Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Less than a year after he had what the designer of the Sydney Olympics 2000 closing ceremony called “the biggest one-man show in history”, the artist known as Reg Mombassa was part of a group show in Wellington.

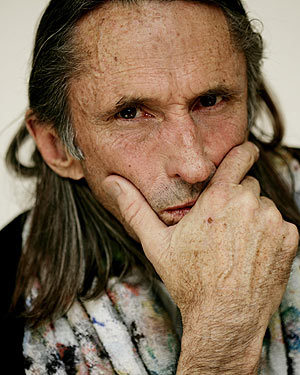

For Sydney-based Mombassa -- born Chris O’Doherty in Auckland in 1951, and founder member of the Australian rock band Mental as Anything -- it was an amusing come-down.

He may have commanded a global audience of four billion with his huge, inflatable Australian Jesus, Frankenstein Kangaroo, Beer Monster and other characters at the closing ceremony (“Macy’s Parade on LSD,“ said Ann Gerhardt of the Washington Post), and had successful solo exhibitions in Sydney . . . but Wellington?

Not one of his 10 pieces in Bowen Galleries sold.

“But I don’t have much profile in New Zealand,” he laughs, “partly because I haven’t made the effort -- apart from a couple of little shows.

“The Mentals were a bit popular, one album did reasonably well. And Mambo,” he says, referring to the Australian clothing label for which he created distinctive designs.

“So I was unknown. You’ve got to be there and turn up, and I didn’t do that stuff.”

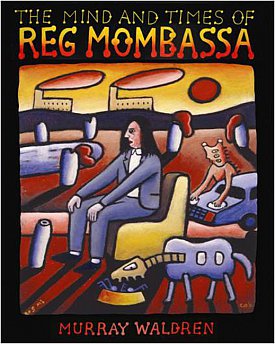

In music and art, Mombassa created his own path without doing “that stuff”, but is now the subject of a lavishly illustrated book The Mind and Times of Reg Mombassa by Murray Waldren.

“We’re promoting it as the first of its kind in the history of the universe, because it’s a biography, art book and popular culture book in one.

“It’s like a de facto history of Mental As Anything and Mambo, as well as the art and music scene in Sydney through the years . . . a cultural history of a period.”

It is also about him growing up in and around Auckland, the booze and violence of teenage males (“it’s always dangerous for young boys, you’ve got to be lucky to survive”), being bullied at school, finding refuge in art, and feeling a “skinny, unattractive, fairly untalented outsider” before he went to Australia in his late teens.

Yet while creating irreverent and sometimes politically-fuelled Mambo work he would frequently return to his fascination with childhood homes and the semi-rural landscapes on the periphery of Auckland, imbuing his paintings and drawing with an emotional calm and undeniable nostalgia.

“Coming [to Australia] meant that childhood seemed further away in space and time. I was living in the inner city too, different to Auckland’s outer suburbs. “Those works have a feeling of a different life and culture -- and reflecting on the family in those tiny black’n’white photographs, there was a stillness about them.”

When O’Doherty settled in Sydney he moved through heroic drinking and a bohemian lifestyle, art school, post-punk bands and finally Mental As Anything where he adopted the name Reg Mombassa during a typical bout of silliness.

He continued to paint and draw (charcoal and coloured pencils) while touring with the Mentals, designed posters and album covers, and drew landscapes with odd aliens and surreal animals, peppering them with Dada juxtapositions and religious symbols.

In 1984 Mambo approached him and his idiosyncratic designs for Mambo clothing became as recognisable in Australia as Keith Haring’s were in New York: but if Haring commanded a city, Mombassa‘s were adopted by a country.

His Mambo work was wry, satirical, often laugh-aloud, and sometimes socially or politically provocative.

While he numbered Patrick White among

those who collected his gallery art, the wit of Mambo impeded

critical acceptance. He concedes he wanted attention from the serious

art world but his gallery shows -- often sell-outs -- were rarely

critiqued.

While he numbered Patrick White among

those who collected his gallery art, the wit of Mambo impeded

critical acceptance. He concedes he wanted attention from the serious

art world but his gallery shows -- often sell-outs -- were rarely

critiqued.

“When I say I’ve been ignored that’s not entirely true, [but] I think a lot of critics thought, ‘He gets enough attention anyway and doesn’t need more’. Or that I just had t-shirts.

“But good graphic art is still art.

“You do shoot yourself in the foot by being a buffoon and using humour. It was the same with the Mentals, they’re not critically well regarded because we were seen as a slightly wacky, lightweight pop band.

“If you don’t take yourself seriously it’s hard for other people to.”

While the art-school Mentals (their most familiar song If You Leave Me Can I Come Too) went for the big picture -- albums, tours of Australia, the US and Europe, group showings and painting a Melbourne tram -- much of Mombassa’s work is small.

