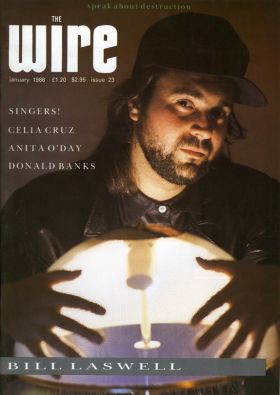

Graham Reid | | 13 min read

Material: Black Light (from Hallucination Engine, 1994)

The apartment seven floors up on Park

Ave South, just around the corner from the exclusive Gramercy Park

area of New York, is much as you might expect. Albums and CDs line

the walls.

Over there the new Last Poets 12-inch

single leans against the wall, on that shelf there the Yoko Ono CD

box set sits alongside books by Carlos Castenada. Photographs of

William Burroughs and Lee Scratch Perry, recording equipment, mobile

phone, odd paintings . . .

And as befits these rooms which are the

crucible of creativity, they are mostly darkened and closed in with

only the meanest of light coming through small windows to illuminate

the neatly filled bookcases.

It is also a place where the phone

rings incessantly -- but that’s hardly surprising because its

owner, Bill Laswell, is a man much in demand, be it as bass player,

producer or record label boss. But “facilitator” is a useful

partial explanation for what this intense, unsmiling, bearded

beret-champion does in this world.

When Bill Laswell enters the play,

things start to happen.

Herbie Hancock makes his techno-hit

Rockit, music from various cultures implodes through the studio

wizardry of Laswell’s sure hands, noisecore bands from Japan

explode, jazz saxophonists like Wayne Shorter find themselves with

itinerant Turkish musicians, a Greek guitarist records with the

drummer from the original 60s rock supergroup . . .

You name it, Laswell has worked with

it.

Jazz musicians? Yep, Laswell records

with German saxophone abuser Peter Brotzmann. Hispanic kids from the

streets of New York? Qf course. African musicians? All the time.

Yoko Ono? Yep, he produced Star Peace

for her. Iggy, Laurie Anderson, Peter Gabriel, Bootsy Collins, Mick

Jagger and the Swans then? ’Fraid so. Bill Laswell has worked with

them all . . . and sometimes simultaneously.

Take the Hallucination Engine album

which appears on Laswell’s Axiom label under the band name

Material. It’s a typical round-up-the-usual-suspects of Laswell

off-siders -- percussionist Aiyb Dieng, guitarist Nicky Skopelitis,

bassist Bootsy Collins, keyboardist Bernie Worrell --- but it also

hauls in Chinese singer Liu Sola (whose equally eclectic

suspect-heavy solo album is also released on Axiom). junk-writer Bill

Burroughs, violinist Simon Shaheen, reggae-riddum man Sly Dunbar,

Indian violinist Shankar, jazzman Shorter . . . and more.

Hallucination Engine is the world of

music scratched and sampled, distilled in the studio over a period of

time and shot through with hypnotic mantra-trance rhythms and searing

other-world sounds.

As the Axiom label logo proclaims:

“Nothing is true, everything is permitted.”

“Yeah, I do a project and then

another project and over the years other pieces [albums] come

directly from those experiences,” Laswell says as he positions

himself on a low cushion and makes disconcertingly level eye-contact.

“Over a period there are a lot of

first-time experiences with different textures, styles and people.

They are experimental points, many of which go on to become projects,

not necessarily for myself but for others.

“A lot of that record [Hallucination

Engine] is unrecognisable to me because it is out of context and I

have no memory of how it was done. There’s no story or concept or

plan. The plan is only to mutate the music and sounds endlessly into

another space and push it in different directions.

“If you just put those 24 tracks up

in the studio and listened, you wouldn’t relate it to the piece of

music that’s on the CD; a lot of things are changed or taken out .

. .”

Welcome, then, to the world of Bill

Laswell, the man who is most accurately called an alchemist and whose

Greenpoint Studios in Brooklyn were aptly described in a recent

Billboard as “an informal sonic laboratory-cum-refuge where

musicians are free to create without the burden of ticking clocks or

other non-musical hindrances."

For this sonic experimentalist, all

sound is created free and equal – and record companies are mostly

corporate criminals whose mandate is to make money and see musicians

as a hindrance to that process.

Here’s a man who genuinely believes

you can make great music with anybody ("not great classical

music, but you can find that feeling, pure part and quality in every

person and make that flow consistently as art”). And he should

know. He’s tried it over the past two decades and is as busy now as

he ever was, perhaps even busier.

“I've just finished a project for

Island Records of Haitian kids doing hip-hop called Voodoo 155 and a

whole lot of remixes, one, for Jah Wobble for a multi-media group

called EDN. I did the Scorn album - they are a big thing in England -

and have just made a band with [guitarist] James Blood Ulmer and

Ziggy Modeliste from the Meters.

