Graham Reid | | 7 min read

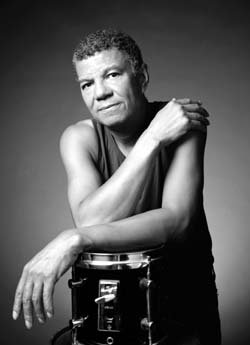

When fame called on Jack DeJohnette

during his period in Miles Davis' innovative electric band of the

late Sixties and early Seventies, he was ready for it.

Acclaim outside their own world is

unusual for jazz musicians, but DeJohnette had tasted it a few years

previous in the Charles Lloyd Quartet which enjoyed that rarity, a

jazz album which was a hit.

Forest Flower, recorded live at

the '66 Monterey Jazz Festival, hooked in proto-hippies as much as

the jazz crowd and the Quartet started playing the rock circuit.

Their Love-In album was recorded in January '67 at San

Francisco's famous Fillmore Auditorium where the Grateful Dead and

Jefferson Airplane played regularly.

“That's right,” laughs 68-year old

drummer DeJohnette. “The Charles Lloyd Quartet preceded Miles at

the Fillmore. It was quite a time: Sly and the Family Stone, bands

like Blood Sweat and Tears, and Chicago. It was very fertile time for

experimentation, the Beatles were big and Ravi Shankar had introduced

Indian music to American audience at festivals. There was a lot of

cross-pollination in music, and jazz too.”

American jazz musicians – through the

agency of Lloyd, Davis and then the alumni of Davis' revolving-door

bands such as keyboard player Herbie Hancock and guitarist John

McLaughlin – bridged the worlds of jazz and rock, and in the

process created a new form. Davis found a younger audience, but at

the expense of longtime fans who felt the trumpeter, then in his 40s,

was now lost to jazz.

They were musically exciting -- and

often demanding – times, and friendships formed on bandstands or in

the studio lasted lifetimes.

Also in Lloyd's quartet was a hot young

pianist, Keith Jarrett, with whom DeJohnette still plays today. With

bassist Gary Peacock, they have been universally acclaimed as the

most consistent and important jazz trio of the past two decades for

their nuanced exploration of standards.

Ironically, given his long career and

the calibre of players he has worked with – from West African kora

player Foday Musa Suso to avant-guitarist Bill Frisell –

DeJohnette's most publicly acknowledged work in the past decade is

far removed from that exploratory period with Lloyd then Davis.

In 2009 he won a Grammy for Best New

Age Album for his meditative Peace Time, a follow-up to his

ambient Music in the Key of Om on

which he also created hour-long landscapes of synthesizer sound.

DeJohnette's career between the

musically expansive Lloyd group and his New Age music – the latter

derided by jazz critics – is peppered with great jazz names he has

played alongside: guitarists John Scofield and John Abercrombie;

keyboard players Hancock, Chick Corea and Bill Evans; saxophonists

Wayne Shorter, Joe Henderson and Lee Konitz . . .

But it was in the studio with Davis and

producer Teo Macero that he was at a cutting edge of a new music.

Davis and a coterie of musicians created such cornerstone albums as

Bitches Brew and A Tribute to Jack Johnson.

But it was in the studio with Davis and

producer Teo Macero that he was at a cutting edge of a new music.

Davis and a coterie of musicians created such cornerstone albums as

Bitches Brew and A Tribute to Jack Johnson.

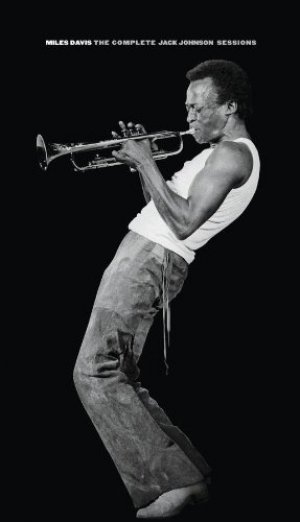

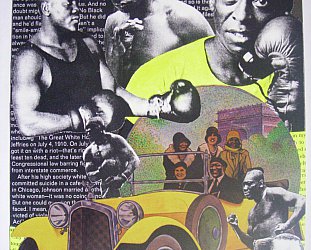

While Bitches Brew has long been accepted as announcing the fusion movement where rock and jazz collided, the Jack Johnson album – conceived as the soundtrack to the documentary film by Bill Cayton about Johnson, the first black world heavyweight boxing champion in 1908 – has often been overlooked.

On release in early '71 it failed to ignite the charts or imaginations as Bitches Brew had done.

In recent years – especially with the 2003 release of a five CD set of the complete Johnson recording sessions – the album has undergone a critical reassessment and is now hailed as the equal of Bitches Brew.

As with the Brew sessions, Davis and his cast – which included guitarist John McLaughlin, Hancock, saxophonist Steve Grossman, funky electric bassist Michael Henderson and many more – improvised at length and Macero later edited together the two side-long pieces for the album which, by chance, didn't credit DeJohnette on the cover. (It named Billy Cobham who was also on some of the sections).

As innovative and challenging as it

was, DeJohnette doesn't see Jack Johnson as revolutionary

because “it was not any more than what rock musicians would do, just

go into the studio and record and keep the tape rolling. Teo would

patch it together and get those fresh moments and Miles would approve

of it.

