Graham Reid | | 9 min read

James McMurtry: I'm Not From Here

The literary landscape of the American south sets it apart from that of the rest of the country. The hard indifference of William Faulkner’s world is reflected in his lean poetic writing; the inhospitable, suspicious small towns and brooding menace stand stark in Eudora Welty’s stories, and crippling heat brings sweat and malice from every pore in Tennessee Williams’ characters.

The South is a place -- in literature

at least – where cruelty is endemic, the sky flat and oppressive

and snake-eyed characters barely suppress an urge to violence.

Bullet holes in the mailbox. And a

strange car the driveway.

As English author/critic Jonathan Raban

wrote when reviewing a collection of Eudora Welty stories; “The

South is rich only in the goods that money can’t buy. Its natural

landscape is tropically abundant with singularly uneconomic

commodities like magnolia [but] the South has made itself immodestly

rich in language."

That richness is there in Southern

songwriters as well. Lucinda Williams (whose father was a poet)

writes crystalline yet melancholy lyrics in the manner of what she

calls "that dark southern slice-of-life stuff” of the

literature. The Texas songwriting tradition which embraces Butch

Hancock, Guy Clark and - most recently - James McMurtry captures

clear photographic images of a world apart in a few careful words.

Bullet holes in the mailbox. And a slow

train on a trestle.

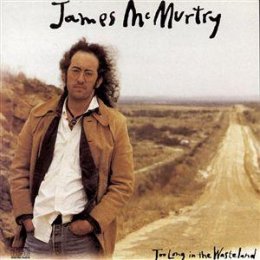

When McMurtry released his debut album

– the polished and nuggety Too Long in the Wasteland – his

Southern connections were apparent.

James McMurtry is the son of novelist

and screen-writer Larry whose screen credits include Peter

Bogdanovich's ’72 adaptation of his shadowy The Last Picture Show

and the Western series Lonesome Dove.

And even though the McMurtrys script

similar small-town scenarios where passions can erupt unexpectedly,

the younger man’s work stands on his own.

When he speaks about Too Long in the

Wasteland which has him on the cover standing disconsolate against a

barren endless flatland he connects immediately to the literary and

family heritage.

“That place isn’t really called the

Wasteland,” he says in a quiet vowel-dragging voice and correcting

a widely held misconception about the album’s title track.

“I call it that, but nobody else

does. The actual name of that place, the small hill I‘m standing on, is Idiot Ridge. It’s in the middle of nowhere and I thought of

that name while sitting on my porch one day. I looked at the bullet

holes in the mailbox and the moon, and got that song right away.

“That house was built by my great

grandfather and my father spent his early years there, but by the

time Larry was seven the pick-up truck had developed to a point where

a rancher could live in town and still farm.

“My parents rented the house and

lived in town for years and my grandfather deeded it to my Uncle

Charlie who got his mall in that box with 'McMurtry' on it which is

on the back.

“Charlie handed the house to Larry

but he never got rural delivery so things just stacked up. Rats and

scorpions nested in there so we never used it. We kept it mostly to

shoot at - it’s a pretty good size and you could hit it with a

pistol.”

He pauses for a long time then adds

with a reflective and a barely audible touch of mysterious colour. “I

put a few of those holes there myself - it always had a couple in it.

Somebody shot at it from the road.”

Glance at the road photographed on the

cover and it is hard to imagine who. The ragged line of clay runs

unevenly across mile after mile of empty land.

And that is McMurtry’s territory. His

lyrics tell of a young boy's anger exploding into pistol fire,

silently driving through “the outskirts of an old familiar town

with the misty darkness coming down” and life on the fringes. The

wasteland.

His compressed lyrics team with stories

just beyond the end of the lines he is singing and which hang

incomplete waiting for a context. They are ghost tales and the

characters all too real for being caught at one moment. “That dark

southern slice-of-life stuff.”

If McMurtry were only a lyricist

however, the album would sit with other worthy but unlistenable

items. But Wasteland leaps to life musically because producer John

Mellencamp called in members of his own band, guitarist Dave Grissom

from Joe Ely’s hard rocking country group, singer Ashley Cleveland

(who usually works with John Hiatt) and bassist David Pomeroy from

Emmylou Harris’ group.

That line-up adds fire-cracker backing

to songs which McMurtry admits were largely incomplete before

recording.

Ironically, one of the finest songs on

the album -- Painting By Numbers which deals with emotional

detachment -- was written quickly in the studio as McMurtry reflected

back on his schooling and included a line from a friend ("just

be all you can be”) who had recently returned from a tour of duty

at the Panama Canal.

The shoulder shrug indifference of the

song ("you’re painting by numbers connecting the dots, you

work from the neck down as often as not") leads him to talk

about his own life -- one of regularly packing a suitcase.

