Graham Reid | | 4 min read

While diplomats and ambassadors exchanged platitudes and gifts in August 1992 to acknowledge the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ first voyage to the New World, others found little to celebrate at all.

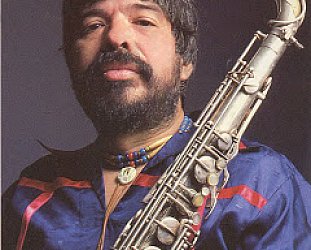

John Trudell, a Santee Sioux who was spokesman for the Indians of All Tribes Occupation of Alcatraz in 1970 and was for six years from 1973 national chairman of the American Indian Movement, understandably saw the arrival of the Italian navigator in a different light.

Articulate, good-humoured and measured in his response, this poet turned high-profile recording artist with his recent Aka Graffiti Man (sic) album doesn’t even entertain the notion of the anniversary being an opportunity to re-evaluate the history of the Americas.

“Among indigenous peoples, we don’t need to re-evaluate. This predatory energy arrived on our hemisphere 500 years ago and there’s only one evaluation...it has been genocidal and destructive to all living aspects of the hemisphere.

“And that behaviour has not changed at all; it still continues on its destructive path.

“Many indigenous peoples will protest this anniversary and tell their truths. I haven’t found many people in the circles I move in who endorse it or find anything to celebrate.

“Personally, I think Columbus was like a virus symbolising a diseased spirit which lived on in the thought processes and mindset. This disease must be cured and that will come from our consciousness and respect for ourselves. The virus feeds off people if they are insecure and afraid. You can have a proud people but that doesn’t mean they respect themselves. It can be a mask.”

Trudell’s poems and songs come from his unique – and tragic – history which saw him emerge from the reservation and spend half his formative years in mainstream American society yet always return to the sense of community among his people which he says he hasn’t seen in “that geographical or sociological form since.”

Navy duty during the Vietnam era alerted him to what he calls “the programmed racism” in American society when he, along with other Service people from minority groups, was a target of jibes and ridicule. Drawn into the American Indian Movement in the early 70s, he quickly became a spokesman because of his oratory skills which he channelled into verse in ’79, initially as a form of therapy after his wife, children and mother-in-law were killed in an arsonist’s fire.

His first work was set to traditional drums but a meeting with guitarist Jesse Ed Davis in ’85 “gave me the compulsion to rock the words.”

By the Colmbus anniversary he had issued five albums of poetry, published a number of books under his own name and had been much in demand as a speaker on Indian human rights and Earth-consciousness issues. He had also acted – most notably in Michael Apted’s Thunderheart, which starred Val Kilmer and Sam Shepard. He was interviewed at length in Apted’s Incident at Oglala documentary and his role in the AIM campaign for indigenous rights is recounted in Peter Matthiessen’s book In the Spirit of Crazy Horse.

In the past year Trudell has enjoyed a larger forum in which to give voice. It comes down to his new album a blend of his spoken word/speak-sung lyrics delivered over an R’n’B backdrop provided by the likes of the late Kiowa guitarist Davis. Produced by Jackson Browne, Aka Graffiti Man began life as a rough tape which made its way into the hands of musicians such as Midnight Oil’s Peter Garret (who had Trudell and band open for his group in the States in’88), Kris Kristofferson and Bob Dylan (who took to playing the tape before his concerts).

In the course of Browne’s reproduced version, Trudell deals with domestic violence, Rockin’ the Res (the reservation, delivered with a Stones-style riff), Bombs over Baghdad and Rich Man’s War.

His reputation has long been secure among the cognoscenti - Bonnie Raitt calls him “probably the most charismatic speaker I’ve ever heard,” and the FBI apparently keeps a 17,000-page file on this activist-cum-singer – but the album allowed him to be keynote speaker at this year’s New Music Seminar in New York and see his name appear in the populist rock press, getting to a larger audience than his political and poetic activities had previously allowed.

Understandably mistrustful of the traditional political processes, Trudell says he hasn’t fallen into cynicism.

“There are times when I can be, but overall I’m fairly realistic I’ve learned we shouldn’t be afraid to think what we really think. We should think our truths as best we can.

“Through my writing and now recording – I can speak my truths unhindered by the processes. If others can identify with them, then we are not as alone as we think we are.”

Looking back on the occupation of Alcatraz, Trudell says he recognised then that Native Americans’ demands opened up a bigger agenda than politicians were then, and by implication now, prepared to deal with.

“We had no expectations at all, we just went for it. We were young and America handled it how it would handle it. The majority of citizens had no quarrel with us, so the American Government, through the manipulation of the media, tried to turn that tacit support against us.

“We were threatening to the Government because America is supposed to be about democracy and freedom and respect for the rights of the individual – but if America were to respect the rights of indigenous peoples, then other citizens would want their rights respected too.

“People truly thinking and taking responsibility is the biggest threat to that predatory mind set.”

On Aka Graffiti Man he gets into such matters on “Somebody’s Kid: “Me and Hesus trying to keep loose, keeping ahead of the goose-stepping goose, new age world in an old age cage”, and over a traditional chant and drum on Beauty in a Fade he looks at the skewed relationships between men and women which also revolve on a power struggle.

Yet this child of the extended families on a reservation on the border of Nebraska and South Dakota says it is important to recognise Native Americans are of the here and now, part of the post-Elvis baby-boom generations who share common experiences with more mainstream American society. On Baby Boom Che, about being in “Elvis’ army,” he talks of the split between the generations that the Presley phenomenon drew out.

“There are many things we all have in common in this industrialised culture and are affected by the same information from television. People want us (Native Americans) to look a certain way but that denies us our present and therefore denies us a future.

“But we will come through. It’s the wearing away of the stone.”

post a comment