As innovative and challenging as it

was, DeJohnette doesn't see Jack Johnson as revolutionary

because “it was not any more than what rock musicians would do, just

go into the studio and record and keep the tape rolling. Teo would

patch it together and get those fresh moments and Miles would approve

of it.

"So it was an on-going improvisational process in the studio.

“But sometimes Miles gave clear instructions and he directed everything so it was a work in progress being documented. I'm on it, but some of [the Johnson album] came from the Bitches Brew sessions.”

For the past few years DeJohnette has been presenting a multi-dimensional tribute to Davis and Johnson with his Soundtrack to a Legend concert . The performance mixes live music from his young band with some Davis material and has Cayton's film screening behind them.

“Every time we do it we make changes. There are monitors on stage so we can work with the time code. It's quite unique. We bring in or out the audio and music, and we can take in dialogue from the film too.

“Each time we make permutations on it and change it around. It's celebrates Miles' music and also the life of Jack Johnson . . . and especially the racial commentary in the United States and what it was like for him being the heavyweight champion of the world and being black after all the white champions.”

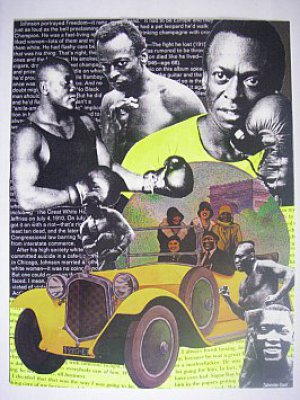

Johnson's is a remarkable story full of heroism, pathos, tragedy, the excitement of the ring, and his taste for fast cars and white women. Eloquent and well spoken, his most famous quote was “I'm black, they never let me forget it. I'm black alright, I never let them forget it.”

He lived fast, smoked cigars and drank champagne (“going out with white women and putting that in the establishment's face,” says DeJohnette) and after his victories there were often lynchings.

One “Great White Hope” after another – a phrase coined by Jack London --- fell to his fists but after he was prosecuted under the Mann Act (for taking a woman across state lines for an immoral purpose, the same that would get Chuck Berry later) he fled the country and became an itinerant showman.

And he was defeated by Jess Willard in Havana . . . but many said he took a dive.

“He was a very intelligent guy and played double bass,” say DeJohnette. “So he was an enigma to the establishment and he made quite a bit of money, they were trying to stop him with the Mann Act. He came back eventually but that was controversial because in that fight with Jess they say he lay down.

“You can see the picture of him on the canvas – and they had been fighting like 27 rounds in Cuba in a temperature of 115 degrees – and he's got both arms over his eyes. He said he threw the fight because he made a deal with the authorities so he could come back because his mother was very ill.”

Johnson was killed in car crash in 1946. He was 68.

Johnson's life was inspirational for Miles Davis who also took fight lessons and was mentored by Sugar Ray Robinson. But it was Johnson's abrasive nature and confronting of racism head-on which also appealed, especially in the late Sixties with the rise of the Black Panther movement and black pride.

It was in that political and social milieu – along with the burgeoning rock scene as exemplified by Jimi Hendrix and Sly Stone – which Davis conceived the swirling, often aggressive and edgy music to Cayton's documentary.

DeJohnette's programme addresses and incorporates all of these elements, he says: “On a musical level it's inventive and we come with no prior expectations, and we work with that. On an educational and cultural level it is important because people can then understand race relations at that time. Then want to go and find more, so it will enlarge their curiosity about this man and this music.”

Ironically given his long career and the calibre of players he has worked with – from West African kora player Foday Musu Suso to avant-guitarist Bill Frisell – DeJohnette's most acknowledged work has come in the past decade and is a world removed from Jack Johnson.

In 2009 he won a Grammy for Best New Age Album for his meditative Peace Time, a follow-up to his ambient Music in the Key of Om on which he also created hour-long landscapes of synthesizer sound.

“These are projects I like to do, Music in the Key of Om was made for healing. My wife is a vibrational healer and counsellor and I made it for her and people started to like. My younger daughter is a masseuse and a practicing acupuncturist and working with traditional Chinese medicine and she's started using it.

“Particularly now our world is in such chaos with politics and wars, there is so much stress at this point. People need to recharge their batteries.”

He then embarks on a lengthy digression about the consequnce of violence and guns in America, and how constant barrage of breaking news allows us no respite from the woes of the world while desensitising us to violence.

“The consequence of our culture is that we don't have time to step back, because then the next thing happens. With the right conviction music can be part of an instrument to bring about healing but we have to stop and look and see what is going on. You don't need to have news on television 24/7.”

DeJohnette says he doesn't feel he ever did anything to invite a new audience in to his music: "Not really, I continued doing what I did and found an audience because I believed in what I was doing and I'm still doing that today. The new group I have are in the process of making some downloads of performances and CDs . . . and it's all my music."

He laughs about his long and constantly creative life -- "I'm still a work in progress" -- but notes the final word on Jack Johnsn however came from a politician, not a musician.

“John McCain actually gave Jack Johnson a pardon last year.

"Isn't that something?”

post a comment