Graham Reid | | 13 min read

George Harrison: This Guitar Can't Keep From Crying (alt version)

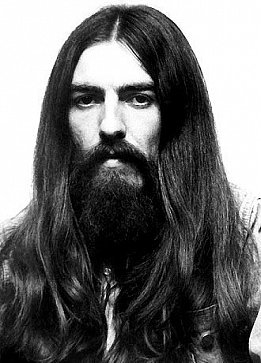

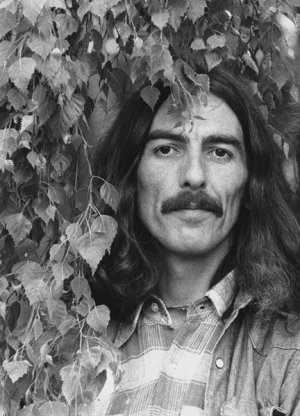

Perhaps he was no more contradictory than any of us, but because of his larger life George Harrison sometimes seemed to be a man of diametrically opposed parts.

He was a spiritual family man who could go on cocaine benders and wasn't above using his status as a former Beatle to pick up women.

He was a meditative man but among his chief pleasures was Formula 1. He was considered tight fisted and yet was enormously generous to friends and particular charities.

Depending on who you read he was a perfectionist as a guitarist in the studio who would labour to get things perfect, or he was so woefully inept that he just had to keep going over things to get them right.

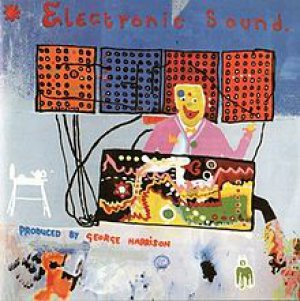

His was also a life that seemed dogged by litigation – post-Beatles business, being ripped off by a manger – but some of that was self-inflicted: both his biggest hit (My Sweet Lord) and his smallest selling album (Electronic Sound) were mired in controversy and accusations he had simply ripped off others.

He was the former Beatle who seemed most resentful of those years and yet frequently revisited them in songs which referred to that past (Here Come the Moon, This Guitar Can't Keep from Crying) and in video clips (All Those Years Ago).

He famously berated an audience on one

of his tours where Ravi Shankar opened to the crowd's rude

indifference by saying he'd die for Indian music but not this,

pointing at his electric guitar.

He famously berated an audience on one

of his tours where Ravi Shankar opened to the crowd's rude

indifference by saying he'd die for Indian music but not this,

pointing at his electric guitar.

He wrote songs as beautiful as Something and Here Comes the Sun and as innovative as Love You To, Long Long Long and I Want to Tell You . . . but also expected his fans to endure hack work like Ding Dong and his personalised cover of the Everly Brothers' Bye Bye Love in which he made snarky comments about his former wife Pattie Boyd and her new lover Eric Clapton, both of whom he also remained close friends with.

If his solo career was one of diminishing financial returns after his monster All Things Must Pass (1970), it's also possible to say there was some unfairly overlooked material scattered about on his albums. Ironically though not enough for his record company who, when they went about presenting a “best of” collection, included his Beatle-era songs (seven of the 13) much to his annoyance and humiliation.

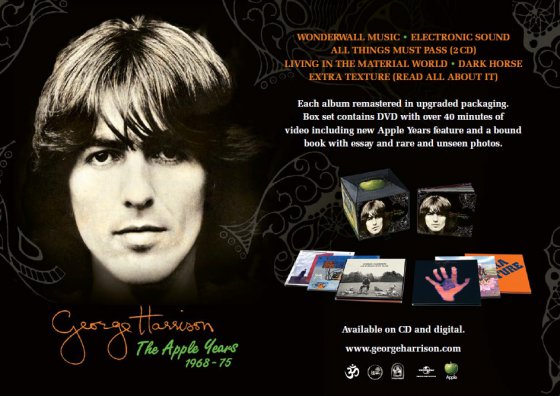

Some years ago a box set pulled together the albums on his own Dark Horse label, but now comes the companion box set George Harrison: Apple Years 1968 – 75 with a DVD of his music videos, plus a booklet.

