Graham Reid | | 10 min read

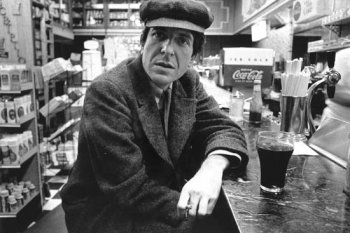

Leonard Cohen: In My Secret Life (from Ten New Songs)

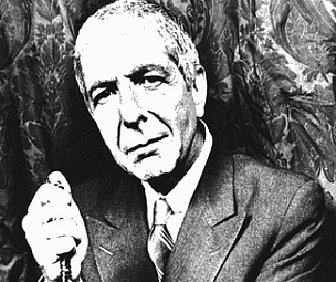

Even the writer Pico Iyer, who knows him better than most, concedes Leonard Cohen – so melancholy he used to be referred to as “a one man Joy Division” – presents a problem.

"He is for most of us,” Iyer wrote in Sun After Dark, “a figure of the dark, sitting alone sometime after midnight and exploring the harsh truths of suffering and loneliness . . . His songs and poetry have always been about letting go and giving things up, the voluntary poverty of a refugee from comfort”.

So who is this man whose songs have

been covered by artists as diverse as Willie Nelson, Straitjacket

Fits, Aaron Neville, the Pixies, John Cale, REM and Billy Joel? This

Jewish-Buddhist and former ladies' man whose Hallelujah the

late Jeff Buckley and others fashioned as a secular prayer?

Cohen – now 76, packs stadiums with

thoughtful songs about hearts and souls – but he also wrote Don't

Go Home With Your Hard-On (with poet Allen Ginsberg and Bob Dylan

on bawdy backing vocals) and of getting a blow-job in the Chelsea

Hotel.

He recorded Death of a Ladies' Man

in '77 with Phil Spector, inspired a song cycle by the classical

composer Philip Glass and is the subject of many biographies. He's a

public performer with a very private life.

Cohen has long been considered

enigmatic, a perception enhanced when he went into the Mt Baldy

Buddhist retreat in California for five years until '99.

But he was always different, and out of step with history when he released his debut album in '67. This was the psychedelic world of Hendrix, Cream's Disraeli Gears and Sgt Peppers, the air heady with marijuana and anti-war activity.

Songs of Leonard

Cohen delivered intense,

monochromatic ballads sung over acoustic guitar.

Songs of Leonard

Cohen delivered intense,

monochromatic ballads sung over acoustic guitar.

But he wasn't a folk singer. As Cohen

biographer Stephen Scobie observes, Cohen was never interested in the

main threads of 60s folk; unearthing old ballads or political

protest: “Take these two things away and basically all that's left

is the notion of the guy with the acoustic guitar . . . the idea of

the singer-songwriter working in a fairly simple musical medium was

the aspect of folk Cohen was able to exploit.”

British rock writer Nigel Williamson

also notes “his influences were unusual, if not unique, in

rock'n'roll at that time.”

They weren't – for the most part –

from music at all. And aren't today.

Cohen – 33 when Songs was

released – was an established writer in Canada with four poetry

collections and two novels behind him. Jim Morrison may have styled

himself a poet – but here was the real thing.

Born in Montreal, Cohen – of an

English-speaking Jewish family in a predominantly Catholic,

French-speaking city – came to poetry in his teens and as another

biographer Ira Nadel says, “that was a voice that spoke to him.”

He hung out with local poets (notably the self-promoting Irving Layton) and was profoundly affected by the Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca. Cohen would later set one of Lorca's poems to music (as Take This Waltz, '88) and name his daughter Lorca.

And just as Lorca explored themes of identity, sexuality and death, so too would Cohen. Repeatedly.

Lorca was also fascinated by music –

notably gypsy song, another later influence on Cohen – and at

Jewish summer camp around this same time Cohen picked up guitar.