He attributes that to his father asking him to do some pieces for a doll house and enjoying the challenge; Mentals touring meaning he could only carry a sketch book; a modesty of purpose; and recoiling from “pompous, alpha males making energetic canvasses“.

“Small painting has just as much impact if you get up close, it is still taking up a large acreage of your visual perception.”

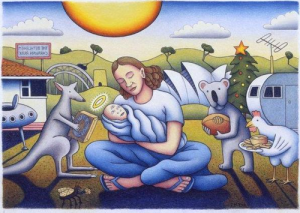

Although now identifiable as a signature style, Mombassa’s early work drew from the hellish visions of Bosch, Breugel and Goya (mutated into bright cartoon form) and into this are fanciful animal-like creatures (mad dogs, frantic chickens), and spacemen and rocket-ships from 50’s sci-fi comics.

He pulled in religious imagery such as

his Australian Jesus which outraged some and amused many more. (Mambo

Faith: Australian Jesus at the Football: The Miracle of the Pies and

Beer, 1996).

He pulled in religious imagery such as

his Australian Jesus which outraged some and amused many more. (Mambo

Faith: Australian Jesus at the Football: The Miracle of the Pies and

Beer, 1996).

“I’ve been interested in religion. People seeing spacemen or the Virgin Mary is all much the same, hallucination or seeing things deeply. I’m fascinated by these arcane belief systems.”

He repeatedly returns to drawings of landscapes and houses however: “Those simple, suburban, cheap and ordinary houses which were just nice, plain and simple Fibrolite or Weatherboard, brick sometimes, homes.”

Comfortable such paintings may be, but some have smoke-puffing factories on the horizon which, Magritte-like, have a menacing presence.

Mombassa is fascinated by the “eerie, surreal beauty of factories, independent of any ecological concerns” so “it’s partly a romantic notion as well as some comment on industrialisation.”

Such dichotomies are his hallmark, humour and a brooding subtext co-existing in a world of strange aliens and cartoon-like characters. There is also a sadness “because the world can be a troubled, violent place for many people“.

“Someone said [my work] was a mixture of innocence and darkness, which I thought was reasonably apt.”

His work can be undercut or underscored by pointed titles: “A lot of artists say ‘Picture 1’, or ‘Landscape 1’. I find that boring and like to have a specific title, sometimes quite long.”

And captions too, such as A space-monster studies the world book of soiled toilet papers (leather-bound edition) on the 2001 drawing Humans are idiots.

He unashamedly enjoys puns: the words “I AM“ in Meccano across a landscape he knew in childhood. The title: “McCahonno set: early morning, Whangaparaoa Peninsula 2006“.

The cultural importance of Mombassa’s

art -- as well as his Mentals output (he quit in mid 2000, around the

same time as Mambo changed hands) and albums with his artist brother

Peter as Dog Trumpet -- lead Sydney Morning Herald critic John

McDonald to note “[his] works coax us to find beauty in simple

things or to think a little more critically about the way we live”.

The cultural importance of Mombassa’s

art -- as well as his Mentals output (he quit in mid 2000, around the

same time as Mambo changed hands) and albums with his artist brother

Peter as Dog Trumpet -- lead Sydney Morning Herald critic John

McDonald to note “[his] works coax us to find beauty in simple

things or to think a little more critically about the way we live”.

The success of the Mentals then Mambo (despite widespread belief, he was never an owner of the multi-million dollar company) allowed him financial and creative freedom: “I could do what I like. A lot of what I do is approachable for normal people. I do some stuff which is a bit ugly and unpleasant and that tends to not sell, whereas the prettier things do.

“But I enjoy doing pretty landscapes, and the ridiculous and unpleasant -- and don’t feel compelled to do either.

“But apart from being associated with iconic institutions like the Mentals and Mambo, I haven’t had a particularly eventful life.”

Most days Mombassa is in his studio at the top of the house, drawing with his charcoal and coloured pencils, sweating in the summer heat and maybe listening to talkback. Or alone with the silence.

A solitary, shy and self-effacing family man, Mombassa rarely goes to concerts or the theatre, has no hobbies and does no exercise: “I consider putting my trousers on a form of extreme sport.”

Although prone to bouts of “gloom” he dismisses analysis: most people experience mental illness, his dad (revealed as a bigamist in the biography) was a solitary kind; and “probably it’s the artists’ temperament sitting by themselves in a room“.

He wasn’t keen on doing the book (“because you have to tell secrets and embarrassing things“) but was talked into it “and it’s an insight into where it’s coming from.”But where it is going? He is quoted saying his art “comes from everywhere and goes nowhere“.

“That might be an off-the-cuff statement,” he laughs. “It does come from everywhere and by ‘goes nowhere’ it just goes onto the page in my room, which is nowhere.

“But I do say ridiculous things sometimes and they don’t always make sense — and sometimes they do in a roundabout way.

“But that one? It’s hard to think up an intelligent reason for saying it.”

post a comment