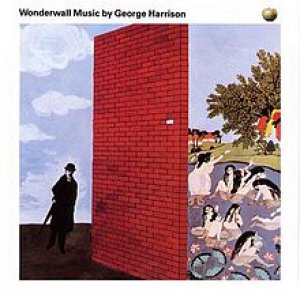

The set of remastered albums includes Wonderwall Music and Electronic Sound (both released when he was still a Beatle), All Things Must Pass from late '70 (again, it has seen a number of reissues), Living in the Material World ('73), Dark Horse ('74) and Extra Texture ('75). And the songs sound much better, they seem to have much more presence than the old vinyl which I faithfully pulled out to make the comparisons.

So here's what's in the box . . .

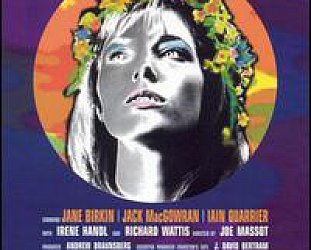

Wonderwall Music: Nominally the

soundtrack to the film of the same name by Joe Massot. But if the

music didn't make much sense or have any coherence (across 19

separate pieces there were Indian ensembles, faux country'n'western,

psychedelic, nods to the blues and music hall) it's because that's

what the cult film was like.

Wonderwall Music: Nominally the

soundtrack to the film of the same name by Joe Massot. But if the

music didn't make much sense or have any coherence (across 19

separate pieces there were Indian ensembles, faux country'n'western,

psychedelic, nods to the blues and music hall) it's because that's

what the cult film was like.

In the film a straight, buttoned-down Englishman man glimpses the exotic other (free love, hippies, breasts) and so we travel between these worlds.

As did Harrison who went to India to record some players there (including the great Shiv Kumar Sharmar on santoor) and also held loose sessions inAbbey Road and De Lane Studios in London. Eric Clapton dropped by (that's his backwards guitar on Ski-ing) and Peter Tork of the Monkees was around long enough to briefly play banjo.

The Indian pieces are the most successful for their dreamy quality but the real wake-up is the five-plus minutes of Dream Scene which was by far the most psychedelic and out-there piece by any Beatle to that time, and towards the end you can almost anticipate Lennon's Revolution 9 coming in.

Some really pretty pieces also – side two is gem-encrusted oddness – plus some oddball stuff scattered about . . . and although Harrison took a backseat as a player for some of it, an album worth discovering. In retrospect one of the most interesting and courageously different of his solo albums.

The extra tracks include an Indo-pop piece Almost Shankara, his old pals from Liverpool the Remo Four who helped on the sessions with In the First Place (very Blue Jay Way) and an alternative instrumental take of what became The Inner Light. All good.

In a short introductory essay Nitin Sawhney writes of how the album was "a standalone vision [which] embraces a glorious multiverse of sonorous vignettes like nothing I've ever heard. It speaks of a fearless heart."

Electronic Sound: One of the

pleasures of being a Beatle was that people would offer you the

latest pieces of recording technology or unusual instruments, and

Harrison was rather up for that.

Electronic Sound: One of the

pleasures of being a Beatle was that people would offer you the

latest pieces of recording technology or unusual instruments, and

Harrison was rather up for that.

He'd heard about the Moog synthesizer and so met up with Beaver and Krause who were part salesmen/part musicians introducing this new fangled thing far and wide. When a Beatle showed interest they must have been thrilled.

Not so later, because Harrison had an engineer record Bernie Krause showing him some of the possibilities on the equipment while they were in a studio in California.

Shortly after, on his return to Britain, Harrison bought a Moog (a huge chunk of equipment) then called Krause over to London where they set it up in Harrison's house, smoked a joint and Krause played the machine for a while. Then Harrison played Krause a tape -- which Krause recognised as the same piece he'd done in California -- and told him he'd be putting it out on an album and if it made any money he'd send him (Krause) some . . . if it made any.

The first side of Electronic Sound entitled Time and Space is apparently exactly what Krause played that day in California. If you look closely at the cover you can see Krause's name there (misspelled) but he insisted it be scribbled out.

The other side Under the Mersey Wall further confirms Harrison's later dismissal of the album as “a load of rubbish”. It's just Moog noodling, and whether they be by Krause, a Beatle or a mouse on acid jumping all over it makes little difference.