“Tomorrow I've got a percussion

project with Aiyb Dieng, some Cuban people and Trilok Gurtu from

India is coming in with his tabla and drums. I'm meeting [jazz

saxophonist] Pharoah Sanders on Saturday morning, we’re supposed to

do a project. He’s playing great right now.

“Typical? Yeah . . . and unless

there’s commitment with a big screw and a deadline, I prefer to

keep thing pretty loose and let one project feed another.

“But I don‘t consider this work;

it’s life. If it was work, it would be something really ugly;

this is life and there’s only so much

of it, so you, have to get as much out of it as you can.”

Laswell -- whose personal and selected

discography runs to over 200 projects -- is certainly getting a lot

out of this lite. He has been to Japan about 50 times in the past

decade: “I just keep meeting more and more people there and I’m

interested in the hardcore scene there. It‘s a place where you can

work without compromise and people are straight.”

Two years ago he hiked up the foothills

of the Atlas Mountains in Morocco with a digital 12-track and

generator to record the fabled Master Musicians of Jajouka with whom

Ornette Coleman played and Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones also

recorded 25 years ago.

Laswell has done field recordings in

The Gambia, played alongside Indian, Turkish and African musicians,

those avant-garde types from Can, mixed Jimi Hendrix and spoken word,

has steered a couple of record labels and on the schedule this year

is a tour through China, Mongolia and across to Samarkand, staying in

tents and making music with Chinese, Japanese, African and American

musicians.

You name it, Laswell has done -- or is

about to do -- it. And in the rock culture in which he is most

clearly recognised, he carries a unique vision worth hearing these

days when lawyers, radio and accountants can fashion tastes, create

an audience where there was none and tie the whole thing to a

marketing plan designed to sell more jeans, lifestyle soft drinks and

T-shirts.

He shakes his head at why anyone would

want to be in A Band and work with the same people all the time:

"That’s unbelievable. Business, management and record

companies create that for their own ends and create the relationship

between the A&R person, his corporation, the artist-so-called,

his management, his producer, the engineers management . . .

"I now never do big projects for

financial reasons. I do them because I’m interested in them. Mostly

now I'm just working and money should come from work. Even those

things called 'bands' that I work with, it’s really just because

I’m interested, although I’m less and less interested in

configurations of people calling themselves bands, especially in the

competitive [rock] areas."

And that’s what makes Laswell the

facilitator and alchemist he is, although he denies he is doing

anything special.

"Not in time, not when you stand

and see time in a bigger space. At the moment it might just seem that

way."

And if you look away from the dark,

penetrating eyes to the mystical texts about dreams and illusions of

reality on the shelves behind the beret, the Laswell ideology starts

to make sense.

The fact sheet on this mahatma of musical synthesising begins simply enough: in the late Seventies he arrived in New York from Michigan where he’d played bass in various original and covers bands; in the Big Apple he added funk and fusion skills to the free jazz sounds he loved; he hooked up with the avant-garde of guitarists Fred Frith and Nicky Skopelitis; created the band -without-mission statement Material (with its revolving-door membership policy); hassled Brian Eno into letting him shove some bass lines down (some of which ended up on the Eno/David Byrne sample-and-hold My Life in the Bush of Ghosts album); found his way into production (Nona Hendryx, Material) and then cracked it with Herbie Hancock’s Future Shock album, which sprang Rockit.

It was that last outing that made

Laswell his name in the world of bigger budgets and saw him snapped

up by Mick Jagger (for She's the Boss) and, more improbably, Yoko

Ono.

Ono’s Star Peace album -- a typically

cringe-inducing outing salvaged only by Laswell’s hands-on sound

and his usual roster of fascinating playmates -- was taken on simply

for the experience of handling the larger budgets . . . and to get

him out of doing the Rolling Stones album he was offered at the time.

“It probably would have taken 10

years a song in Paris, and Yoko Ono’s seemed like a great

alternative to spending the next 25 years recording Johnny B. Goode

for the ten thousandth time,” he says with something approaching a

smile.

"I was just starting to do big

productions and get well paid, so I thought if I did that [the

Stones] I’d learn more about how that works and what really goes on

with those bigger operations and how to maintain, to budget, to

create those bigger things with travel and co-ordination.”

The appeal in the Ono album however was

his interest in her early period, when she'd been part of the Fluxus

avant-garde art network. But, as it happened, Ono was more keen on

pursing her woeful singing than the free-form screaming flights that

were the hallmark of her 60s sound.

“Musically I wouldn’t say anything

about it; it was more an experience and a curiosity . . . but I was

curious to goto that place [the Dakota] and I remember Bernie Worrell

and I went and wow, it was fun.” (Faint smile.)

But, as with the Jagger project, it

also put money in Laswell’s pocket, essential because he was also

in-house meistermind and producer at the Celluloid label and he’d

started to expand his horizons while finding the limits of audiences.

He had met Celluloid label boss Jean Karakos through Giorgio Gomelsky

(former Yardbirds and Stones manager with whom he’d connected on

arrival in New York) and over the next few years was the architect

behind some of the most innovative music of the decade, much of it

ignored by the mainstream music press.

