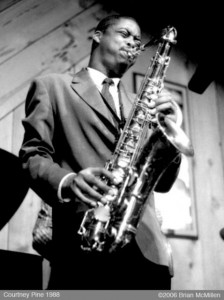

Graham Reid | | 7 min read

Courtney Pine is diverted from telling

his daughter how Tony Blair trounced the opposition and of the legacy

of John Major.

“She's four months old, it’s never

too early to start,” he laughs, then embarks on a discussion about

cricket.

“You’ve got a good team – and

it’s a rebuilding time,” he offers charitably.

Politics, family and sport? These are

unexpected matters from a jazz musician, but then, Courtney Pine is

no ordinary jazz musician.

A business-conscious saxophonist who

emerged a decade ago with technical ability to burn, Pine is part of

the new generation riding the wake of American trumpeter Wynton

Marsalis, whose insistence on a back-to-the future approach, paying

homage to earlier masters, reset the compass of jazz in the early

Eighties.

Suddenly sharp suits and early Miles

Davis cool were the vogue; Ellington and Coltrane the names to drop;

free jazz of the Sixties and Seventies consigned to the rubbish bin

and albums made to sound like 1958, not the tenor of the times.

Perhaps the times were too confusing:

hip-hop kids were sampling jazz licks, instruments came with digits

instead of a name and “acid jazz” implied a chemical infusion as

a substitute for native talent. Difficult times . . . so backwards

was the way forward.

Then there was Pine, London-born of

Jamaican parents and as comfortable talking about reggae poet Linton

Kwesi Johnson as Charlie Parker, as photogenic as he was

misrepresented as the first black British jazz musician.

While young Americans genuflected before the altar of Marsalis’ neo-conservative movement, Pine was planning albums which assimilated reggae. And within the British context he was timely - the film Absolute Beginners put jazz back into the foreground, rock magazines were lining up for the Next Big Thing (jazz, briefly, as it happened), there were photo shoots for fashionable monthlies . . .

Pine was a made man. And he’d signed

to Verve, the American label distributed by powerful international

label Island, then repositioning itself as the market leader by

signing young Americans and seducing back old school names such as

Herbie Hancock and Joe Henderson.

Suddenly Pine was part of the bigger

picture, he played the Montreux Jazz Festival, toured with the George

Russell Orchestra, founded the World’s First Saxophone Posse and

Jazz Warriors, sat in with Art Blakey . . .

Courtney Pine, good copy and a pure

product of his times – if perhaps a victim of too much expectation

from someone still only 22 at the time of his impressive debut

Journey to the Urge Within..

“The first few albums I was learning

in public,” he admits. “I wasn’t going out there to say l knew

everything about jazz. I'm not American, we don’t have that in our

backdrop.

“I did a reggae album because a lot

of people were saying, ‘lIf you‘re influenced by reggae, where is

it‘?’ They couldn’t hear it even though I was using bass lines

directly from reggae. So I felt l’d get that question out of the

way and could continue on this path.”

That path -- a decade on, seven albums

behind him -- has now led him to hip-hop and the turntable-scratching

that kids half his age claim as their own music.

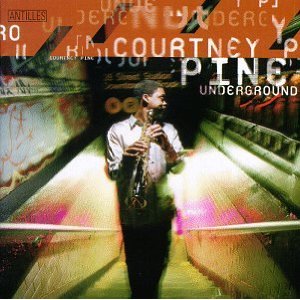

Pine's new album Underground finds him

with a band of smart young American peers (Marsalis alumni bassist

Reginald Veal and drummer Jeff Watts included) and DJ Pogo on

turntables.

But the album is also inspired by

Cannonball Adderely, Lee Morgan and others, all names familiar

in the jazz canon. Even so, some listeners are struggling - and Pine

has some sympathy with their difficulties.

“When the jazz buff looks at a

saxophone player they can say, ‘That rendition of Body and Soul

wasn’t as good as Coleman Hawkins’, and, ‘He’s not as good as

Ben Webster’. But when they see turntables, what can they compare

it to? It’s a whole new learning curve. Technology's led us to

where the spirit of jazz has disappeared and Wynton has a point --

‘how can you let an electronic sound dominate what you are doing?'