The Moog went to Abbey Road and was used on the album of the same name.

In his essay Dhani Harrison has a lovely story of how he came across it, drawn in by the cover at which his dad explains to him, and Tom Rowlands of the Chemical Brothers tells how he was first attracted by the weird cover which he now has hanging on the wall of his studio "next to my own Moog modulator, beaming inspiration straight into my brain".

Two solo albums in and Beatle George was hardly setting the world alight with these side projects.

Fortunately for him the Beatles didn't last much longer and so . . .

All Things Must Pass: It was

“like diarrhea”. That was the charming but perhaps accurate

description Harrison offered of finally managing to get his own songs

out there after being stymied for so long inside the Beatles.

All Things Must Pass: It was

“like diarrhea”. That was the charming but perhaps accurate

description Harrison offered of finally managing to get his own songs

out there after being stymied for so long inside the Beatles.

Prompted by the success of his songs on Abbey Road (Here Comes the Sun, Something) and the high regard he was held in by his peers (among them Dylan whom he co-wrote I'd Have You Any Time and If Not For You), Harrison called on a roster of great players – Clapton and those who would become Dominos, Badfinger, Billy Preston, Ringo, Ginger Baker, pedal steel player Pete Drake and others – for lengthy sessions which were more like a gathering of talented pals.

“He had the finest, the crème de la crème at his disposal,” said Bobby Whitlock later, “and he wasn't telling anybody what to play. He just let it roll.”

The result across four sides of the triple albums set (now a double CD) were some of Harrison's finest songs brought into widescreen life by producer Phil Spector (who wasn't allowed to bring his gun into the studio). Today it sounds over-produced in places – especially since the release of the Early Takes Vol 1 album of demos – but it remains an impressive achievement. The jam sessions are the least of it.

The version here is the 2001 reissue which came with extra songs including Harrison's revisit to and rejig of My Sweet Lord, excellent acoustic versions of Beware of Darkness and Let It Down, and the instrumental backing track for What Is Life.

The cloud hanging over the album however was the disputed origins of My Sweet Lord which those who were there say came from a Delaney and Bonnie gospel jam when Harrison was present. They were improvising on “my sweet Lord” using the Chiffons' He's So Fine chords (which Ronnie Mack wrote). Harrison found himself in court when the songwriter Mack's publishers Bright Tunes accused him of plagiarism.

Harrison's solo career had got off to a faltering, then fine, then fraught start. And it took a while to get back on track because he took time away from his own work to pull together the Concert for Bangladesh shows and album in '71/'72.

Living in the Material World: After the debacle which followed the extraordinary Concert (wrestling to get the album and film released), Harrison was doubtless weary and in places this album suffers from some of that.

Living in the Material World: After the debacle which followed the extraordinary Concert (wrestling to get the album and film released), Harrison was doubtless weary and in places this album suffers from some of that.

The opener Give Me Love ("help me cope with this heavy load") has a sense of pleading and urgency, and Sue Me Sue You Blues ("bring your lawyer and I'll bring mine . . . all that's left is to find yourself a new band") reflected on the post-Beatles litigation.

He fondly mentions his former bandmates in the title track, but it is of them when they were young and starting out.

Try Some Buy Some was a song he wrote for and recorded with Ronnie Spector (it did nothing for either party) and Harrison simply recycled the backing track behind his strained vocal.

But the album also has considerable charms and as an Australian writer at the time noted, "oftentimes the music is a more truthful guide to the sense of the lyrics than the words themselves. Harrison is not a great wordsmith but he is a superb musician. Everything flows, everything interweaves. His melodies are so superb they take care of everything".

When he nailed it (The Light That Has Lighted the World, heard in a superb demo on Early Takes Vol 1) this album can be very moving.

But the tone is subdued and Harrison sounded battered by recent events and the Beatle legacy (Who Can See It another standout). In other hands (Beatle band hands?) Don't Let Me Wait Too Long could have been a very decent stab at the pop charts. And Be Here Now remains among his finest work, every bit as emotionally revealing as anything by Lennon.