It wasn't either/or between music and

poetry, says Nadel. “He's beginning to write poetry as he's

beginning to make some gestures towards being a singer”.![]()

And when he discovered the Beat

movement – Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg and

others – it was Jewish-Buddhist Ginsberg, the most musical of them

all, Cohen gravitated to.

Ginsberg wasn't a poetic influence but

showed being a writer was possible, and a poet needn't be bound by

conventional behaviour. Openly gay, bohemian and funny, Ginsberg

wasn't like the buttoned-down types Cohen encountered in academic

Montreal.

Scobie: “Ginsberg demonstrated to

Cohen some of the ways in which one could make a very public career

of being a poet.” As had Layton.

Ginsberg also became a friend and

confidant to another great influence on Cohen, Bob Dylan, who – in

increasingly literary lyrics – showed poetry could be taken to a

wider audience through song.

Williamson:

“By '65 you've got Dylan singing about [poets] Ezra Pound and TS

Eliot in Desolation Row.

That

must have been hugely encouraging to Cohen who had this intellectual

depth and literary sensibility which he might have imagined couldn't

be satisfied in popular music. Suddenly Dylan proved it could.”

And Cohen was ambitious, as Rolling

Stones' Anthony DeCurtis observes: “Having done the work, I

think he wanted to find the ways of getting [it] to a larger number

of people. As happy as he was with the literary success he enjoyed in

Canada, I don't think that was enough for him.”

So amidst the psychedelic guitar noise

of '67, Cohen's was the quiet voice people paused for . . . and

they've never stopped listening.

Cohen has released more than a dozen

albums and his return to performance in '08 after a 15-year absence

was greeted with an outpouring of devotion – and necessary income.

Cohen had lost most of his money in '05 (around US$5 million) to a

former manager.

But Cohen' music today is very

different from that spare folk of his earlier years.

Professor

Paul Morris, head of Victoria University's school of religious

studies, recalls seeing Cohen at the Royal Albert Hall, London

in '70, one man and a guitar – and the song Avalanche, a

Nick Cave favourite, stood out: “I'd never come

across a song so desperate and

unhappy, it tore into me, an incredible ragged and raw sound. Then I

saw him last year with his nine piece band and it is amazingly

smooth.”

Cohen's reframing of his songs is largely down to his band, among them backing singers and multi-instrumentalists the Webb Sisters (Charley and Hattie) who -- although English and from what Charley calls “a choral-folk background” – also have a trans-Atlantic sensibility after working in Nashville.

The

Webbs and singer Sharon Robinson -- co-credited on Cohen's Ten

New Songs album of '01

which marked his return after Mt Baldy – say Cohen generously

listened to the band's suggestions for new arrangements.

Hattie Webb:

“Leonard was open to everyone bringing their own musicality, but we

were aware of honouring the songs. Rehearsals were a process of

working together and everyone finding the song within themselves.”

Add in Robinson's

diverse background – r'n'b soul to Vegas gigs with Ann-Margaret –

as well as Spanish guitarist Javier Mas, keyboard player Neil Larsen

and saxophonist Dino Soldo (from jazz backgrounds), Cohen's longtime

bassist/musical director Roscoe Beck, session guitarist Bob Metzger

and percussionist Rafael Gayol and you have an ensemble of rare

depth.

In Cohen's music

today there are suggestions of Jewish and gypsy music, Americana,

holy folk and more.

Charley Webb: “You

can also hear some of the Greek influences from when he lived on

Hydra [in the 60s] and how chord changes and melodies were influenced

by that time. You can hear his artistic travels in the songs.”

Morris: “The

[old] songs are instantly recognisable but have a whole new melodic

framework. Although he decries the Spector album, what he's done is a

very sophisticated version of that surround-sound . . . although it

has gone down a couple of octaves and been rounded off.

“He's

like a 20-year old bottle of cabernet sauvignon.”

