Graham Reid | | 4 min read

The question is very simple and so should the answer be, but let's ask it anyway.

When World War I ended with the armistice on November 11, 1918 what happened to the thousands of New Zealand soldiers – around 40,000 stationed in Europe and Britain – who had left their homeland to fight and were now still in Europe?

The answer of course is obvious: They came back home.

Well no, actually.

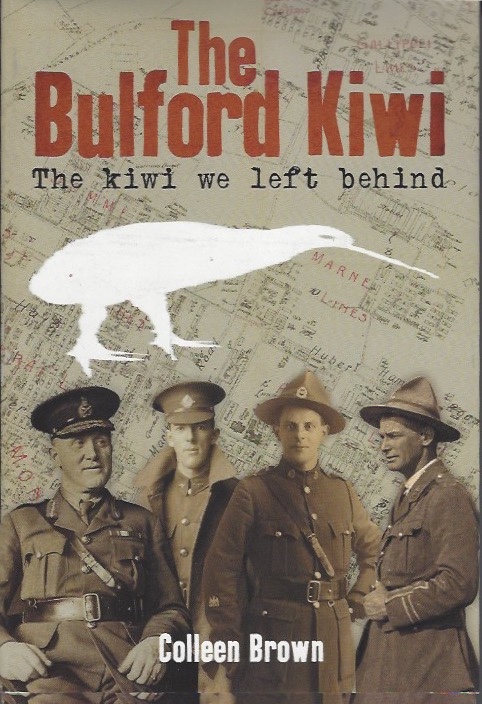

And therein lies the story of this well-researched and thoroughly readable book by Auckland writer Colleen Brown.

Nominally it is about the huge kiwi carved into a chalk hill on Salisbury Plain which New Zealand soldiers dug out. But in fact the story embraces more than that, and much that is cruel, shameful, punishing and an embarrassment to both the British and New Zealand governments of the day.

To backtrack a little – as Brown does because that large white kiwi only enters the story about halfway through this pointed and well-illustrated account punctuated by soldiers' diary entries and letters home. Many New Zealand soldiers had been housed at Sling Camp on the bleak Salisbury Plain when they arrived in Britain before embarking for the war in Europe.

And it was to there that many – a

regular compliment of around 6000, replaced by others when some left

for home – returned.

And it was to there that many – a

regular compliment of around 6000, replaced by others when some left

for home – returned.

But not immediately.

Brown recounts an appalling 240 km march into Germany of selected New Zealand soldiers in an occupying force through rain and mud, the troops' boots worn through, a woeful lack of provisions, sleeping rough and plagued by rats at night . . .

One soldier recounts the day he had his first bath in eight weeks, but was obliged to put on a change of clothes which were in the same parlous state as those who took off.

Yes, they were greeted with flowers and cheers in most places but that takes nothing away from this arduous march which an officer in official records describes as “interesting and enjoyable” but foot soldiers saw very differently.

However by early January 1919 they were on their way back to Sling Camp – in a British winter of snow and sleet, remember – and repatriation.

Or so they thought.

Given the sheer numbers of men and the state of health of many, getting them back home was a massive task of logistics and it ran headlong into a very different world in Britain.

As Brown recounts, before the war there

had been strikes and demands for higher wages from many British

unions which were suspended during the conflict. When the war ended

those activities flared up again.

As Brown recounts, before the war there

had been strikes and demands for higher wages from many British

unions which were suspended during the conflict. When the war ended

those activities flared up again.

Britain was being flooded by returning soldiers looking for work, unions targeted government owned railways, mines and docks.

And the ships in which the New Zealand (and Australian) soldiers were to be taken home in simply stopped sailing.

It was an impasse and on wintry Salisbury Plain in Sling Camp the soldiers – now thinking of themselves as civilians who just wanted to get back to loved ones and the homes and farms they had left behind, sometimes many years before – were faced with the possibility that it could take many months before they could leave.

