Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Brown, Alexander, Malone: One for Hamp (2002)

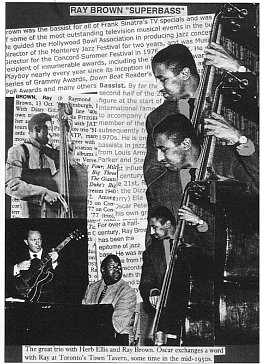

Ray Brown great practical joker. Once,

in Japan, Brown --- bassist in pianist Oscar Peterson’s famous

drummerless group, the most highly paid trio in the jazz world in the

1950s -- went to a pachinko hall, one of those gambling parlours

where you are blinded by blazing neon and deafened by the incessant

roll of small steel balls. He won and, instead of cashing in his

ballbearings, filled his pockets with them.

Before the concert he slipped a few of

the marble-sized silver balls onto the strings of Peterson’s piano.

When Peterson, then the most famous jazz pianist in the world

alongside Dave Brubeck, started to play the sensitive ballad But

Beautiful, “every note sounded like a whorehouse piano"

according to guitarist Herb Ellis.

That was Ray Brown the Joker for you.

But he also played with so many great musicians that he seems almost

promiscuous: Sinatra, Armstrong, Lester Young, Sonny Stitt, Anita

O’Day, Quincy Jones (whom he managed) . . .

Brown was a founding member of Dizzy

Gillespie’s groundbreaking bebop band and later became musical

director and husband to Ella Fitzgerald. He is on over 2000

recordings and someone on whom praise has descended with almost

embarrassing frequency.

In Gene Lees' 1988 The Will to Swing

biography of Peterson, an unnamed bassist says Brown was so far ahead

of everybody musically there was no comparison: “He’s a tall man

in a crowd of medium to small men. That’s how he stands out.”

That’s the stature Brown enjoyed,

right up until his death in July 2002. His passing didn’t go

unnoticed, but let’s be honest. Jazz bassist dies, the world moves

on in the blink of an eye.

Brown was born in Pittsburg in October

1925. He took piano lessons a kid and - unlike classically trained

Peterson with whom his name is most often linked - his dad encouraged

him to listen to and play like jazz musicians such as Fats Waller and

Art Tatum.

Maybe because of those high

expectations, the young Brown gave up the ivories and took up

trombone. Dad couldn't afford to buy his boy a trombone but a bass

was available at school so . . .

He gigged on weekends, got his own

instrument when the school repossessed theirs, and toured with a

local band as far off as Miami.

Then he lit out for New York and –

this is a great story -- the night he arrived went down to 52nd

Street and saw Errol Garner, Art Tatum, Billie Holiday and Coleman

Hawkins. He met pianist Hank Jones who introduced him to Gillespie.

Brown picks up the story.

“Dizzy said, 'Do you want a gig?’ I

almost had a heart attack. Dizzy said, ‘Be at my house for

rehearsal at seven o’clock tomorrow'.

“I went there the next night and got

the fright of my life. The band consisted of Dizzy, Bud Powell, Max

Roach, Charlie Parker and me. Two weeks later we picked up Milt

Jackson who was my roommate for two years.”

Quite an introduction to the jazz life,

during which the musically inquisitive Brown learned bebop inside out

and practiced relentlessly, a habit he took with him when he joined

pianist Peterson in 1950 for an affiliation which lasted 15 years.

Quite an introduction to the jazz life,

during which the musically inquisitive Brown learned bebop inside out

and practiced relentlessly, a habit he took with him when he joined

pianist Peterson in 1950 for an affiliation which lasted 15 years.

When the Peterson Trio travelled, Brown

would hang out with other bassists from the jazz and classical world,

or he and Ellis would rehearse endlessly, anticipating musical

possibilities so they could extend them on the bandstand.

When drummer Ed Thigpen came in as

Ellis' replacement, Brown did the same with him for many years. Then

he quit. ‘Mr Brown Goes to Hollywood’ was the headline in the New

York Post in November 1955.

Critics hailed his years with Peterson

(“the most effective music collaboration of the 50s,” said

Leonard Feather) but for Brown it was time to kick back.

“It wasn’t just the 15 years with

Oscar, it was 20 years on the road counting Dizzy Gillespie and other

bands I was with, and all those tours with Jazz at the Philharmonic.

“So it's time to reconsider.”

But within 48 hours of arriving in

California Brown was working again. And he never stopped. He formed

his own trio, opened a club, played with singer Ernestine Anderson

and, most profitably, teamed up with Jamaican-born, Oscar-influenced

pianist, Monty Alexander, who has most recently come to wider

attention for his reggae-jazz albums with guitarist Ernest Ranglin.

It was with Alexander and guitarist

Russell Malone that Brown made his final recordings.

The album appeared simply under their

own names, the album is an almost unadventurous affair – but on

close inspection unwittingly favours much of Brown’s history. There

are tunes by Fats Waller, Dexter Gordon and John Lewis of the Modern

Jazz Quartet alongside his own tunes, one of which is dedicated to

Lionel Hampton. There's also Fly Me to the Moon.

The album came with a limited edition

bonus CD drawn from the Telarc label's files. Okay, it's a narrow

sliver of a long career but here is Brown alongside those he

influenced and inspired (Christian McBride, a bassist of the Marsalis

Generation) and recorded live. He shines.

Oscar Peterson, the musician who knew

Brown best, mused in 1987 of their 37 year association that Brown’s

gift was difficult to describe: “His talent had a kind of depth...

it's not just intuitive. His talent is almost ethereal."

In those years Brown and Ellis were

with Peterson and practicing every day, rehearsing possibilities and

alternatives, Brown had a saying: “See if you can hear this.”

Maybe that's what Peterson was saying

too. And it’s never too late to see if we can.

post a comment