Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Emmanuel Jal and Abdel Gadir Salim: Ya Salam

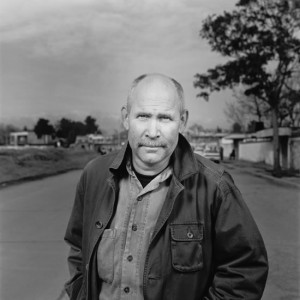

The old man emerges from a halo of half-shadow, golden light catching his white beard, pinpoints of sun creating white flares in his penetrating eyes.

Like an Old Testament prophet or a portrait from Rembrandt, he seems to come from beyond time.

“It was late afternoon and we were in one of the big forts with mud walls,” says photographer Steve McCurry. “Low light came in and hit us. I saw this guy with a biblical look about him and it just made sense.

“A lot of times you can anticipate how a portrait or a scene will look. I knew that would be an amazing photo.”

Amazing photos are the forte of McCurry, a member of the Magnum group since 1993 and whose career has taken him into war zones and mean streets around the world.

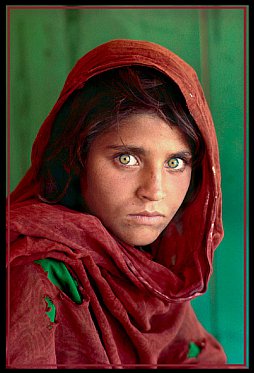

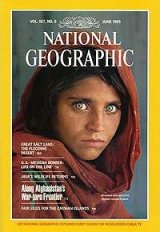

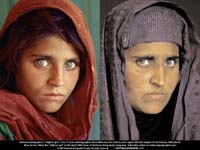

His most well-known photograph is of an Afghan girl taken in a refugee camp in 1984. The following year the image of the 13-year old, her penetrating green eyes staring unwaveringly at the viewer, was featured on the cover of National Geographic.

It became the most recognised image in the magazine’s history but the girl was anonymous and efforts to locate her again proved fruitless -- until 17 years later when McCurry found her and took another photograph.

That photograph with resonances of Rembrandt also came from time in Afghanistan four years after he first photographed “the Afghan girl”, now known to be Sharbat Gula.

That photograph with resonances of Rembrandt also came from time in Afghanistan four years after he first photographed “the Afghan girl”, now known to be Sharbat Gula.

It is one of 250 photographs taken over a 20 year period until 2000 -- unfortunately without explanatory comment -- in his remarkable collection Portraits.

Here is a sleepy-eyed Tibetan baby wrapped in swaddling clothes sharing page-space with a suspicious, shaven-headed Chicago punk, an old woman from the hill tribes of Burma with her neck elongated by brass rings juxtaposed with the image of a holy man from Haridwar in India covered in ashes.

They are extraordinary photographs, although McCurry downplays them with the characteristic modesty of someone who has survived the fire-fights and civil unrest which have erupted across the planet.

“The whole concept of the book was accidental,” he says. “Richard Schlagman who runs Phaidon Press was planning a book on India and we got together to look at my work, and he got excited about all the portraits.”

The publisher’s enthusiasm is understandable because McCurry’s photographs penetrate beneath the surface and he uses the subject’s eyes, always engaging the camera, as a barometer of the soul.

“If I see somebody’s face which interests me -- whether it’s something of beauty or shows someone’s experience or pain -- I kind of confront the person. I really want to look into their eyes because they can tell you of the happiness, sadness, fortitude, perseverance or innocence.

“I want to get inside the person and the best way is to have them confront the camera and the viewer.

“I think it’s instinctual on my part, maybe some longing inside me which wants to connect with other people.”

At 50 when his book was published, McCurry had enjoyed and survived a remarkable career in photo-journalism. A graduate of Pennsylvania State University’s College of Art and Architecture in ‘74, he first worked as a photographer on Today’s Post before embarking on a freelance career which took him first to India, then into rebel-controlled Afghanistan in ‘79. His images of the Russian invasion were published around the world.

He covered the Iran-Iraq war, photographed while under fire in Beirut, Cambodia, the Philippines and during the first Gulf War, and he recorded the disintegration of Yugoslavia.

He covered the Iran-Iraq war, photographed while under fire in Beirut, Cambodia, the Philippines and during the first Gulf War, and he recorded the disintegration of Yugoslavia.

He has accrued dozens of awards including numerous from picture-of-the-year competitions, awards for excellence from press associations, and individual acknowledgment from magazines such as Life and Time.

Some of his work was also included in the handsome Magnum Degrees collection published in 1999 to celebrate its 50th anniversary.

That McCurry has survived is testimony to his skills, smarts and preparation.

“I don’t do anything rash until I understand the people, how they’ll react to the camera, and the risks involved. I get a gut felling of what I’m getting in to.

“Then, if you are careful and use good judgement, you are able to do a lot. If you get into a zone of concentration or understanding the ebb and flow of the situation, you’ll be okay.

“I’m almost always with a local person I trust and whose judgment I value. I look on his face and gauge my chances. It’s sort of intuition and going with your instincts, and all the incoming -- whether its mortar rounds or rockets -- is random to a point.

“But you can get a sense of when to back off and when to go forward.”

McCurry says that confronted with the chance to save a life in battle or capture the image he has no doubts about what he would do.

“The whole point is to have some positive effect and that gives you the justification for pointing your camera into a dying person’s face. Journalism and witnessing events is important, but faced with the choice the first priority is to help somebody.

“It depends on the situation however. If you are in a famine in Africa the big picture is probably more important than passing out candy bars. But if there was a situation where it is pulling somebody from a flaming wreck in Rwanda or Bosnia, it would be hard to live myself if I thought I could have saved somebody’s life but rather I took a few frames of film.”

And what has McCurry learned about Mankind after the carnage and cruelty he has witnessed?

Two things: the resilience of people and how they can normalise a situation (“even when they’ve had a leg severed or lost a family, they are in time able to bounce back”); and that “people are generally the same whether in Afghanistan or Brooklyn, Bosnia or Burma -- we all want respect and much the same things.

Two things: the resilience of people and how they can normalise a situation (“even when they’ve had a leg severed or lost a family, they are in time able to bounce back”); and that “people are generally the same whether in Afghanistan or Brooklyn, Bosnia or Burma -- we all want respect and much the same things.

“If you approach people in a small village in Yemen with a smile, they respond the same way somebody in New York would, yet they are worlds apart and might as well be on different planets.

“Human nature is much the same everywhere. You can be under gunfire in Kabul surrounded by Islamic zealots with crazed looks in their eyes and hell-bent on going to Paradise if they are killed, and think these are horrific conditions.

“But when you are in that, things seem pretty normal and if you pick up the camera people have the weirdest reactions, even when bombs are raining on them

“What keeps me going is that I love exploring the world, and the unpredictability of the lifestyle of travelling around.”

Of course it isn’t all mad militants and grinding poverty, sometimes he gets to photograph Angkor Wat for a National Geographic photo-spread.

“Yes, and that’ll be very contemplative, peaceful and quiet. A very interesting change of pace.”

post a comment