was a very big metal scene there. What was it about metal that attracted you?

I don't know. I started with pop-rock and the first band that attracted me was the Cranberries because they were quite protest musicians, and also Sinead O'Connor. I really liked their vocals.

Then there was something about the energy of metal at that age, and more so when you are in these kinds of countries when you are looking to burn everything around you. (laughs)

And just listening to records – we couldn't buy CDs and there were no places to listen so it was somebody somewhere who got something on the internet, the older brother of a friend of a friend of friend . . . this was how I started listening to Deep Purple, Led Zeppelin, Janis Joplin . . .

That music appeals to teenage energy.

The energy and the soul. There was a soul in this kind of music and also in the metal of the Nineties. That was the last great period of rock music for me. Rock now has to be melted with other things. The spirit of rock should still exist in the new music of today, but with other elements.

But also it was very deep music. When you listen to Patti Smith's vocals you feel completely different to what is being done today.

Was there for you a sudden political awakening for you, or was politics always talked about in your home?

I think I was ready, I was ready to say no. I think I had a big character since I was very young and I needed to raise my voice, especially when I went out to play with other kids. My mum would say she would have to listen to only my voice when I was outside with other kids. (laughs)

At home we would have to stay quiet because we were four children and I couldn't be different from my brothers and sisters. Even in school you had to be like everyone else so you start building your own world inside you.

When you started singing political songs, what sort of places were you singing in?

The first place was an NGO, I think it was Nelson Mandela's NGO and it was launched by an Indian lady and they adopted me very fast. At that time I was just playing guitar and doing covers of Joan Baez and Bob Dylan and the other American artists. That was my first audience, and for me it was a dream because I really felt we were in another sphere. We were far away from a very ugly system and we were building a revolution.

You felt optimistic at that point, that

a change was going to come?

You felt optimistic at that point, that

a change was going to come?

Yeah, I always felt I was very strong when I was performing and maybe this was the thing that gave me the strength to write my own songs about the same subjects, because when was performing Baez and those songs in the Arab world with guitar instead of oud, I really felt I was powerful and felt hope. I had a goal.

What age did you leave Tunisia and was

there something specific that prompted that?

I left when I was 25.

There wasn't one incident but it was obvious I had to go. At the

beginning I just started performing with my first band – a metal

band – and when we started doing concerts and rehearsing I only

touched the things I wanted to do. So to me it was obvious I had to

leave so I could do what I wanted to do 24 hours a day.

At some point when I started writing and performing my own songs under my own name with my own band I did quite interesting things at that time which were very important first steps, which helped before going to France. Because I had already started writing the songs that I would perform in France.

After a short time when you see no one is helping you, you can see you can't raise your voice in the media and can't participate in a festival even if you are good, so you are going to fight and lose a lot of energy and just bump into walls

You had been recording in Tunis before

you left the country?

I started recording live concerts and the

first time I recorded in a studio was in a friend's house. In one

afternoon I recorded eight songs and the day after we mixed and I

added the backing vocals. Then I worked on the cover because I was

studying graphic design and then I printed it. That was my first

production and I sold it after my concerts, and that helped me

because I sent it to some contacts in France.

When you got to France your music was banned back home?

It wasn't officially banned, they weren't really concerned about this growing scene but radio couldn't play the music of course. I got some invitations twice to participate in a television show but they started by telling me what to sing. 'We know you are smart and good but just sing a very common song.'

But you can't sing anything else because everybody is going to have problems, not only you but the programmer and everybody else involved. Same thing at radio.

The first people who listened to Kelmti Hora said, 'You are crazy, what are you singing about?'

Did they think it was dangerous for you to sing a song like that?

Yeah, of course. But I was laughing about that. I didn't feel threatened at any moment and also because I was living in France and working with French partners, so that was some protection.

Were people saying it was bad for your career or that it was dangerous.

Both actually. I got some support from some good journalists who wanted to speak about things I was singing about, so some of them gave me some interviews and asked me why I chose that when I could sing lighter songs. Or I could go to Lebanon and become a star. But I said I didn't choose anything like that, this was just the way things were, it was my destiny.

Were you were away when the revolution happened?

No, I was actually in the country. I was performing for the first time outside the capital. I had two concerts and one of them was in Sfax which is very close to the south of Tunisia. There on about December 23 2010 we started hearing about what was going on, that somebody burned himself and strikes were taking place.

So I was I think the first one who sent a message on stage and there were some youth there. I had problems with the organiser because he was scared it would make problems for him. They told me before the concert to not sing any protest songs but I talked with the musicians before and we said we were going to go and do them, because you couldn't really do anything else.

You must have felt that this was the big change you'd been waiting for in Tunisia?

Yeah, but when you are doing music you don't really think about anything else, you feel very powerful and hopeful and have so much nice feedback from the audience you think, 'It's going to happen right now'.

Have you ben back to Tunisia in the past three or four years to perform?

I go back but it's not very easy for me to perform there. Once the revolution happened they put all the small young singers, the protest singers active on social media, in the big festivals that refused me for years. I tried to push the doors open and would submit my application but they never looked at it.

Why?

Then because they can't put out that music before the revolution. After the revolution, the 2011 year, they could and they programed me everywhere. And after that, nothing.

So the system didn't really change, especially for culture, music and art. But the civil society is growing very fast and some cultural movements are taking place . .. but they don't have the support because there are old minds still there, the same people.

I want to ask you one last question. You sang a new song here Saleem and you said it was about giving up. I'm at a disadvantage because I don't know your language, so I'm curious about what you were singing there.

When I say, 'give up' it's very cynical. I push to shock and be cynical, so it is the opposite. The thought started from living in Tunisian society, and even in general society, because the society and traditions and general thoughts around you want to take all that you have, all your dreams, your thoughts, your innocence. So I just wanted to put a focus on that.

We don't really talk about how people suffer and are lost in a society, and we say these people are crazy or depressed. But it's just that our societies are very severe and if you are a bit too sensitive or a bit artistic you are attacked in different ways. So you could just give up.

Yes, so it's also a questioning of course. In the chorus I say, 'how can I close my eyes and sleep when life is full of thorns?' because people become like thorns around you.

It's remarkable song, and that's going to be on the new album?

Yes. The first album you could say was political because it was about freedom and I still feel concerned about different things and they too are important. And I also have another song about homeless people.

You asked if we had homeless people here.

Yeah, because I didn't see any here or in Adelaide.

The guy next to me said, 'Not many' and I just thought he doesn't live where I do because there are certainly homeless people here.

Yes, and people in the audience protested and said, 'No, there are'. Maybe they are pushing them to places where you can't see them, and that is worse. What I mean by this song is that when I look at people in France they pass the homeless people by, even if it is an old lady sitting there.

Of course everybody can give money, but the first thing is that people need to be sensitive to it. They just get used to homelessness and they walk away

For more details on Womad 2014 artists with sound samples and Elsewhere's opinion simply go here.

.

.

post a comment