“To keep the men occupied until they were repatriated” writes Brown, “they had four hours a day, six days a week of compulsory education classes to help reintegrate them back into civilian life and the workforce.”

Many of these men were injured or emotionally damaged, some only then learned of the deaths of battle companions or people back home, some were back at the hated place they had been posted to on arrival in Britain so already had bad memories of its isolation and cruel climate, there was no leave, regular marches . . .

And then the panic when a new flu epidemic hit.

The repatriation system seemed to favour some over others.

“Rumours flourished, were embellished and recirculated. Reports of disturbances and demands by other Dominion soldiers in nearby camps took hold. The process of drafting men back to New Zealand did not appear to be fair. Frustrations surfaced, and discipline became frayed. Fragmented communication lines were unhelpful and the late cancellation of boats bound for New Zealand undermined official broadcasts about the anticipated shipping schedule . . .

“And on 14 and 15 March 1919 the soldiers at Sling Camp rioted.”

In its wake, eight unnamed men – all from the South Island – were charged in court martial proceedings, some having earned gallantry and bravery awards on the battlefields of Europe.

All of this is as much Brown's story as the kiwi carved into the hill in the aftermath of the riots as something to occupy the men.

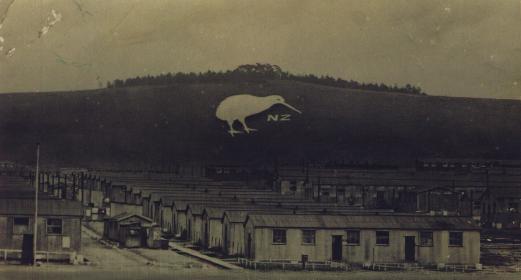

Brown writes of how the 130m high kiwi

was designed to take into account the perspective when viewed from

the parade ground below and the effort required to dig down and clear

the surface earth to reveal the shape which was then filled with

chalk.

Brown writes of how the 130m high kiwi

was designed to take into account the perspective when viewed from

the parade ground below and the effort required to dig down and clear

the surface earth to reveal the shape which was then filled with

chalk.

Of itself it is a remarkable story and left a visible legacy of the men who endured their time in that place.

But even here the story takes a dark turn.

When the men left, who would ensure the

kiwi remained?

And therein lies yet more twists and turns of

finance – the New Zealand government post-war unwilling to continue

to pay a modest sum for its upkeep, Kiwi Polish (an Australian

company) undertaking the role, more government truculence and an

insult paid to Kiwi Polish who then withdrew, the local scout troop

taking over . . .

And eventually the kiwi on Beacon Hill was barely visible. Then gone.

Author Brown – through assiduous

research of military and business records, conversations, and access

to diaries and letters of soldiers and their families – weaves a

remarkable and highly readable tale about a small but significant

period in our history, and how this monument to the fallen by those

lucky enough to survive that awful war has today become a designated

protected heritage site by the British government.

Author Brown – through assiduous

research of military and business records, conversations, and access

to diaries and letters of soldiers and their families – weaves a

remarkable and highly readable tale about a small but significant

period in our history, and how this monument to the fallen by those

lucky enough to survive that awful war has today become a designated

protected heritage site by the British government.

As it bloody well should.

It is there lest we forget, and Colleen Brown deserves great credit for not allowing us to forget those who served and then languished for months – the last not leaving the camp until 10 days short of a year since the armistice – on barren Salisbury Plain, thousands of miles from the green fields and dark forests of home, and their family and friends.

THE BULFORD KIWI; THE KIWI WE LEFT BEHIND by COLLEEN BROWN. Bateman Publishing, $39.99

Anne Martin - Apr 19, 2018

Very good review of an excellent book. The book is well written, very readable and a good introduction to the Great War and its aftermath for many who know little about it.

SaveJoanna Mawdsley - Apr 20, 2018

Excellent review of an excellent book. Books about the Great War can be difficult to read and navigate however this book is very readable and features an area not previously covered. Lots of reference material for further reading.

Savepost a comment