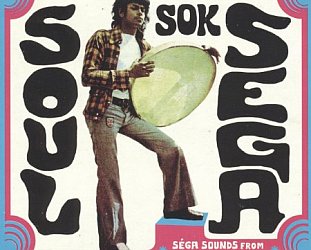

He teamed up John Lydon with Afrika

Bambaataa on the World Destruction single, pulled great Afrobeat out

of Nigerian funk king Fela Anikulapo Kuti, played with the Golden

Palominos (Michael Stipe singing the old Moby Grape classic Omaha)

and took turntables and hip-hop to Africa . . . much to the

irritation of the English rock scribes who nailed the accusation of

cultural imperialist on his door.

“All that activity happened because

of the genuine interest of Africans in trying something different. In

Senegal and The Gambia the kids wanted to have drum machines,

turntables and hip-hop. They wanted to experiment.

“There’s no sacred music -- that’s

the first thing. The music that’s happening around the world is

everybody’s music. You can discuss that with anyone and the only

ones who'll fight you are ethnomusicologists and book people.

"Master musicians all over the

world will tell you their music is free . . . with Celluloid I wasn't

even dealing with master musicians. I was dealing with pop people;

they weren't even great musicians."

But as Laswell notes in his intense,

direct manner, his style isn’t to sit around worrying; he keeps

moving.

"I'm not moving on, I'm moving

around.”

And that ethic has led him into the

parallel projects he can tick off: production jobs for Iggy Pop, the

Ramones, Motorhead, dozens of Japanese bands; bass whumping for the

likes of James Blood Ulmer, John Zorn and Tom Verlaine and, of

course, his own band Praxis (with P-funkers Worrell and Bootsy

Collins, drummer Brain and kiss-the-cosmos guitarist Buckethead). And

Last Exit, a noisy free-jazz band which -- up until the recent death

of its guitarist Sonny Sharrock – redefined noisecore jazzmetal and

got great press in England, a country Laswell has little patience

with.

They love Last Exit there, he sniffs,

but they’ll love anything that doesn't sell.

These days the projects still mount up

– he's confident of getting Omette Coleman and Bill Burroughs, both

friends, together for a project despite Coleman's aversion to

calendars and time in general.

But it is as label master of Black Arc

and particularly Axiom, his two-year-old label and personal project

of Island Records’ head honcho Chris Blackwell, that he is

increasingly occupied.

The Axiom catalogue already stretches

over cross-cultural. genre-defying albums which started with former

Cream drummer Ginger Baker's Middle Passage, through the

Brazilian/New York collision of Bahia Black’s Ritual Beating System

to the Afro-American politico-funk of former Last Poet Umar Bin

Hassan’s Be Bop or Be Dead. And now Hallucination Engine.

According to Seconds magazine, Axiom is

“William Burroughs’ city of Interzone come to life. Powered by

metaphysical principles, Axiom is populated by P-funk astronauts,

free-jazz alchemists, hip-hop soldiers and brigades of warriors from

Africa . . . more likely to be members of the Order of the Golden

Dawn than the Kiss Army.”

It can be startling stuff, not the

least for the way albums bleed into each other and can seem obliquely

cross-referenced. And in a world driven by cynical market forces,

Axiom's iconoclastic, releases which avoid the slam-dunk mentality of

rock or the cult-factionalism of jazz are finding their niche.

Laswell leans back in the half-light of

his room and in his quietly direct manner lets go a few thoughts.

He's been drawn always to North African and trance music and maybe

that's why he worked with the Aboriginal band Yothu Yindi on Freedom.

But unfortunately they come off like a

bar band, a bad Creedence covers band with a didgeridoo player, and

that‘s no reflection on them; that’s because they are a product

of their love for Slim Dusty and country music. Someone should take

the time -- someone not involved with rock'n'roll -- to take them

right back to their tribal rhythms and build things up from there.

When Bill Laswell talks about

cross-cultural outings typical of the Axiom label, you know the words

“world music" have no meaning any more.

“It’s a category,” he says

warily. "At least it means you’re not buying a Guns N’Roses

album, so it’s an indicator and speeds up the process of

discrimination. But more and more people won't ever leave Guns N’

Roses. I think that sensibility will actually get bigger, and that

control and manipulation will expand.

“What's going to be much more

interesting is the creation of an autonomous underground with young

people who realise you don’t need an understanding of business to

be an artist and create. You can network with people you trust and

keep it underground to keep it away from all those other areas.

“That’s what l’m looking to

build. Independent catalogues and networks, autonomous situations and

videos of all kinds will speed up the ability to transfer

information.

“Kids coming out of hip-hop with no

business background will be flung into situations where they are

dealing with vast amounts of information. That’s shock treatment

and that’s why it’s got to be kept underground . . . so all this

can get bigger.

“And it will.”

post a comment