Robinson – who first wrote with Cohen

in '80 and acknowledges Ten New Songs “was

more a poet's record, because he hadn't been singing a lot before it”

– says Cohen's oblique lyrics allow her to explore musical ideas,

such as the use of Spanish guitars at the start of Waiting

for a Miracle, that the

work of other more literal writers don't.

And Cohen has

always been sympathetic to women and the feminine.

“Like

Leonard, I've tried to figure out the terms and basis of our

existence and the masculine/feminine is an inherent part of that.

That's something we both understand and work to incorporate.”

Cohen's music can also be an evolving revelation for the musicians says Charley Webb: “On certain nights some of us can be highly moved by a particular song which before has resonated in a different way. It'll be more profound.”

Perhaps because his lyrics reference Christianity and Buddhism, and that consistent thread of Jewishness.

Morris: “He is

Jewish not only by name – 'Cohen' easily identifies you -- but when

he became a Buddhist he said he didn't have a new religion because he

never gave up the old one.”

Morris

notes a large number of Jews of Cohen's generation were drawn to

Buddhism – particularly austere Zen -- as an antidote to the worst

aspects of modernity. But texts and practices of Judaism – from

'69's Story of Isaac

(a Vietnam-era metaphor of one generation sacrificing the next) to

Who By Fire

and If It Be Your Will

later which refer to scripture – always informed Cohen's lyrics,

even after his embrace of Buddhism.

“Jews

come from a highly intellectual, textual tradition and are drawn to

the most austere forms of Buddhism, in Cohen's case Rinzai Zen,

sitting practice, and it's an amazing strain – but he claims it has

kept him sane.”

In an insane world

where your fortune disappears overnight, maybe sitting in silence is

a valid response?

Morris

notes Cohen – of priestly lineage – last year offered the

blessing from the Book of

Numbers to

an audience in Israel:

“May God lift his face

to you and grant you peace, may God bless you and guard you, may God

cause his face to shine on you and be gracious to you.”

“He

also made the priestly sign – which was rather perverted by Leonard

Nimoy in Star Trek,”

laughs Morris. “It is almost identical, that V sign, and Cohen made

that.”

Such personal

gestures, as much as the diverse and often deeply mystical content of

his songs, add resonance to Cohen's life and work. He reaches people

in different, subtle ways.

“But

you kind of think he always just told the truth.” says Morris. “And

given the history of his songs he honed that truth into art. Part of

his power is his sheer conviction in saying, 'This is my truth, take

it or leave it.'”

Charley Webb says

certain songs have different effects on audiences, nowhere more so

than during that concert in Israel where Cohen guided the political

conversation before and during the performance (to 50,000 in a

football stadium) to the cause of the concert, the apolitical

Bereaved Families for Peace organisation.

“The

backgrounds of the countries we visit have an effect on which songs

touch people. In Poland or France The

Partisan has a rumbling

which becomes a roar of feeling from the crowd, not just vocally but

emotionally.

“In

Helsinki the crowd was reserved and pensive, slowly taking the

concert in. By the end you could hear a pin drop when something was

being said by Leonard. Compare that with Sligo in Ireland where the

presence for them is his music. People were singing along and dancing

in the aisles.”

Hard to believe

the former “one-man Joy Division” who now skips on stage, a

“refugee from comfort” in an expensive suit, could have people

dancing in the aisles.

But Cohen has

constantly reinvented and re-explored himself and his music. He, and

it, are in for the long haul.

At Mt Baldy, Cohen

said to Pico Iyer, “To me, the kind of thing I like is that you

write a song and it slips into the world, and they forget who wrote

it.

“And

it moves and changes, and you hear it again three hundred years

later, some women washing their clothes in the stream, and one of

them is humming this tune.”

If

that happens with a Cohen song – and it probably will – it'll

more likely be Hallelujah

than Don't Go Home With

Your Hard-On.

post a comment