McMurtry was born in Fort Worth, Texas

in 1962. His parents separated when he was young, his father

(previously English professor at the University of Richmond) taking a

teaching job in Richmond, Virginia.

“I moved up there with Larry and grew

up in a place around Leesberg – but at that point Washington DC was

expanding into Virginia and there were a lot more people commuting.

More traffic lights and more people.

“Where once it took maybe an hour to

get to town now it took two. My father had a rare bookshop in DC so

he decided to live in the town. I didn’t care for that so mostly I

went to hoarding schools to get out. I was about 14 and not ready for

the city.”

“I had no idea what I wanted to be -

or thought at that age I should have any idea. I majored in English

at college and went to the University of Tucson mainly because I had

never known anybody who went there. I thought Tucson was the ugliest

place I’d ever seen -- but it's surprising how you get used to it,"

he says dejectedly.

“I never did graduate -- I did about

four years -- but at that point didn't care much about being a

student. I was just painting by numbers, I guess.”

Having been taught guitar by his

mother, he tuned in to literate songwriters like Kris Kristofferson

and slowly. laboriously slowly, started to write himself.

“I remember hearing people say they

used to play guitar but had quit. I couldn't imagine that - it’s so

easy, like breathing, so why quit?

“I was never really drawn to prose

writing although I read good prose every now and then. To write prose

you have to read a lot and have a lot of places to steal from -- or

have observed a lot of different types of writing. I’ve listened

more than I've read.

“I liked the way Kristofferson

stacked up words so neatly - a poetic style. Song and poetry aren't

the same but Kris is a Rhodes scholar and knows about rhythm and

metre – things a lot of people forget these days.

“I took a few poetry classes so I do

think about that stuff, but a song is different and you can't carry

those notions too far. Craft helps but you have to be careful not to

overcraft.”

Much like a rootless character in one

of his father’s westerns, McMurtry shifted from place to place. At

12 he went to Guatemala “with a friend of mine whose grandfather

was a timber baron" and Switzerland, England and Rome are among

his childhood recollections.

He taught at a boarding school in

Madrid for a summer and ticks off San Antonio and Austin in Texas as

places of temporary residence. But always he drifted back to “the

Wasteland” and sat amid his father’s 10,000 books.

His playing career began in earnest in

'84 in Tucson when he joined up with the Arizona Old Time Fiddle

Association but quickly tired of the conservative nature of the music

and musicians who clung doggedly to bluegrass flat-picking and fiddle

traditions.

By the summer of '84 he was in a

restaurant bar in Alaska playing fiddle tunes on guitar for mountain

climbers and skiers “to keep them there drinking beer.”

“They had about 40 different kinds of

imported beer but everybody was into cheap stuff anyway. They were

saving their money for air trips up the glacier so didn’t have much

money. The little they did they certainly weren’t interested in

putting in a jar for some folkie musician.”

McMurtry drifted off again, back to

“the Wasteland”, and finished writing some songs.

Some of his song of alienation -- the

laconic I’m Not From Here (“I just live here") date from

this period. He scribbled fragments of lyrics on scraps of paper and

distilled them into half a dozen songs.

In ’87 he appeared at the New Folk

contest in Kerrville, Texas and was one of six winners. He met with

fellow-songwriter Fred Koller, completed more songs and even had one

considered for the soundtrack of Lonesome Dove (a television

mini-series based on his father’s book and in which he has a small

ride-on part).

It didn’t make it, but lead to the

meeting with Mellencamp - and eventually Too Long in the Wasteland.

For the past year McMurtry has been on

the road with his small band and fronting for some diverse and

creditable headliners. They crossed America one way with guitar

rockers The BoDeans, slipped back again with new country star Nanci

Griffith, then teamed up with hard rockers The Del Fuegos before the

tour headed north and got into colder climes. McMurtry and band

begged off and rejoined the BoDeans tour.

Right now James McMurtry is considering

his options -- there are thoughts about a new album although he

doesn’t have enough material written yet, “then again, I didn’t

have enough for the last one and although you can rough things out it

becomes clear in the studio what works and doesn’t.”

And there is more touring.

Meanwhile there is Too Long in the

Wasteland to be enjoyed, its images of small towns and "some

bright future somewhere down the road to points unknown” sung with

world-weary detachment and evoking the same hard, unsentimental

images as writers from that distinctive Southern tradition.

When writing about Eudora Welty, critic

Jonathan Raban said, “behind every voice there is the powerful

presence of an incommunicable life, subtle, tacit, full of

implications and odd imagining. [In her] world there is always much,

much more than meets the eye . . . every detail is handled as a vital

clue and her stories demand to be read almost as painstakingly

carefully as they have been written. They offer no handy

resolutions.”

Raban might well have been writing

about James McMurtry.

post a comment