You shouldn't.

“So, yes, it’s very difficult for a

critic from the Fifties to understand what is a Powerbook 14UOC 133

running a 603E processor . . . Charlie Parker didn’t use this

stuff, so why is it needed?

“But if there is to be evolution in

the music we have to incorporate today's elements. just in the way

that Charlie Parker used a Selmer balanced-action 40,000 series

[saxophone]. This is new technology.

“When I started I was 21 and my music

was for that age group, because that's who I was playing to in pubs

and clubs. They can still relate to what I am doing. I’ve always

been trying to play music that is not just for a jazz-type audience.”

If Pine hasn't taken that “jazz-type”

audience with him he’s hardly worried.He may not sell as many

albums as a decade ago or command space in the fickle rock media any

more, but he’s carving a distinctive path and juggling his sense of

history with his new-found interest in hip-hop where "there’s

a parallel with kung fu movies."

"When you play jazz you go to New York and battle whoever is there. It`s like a martial art thing. The whole thing about scratching is, they have very similar battling contests where they say, ‘These are my skills' and they play something from Run DMC or Rock Raiders. Then someone else will come on and do it too, but improve it.

“They have the same kind of

discipline we have when we are playing a Charlie Parkeresque solo or

a line from Ben Webster. That's what I liked about it. It was like

tapping into a whole new language. I had to learn what those things

are and it`s a constant learning thing for me.”

What Pine has discovered though, particularly in America, is that his kind of jazz has outpaced its audience. Critics aside, he says, in America there is still a yawning gap between jazz artists drawing from hip-hop and contemporary music and an audience which prefers the comfort of familiar frames of reference.

“You say hip-hop and the people at

the Village Vanguard [jazz club] tear their hair out, no way do they

want to see a DJ on stage. But they are getting the message that

there is something new coming.”

It was also new for the members of his

band, he concedes. Bassist Reginald Veal may have just joined

Branford Marsalis’ similarly conceived outfit, Buckshot LeFonque,

which includes sampling and scratching, but he too was mystified when

DJ Pogo turned up in the studio.

“These musicians listen to everything

from George Clinton to Prince to Herbie Hancock’s Headhunters --

but there comes a time when you are actually in the ring and there is

an initial shock, and that's what happened to them. But this is not

Buckshot LeFonque because, although Buckshot is built on

sensibilities of popular music, they start with the drums, get a bass

player, overdub and edit.

“With me, we go into studio with five

days to record 10 tunes and play live. So I've found a sound which

nobody else is doing. a jazz album which incorporates hip-hop or even

drum'n'bass."

Pine isn't entirely breaking new ground

however. In New Zealand saxophonist Nathan Haines has been marrying

hip-hop and drum'n'bass sensibilities with jazz for many years and

has taken it to London and New York to some acclaim. But Pine’s

point is valid: if jazz is to survive then it needs to draw on the

world around it – just as John Coltrane played variations on My

Favourite Things or assimilated ideas from Indian ragas.

With colleges now turning out

technically skilled players in sharp suits however, Pine also knows

he has to stand out from the pack or, at age 32, be prematurely

considered of an earlier generation. And he’s doing that, not by

simply by embracing hip-hop but pursuing that journey to the urge

within.

Underground finds him reaching for a

spiritual in the tracks The Book of the Dead (inspired by a trip to

the Great Pyramid), acknowledging Alice Coltrane's Indo-jazz

explorations and drawing on meditation practices he observes.

“I do circular breathing where you

breathe in and out simultaneously and it takes you somewhere else and

refreshes you. All your concentration is on the breaths, which is

great for me as a woodwind player. It's just a very inspiring thing

for me to do and it's a way of connecting with my music.

“There are a lot of saxophone players

out there so I always have to think, ‘What am I doing to make it

worthwhile me doing this CD?’ I've gotta look into myself and find

something positive, and think, ‘What is it there that somebody else

might be interested in that's in my background?' That's what I’ve

got to look deeply into and reflect in a positive way.

“What I also know - and knew when I started and had all that publicity - is the most important thing in jazz is not the promotion. It's how you play the instrument."

post a comment