Graham Reid | | 5 min read

While there is no denying the iconic status of the Sydney Opera House which was formally opened 40 years and is now a UNESCO World Heritage site, it would be much harder to make the case that its designer Jorn Utzon from Denmark made much of an impact on the Sydney skyline.

Certainly not as much as his friend Harry Seidler who was a great supporter of Utzon whose fraught tenure on the project ended with his resignation in 1966. Utzon -- who died in 2008 -- wasn't invited to the opening and never saw the completed building.

The story of Sydney -- and Australian -- architecture is littered with stories of grand and sometimes failed enterprises, but it is also the story of Vienna-born Seidler who was hurried out of Austria when the Nazis arrived and began their systematic persecution of Jews like the upper-middleclass Seidler family who, in the course of two generations, had worked their way up from a penniless immigrant arriving in the city to owning a large and successful garments business.

As the child of this family, Harry would -- as a teenager in Britain in the late Thirties -- be amused and horrified that people cleaned their own dishes. They didn't even have maids, he remarked in his diary.

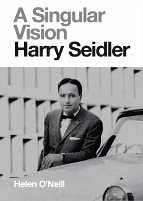

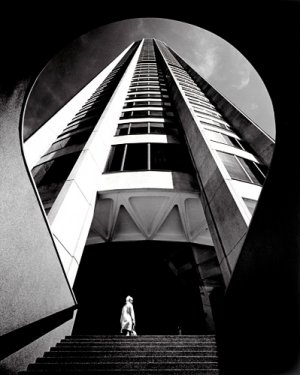

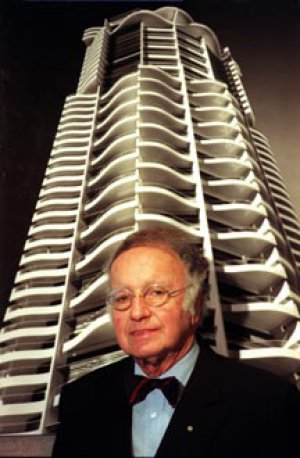

The remarkable story of Harry Seidler -- whose buildings are dotted all around Sydney and include the famous Australia Square (right) and slightly notorious Horizon Apartment tower in Darlinghurst (below, with Seidler) -- is told with readable clarity in this biography by Helen O'Neill who has previously writen about wallpaper designer Florence Broadhurst and a history of the David Jones department stores.

The remarkable story of Harry Seidler -- whose buildings are dotted all around Sydney and include the famous Australia Square (right) and slightly notorious Horizon Apartment tower in Darlinghurst (below, with Seidler) -- is told with readable clarity in this biography by Helen O'Neill who has previously writen about wallpaper designer Florence Broadhurst and a history of the David Jones department stores.

Although clearly gifted -- when he arrived in Britain at 16 he couldn't speak a word of English, the following year he topped Cambridge Technical School in that subject -- Seidler came to architecture by chance.

He was steering himself towards engineering at CTS but the class was full and when he a building course was suggested he thought it sounded alright.

No more enthusiasm than that, but it quickly taught him many of the rudimentary skills he would need and he won a school prize. It was a copy of Architectural Building Construction.

For Christmas that year he was given an architectural ruler and a drawing board. And when he started to seriously consider the buildings around Cambridge he fell in love with Thurso House, a Modernist building designed by the New Zealand-born architect George Checkley.

For Christmas that year he was given an architectural ruler and a drawing board. And when he started to seriously consider the buildings around Cambridge he fell in love with Thurso House, a Modernist building designed by the New Zealand-born architect George Checkley.

As a young man who had travelled to Britain on a German passpaort, he was interned when war broke out (first near Liverpool then on the Isle of Man) and developed a lifelong hatred of any politician who would advocate internment for young political refugees.

Then worse happened, he was shipped of to an even more brutlaising camp in Canada where it was bitterly cold and inmates were treated as badly by the Allies as prisoners in many German camps.

Again, as his scrupulously kept diaries record, he never forgave the British for doing this although -- in one of the many ironies of his life -- it was here he fully engaged his passion for architecture and took classes, did drawings and designs, and set his heart on being a Modernist.

He was undeniably gifted, and he was just 18.

After 17 months internment in these various camps and work on release, he was granted permission to study and headed immediately for Walter Gropius' post-Bauhaus cabal at Harvard where he was accepted as a student.

"The deep rooted revolutionary zeal became part of us. There was something in wanting to make a better world after the war, more than being a revolutionary," he wrote.

"Gropius was just the man to intensify that almost religious feeling in young people, He made us feel, and he actually said it, that we were destined to change the physical world."

That single-minded passion saw him study at Black Mountan College with Joseph Albers and offer his services to Marcel Breuer in New York (he was Breuer's first assistant and did almost all the drawings for houses that Breuer built in the two years after 1946).

That single-minded passion saw him study at Black Mountan College with Joseph Albers and offer his services to Marcel Breuer in New York (he was Breuer's first assistant and did almost all the drawings for houses that Breuer built in the two years after 1946).

Only the fact his family had emigrated to Australia took Seidler to Sydney, a place he thought "What have I come to?" when he arrived, for the sole purpose to design and build his parents a Modernist home.

That had been how they tempted him away from working either in the United States or Britain. He expected to only stay a few months.

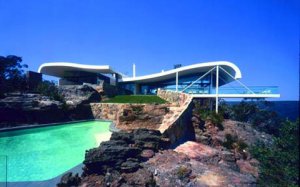

The home he built --the Rose Seidler House -- immediately attracted daytrippers and gawkers, the attention of Australian and international architects, and it won him the Sir John Sulman Medal given by the Royal Australian Institute of Architects.

There are suggestions it was less appealing to live in (too cold in winter, too hot in summer) than it was to look at and photograph.

In a remarkably short time, Harry Seidler - single-mindd, knowing little of the world beyond architecture according to his forcefully supportive wife Penelope, very much a ladies man before marriage and furious in his pursuit of Modernism -- had arrived.

Commissions followed (many from ex-pat Jews and Europeans) and his designs frequently ran foul of local council planning restrictions. This infuriated him and he would take to the popular press to demand artistic freedom for architects and to berate the petty bureacrats who would prevent him from realising his vision.

He wasn't popular, but he didn't care. He just wanted to make great art as architecture.

His design for the Sydney Opera House was short-listed -- a somewhat joyless but efficiently geometric, white-columned glass-walled edifice -- but when Utzon's design (pulled from the "rejected"pile by Eero Saarinen) was chosen he was delighted and wrote a pithy but typical letter to the Sydney Morning Herald.

"Architecture is a language and architects speak it. Most of them just barely manage to speak -- very few ever speak eloquent prose, but it happens rarely indeed that any of them create poetry with just a few words.

"Architecture is a language and architects speak it. Most of them just barely manage to speak -- very few ever speak eloquent prose, but it happens rarely indeed that any of them create poetry with just a few words.

"Our proposed opera house is just such poetry, spoken with exquisite economy of words. But then how many of us appreciate or even understand poetry when we have only ever heard crude language."

At the time Seidler was just 34 and would have almost five more decades of creating poetry in solid form.

This crisp biography -- beautifully illustrated with photographs by Seidler's longtime colleague Max Dupain, Harry's brother Marcell and others -- is the story of the battle for Modernism by a single-minded, often irascible, impeccably dressed, sometimes humourless and unwavering man who made as many enemies as friends.

But a man who -- international commissions aside -- mostly notably left his mark on the architecture of Sydney.

Harry Seidler; A Singular Vision by Helen O'Neill. Harper Collins, $59.99

post a comment