Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Din Mohammad Zangeshahi: Ya Ghows

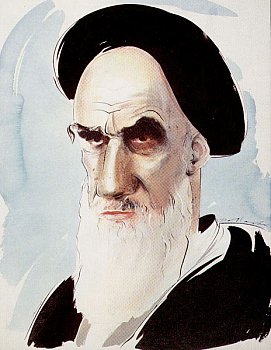

Within weeks of Ayatollah Khomeini returning to Iran in 1979 after almost 15 years in exile, the Islamic Revolution he had envisioned and agitated for was complete and a ruthless, fundamentalist theocracy had been installed in Tehran. One of the many strictures imposed was the banning of Western music which the clerics saw as a corrupting influence.

When asked by an interviewer if that meant banning Bach and Beethoven, Khomeini replied that he didn’t known those names.

Given that in exile he listened to the BBC news assiduously that seems unlikely, but not entirely impossible as this highly readable account of his life and legacy illustrates. Khomeini was a man from another century and indeed a very different world.

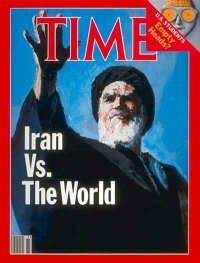

Although seldom spoken about today, Khomeini -- who died in June 89 -- was one of the most pivotal figures of last century and the radical Islamic revolution he helmed based on Sharia -- and a particularly narrow reading of certain texts -- created a schism between radical Islam and the liberal, secular values of the West.

Where once politics or nationalism had been the dividing line between global spheres of influence, with Khomeini it became religious. Fundamentalist Islam would be the banner under which many would, and still do, gather and define themselves.

Khomeini’s return Iran was all the more remarkable because he was 76 when he took power and for most of his life he had been an anonymous cleric and scholar who was considered outspoken and a nuisance, but not a real threat to the increasingly oppressive regime of the Shah.

Khomeini’s transition from religious leader to political force was gradual but as journalist Coughlin traces here, it was conducted with skill, quiet cunning and unswerving dedication. Khomeini’s worldview might have been narrowly focused -- establish an Islamic state then export the idea -- but its impact resonates today.

Khomeini grew up as Ruhollah Musavi in the remote and obscure village of Khomein, his relatively wealthy family could trace their ancestry directly back to the Prophet, and his early life was marked by blood feuds and the presence of religious zealots. The larger backdrop was a country where the anti-cleric Shahs had a history of political expediency when it came to selling out to international forces. Despite the encroachments of modernism and the 20th century, many people were still primitive in their beliefs.

When Khomeini returned in triumph a pious old woman in Qom claimed to have seen his face in the moon. Within days millions had taken to the streets celebrating the apparition and the most devout insisted criminals and bastards wouldn’t be able to witness his lunar presence.

What many who celebrated didn’t take into account was that charismatic Khomeini and his followers wouldn’t usher in democracy (with religion on the margins) as they expected after the flight of the Shah, but the formation of Revolutionary Guards -- every bit as merciless as the Shah’s henchmen in SAVAK, his security police -- and a weeding out of dissenters.

The world around Iran had changed also: the Realpolitik of Henry Kissinger had given way to the liberal, moral agenda of the weaker US president Jimmy Carter who had called on the Shah to adopt a more accommodating regime. Into this political uncertainty and vacuum stepped Khomeini and his loyalists.

Khomeini quickly established absolute authority and began building connections with a global network of Islamists. That, argues Coughlin, is his legacy: Iran’s nuclear programme (which Khomeini initially opposed as a manifestation of the Shah’s Westernisation of the country, then backed fully); support for the emerging Hezbollah and Hamas organisations; and the export of terror (Iranian extremists were behind numerous attacks and assassinations, or provided organisations such as Hezbollah with support, in places as far afield as Berlin and Buenos Aires).

Today the events that defined Khomeini’s regime have faded: the hostage crisis in which revolutionaries held 52 Americans for 444 days during which time the US looked increasingly impotent; the bloody and futile war with Iraq in which thousands of Iranians died; the fatwa declared on Salman Rushdie . . .

But the network that Iran’s Islamists built up in the years under Khomeini and his hardline successor Ali Khamenei (a loyal ally and cleric) still exists, although the world around Iran -- and within it -- has changed yet again.

Today journalists such as Gwynne Dyer argue Barack Obama needs to engage in a different kind of dialogue from the hectoring and bullying that was a hallmark of the Bush administration. There is the belief Iran is able and willing to engage in meaningful dialogue with the West despite its anti-Semitism and truculence.

Others say that the outward reaching, former Iranian president Mohammad Khatami for example -- who recently visited Australia and is often characterised as a reformer -- is simply the benign face and diplomatic silver tongue of a regime which remains evasive in its international relations and transparently insincere.

As with most countries in that troubled and problematic region, Iran can be read many ways but it cannot be understood without considering its recent history.

However you look at it, the political parameters of the world today are very from what they were when many Iranians welcomed Khomeini back from exile and -- mostly unwittingly and perhaps increasingly unwillingly -- recalibrated the relationship between the Islamic world and the West.

As this compelling, topical and sometimes contentious analysis shows, two decades on from his death Iran is a country which owes a much greater philosophical, religious and political debt to Ayatollah Khomeini’s particular world view and his 10 year reign than we in the West might think.

post a comment