The three additional songs are the single Banga Desh, Miss O'Dell (the b-side of the Give Me Love single) and the especially good Deep Blue (the b-side of Bangla Desh) written when his mother was seriously ill a few years previous.

He sounded -- and indeed was -- emotionally isolated at this time, and gloss of his position as a revered former Beatle/Bangladesh patron and spiritual guide was starting to tarnish. And worse, he was increasingly starting to proseltyze in way that many would find finger-wagging and scolding. He was sounding ungracious and irritable, but wrapping the message up in melodically interesting songs.

It was a big album for him at the time and deserves a fair re-hearing.

Dark Horse: By the time of this sloppy and slapdash album Harrison was damaged goods in the rock world he once inhabited and towered over.

Dark Horse: By the time of this sloppy and slapdash album Harrison was damaged goods in the rock world he once inhabited and towered over.

His American tour post-Material World was close to a disaster as he'd lost his voice, fans wanted Beatle George not the new music, and the few Beatle songs he did play he seemed to want to sabotage. Shouting hoarsely "something in the way she moves it" rather undermines that beautiful ballad. He was truculent and resentful in the few interviews he begrudgingly granted.

The album opens with a lightweight instrumental Hari's On Tour (Express) featuring the LA Express band headed by saxophonist Tom Scott, and this is the album which has that version of Bye Bye Love and the lazy Ding Dong on it. That's three out of the nine track which don't warrant repeat play . . . but as always he could craft a lovely melody.

So Sad mightn't find him in great voice but you can hear a fine song in there as he explores his inner loneliness ("he feels so alone with no love of his own"); Maya Love is a kinda funky workout with Billy Preston on electric piano; Far East Man is a decent blend of blue-soul and late night ennui dedicated to Ravi Shankar and co-written with Ronnie Wood (whose own version with many of the same musicians appeared on his I've Got My Own Album To Do with Harrison guesting).

More interesting than exceptional, Simply Shady catalogues how he "came off the rails so crazy" and soaked himself in booze and whatever after he broke up with Pattie.

So Dark Horse was an uneven album from a man who was moving further away from the pop culture in which he once occupied a central place, and more into introspection and spiritualism with professional pals who -- with the exception perhaps of Preston -- could deliver the good but not the soul some of his songs seemed to require.

The additional tracks are a very good demo of the title track and a song with a title which says so much: I Don't Care Anymore.

Extra Texture (Read All About It): Harrison's years on Apple came to an ignominious end with this album which kicks off with the remarkably upbeat rocker You.

Extra Texture (Read All About It): Harrison's years on Apple came to an ignominious end with this album which kicks off with the remarkably upbeat rocker You.

But, as Greame Thompson noted in his recent Harrison biography Behind That Locked Door, after that Harrison "seemed intent on making the blandest and most cravenly inoffensive record he could".

Perhaps that was because he had been so wounded by the criticisms he'd received, more likely he just couldn't be bothered with the workld of rock as it had shaped up in the five years since his greatest successes.

Even he admitted it was "a bit depressing, actually" -- although there are other ways to read it. It is his least overtly spiritual album, he plays as much keyboards as he does guitar, there is fine playing throughout from the likes of keyboard players Gary Brooker (Procol Harum) and David Foster, and guitarist Jesse Ed Davis.

Always a thinker -- if sometimes a finger-pointer -- he allows the melancholy and string-enhanced The Answer's At the End makes a lovely plea, "don't be so hard on the ones you love" and might not have sounded out of place on All Things Must Pass if it had been handed to Phil Spector to produce.

The best track might just be the moody Tired of Midnight Blue in which he admits to getting weary of indulging himself in nightclub "naughtiness" and just wanting to be back home. He fills it with dog-tiredness and a sense of self-loathing.

The look over his shoulder on This Guitar Can't Keep From Crying is a much better song than it seemed at the time, when it was read (perhaps rightly) as a lesser rewrite of one of his most memorable songs, but the extra track is a fascinating undated update with Dhani, Ringo and Dave Stewart.

His MOR ballad Ooh Baby and World of Stone suffer from his thin vocals (the former should have gone to Smokey Robinson) and the jokey closer His Name is Legs for his pal Legs Larry Smith of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band doesn't live up to its opening line that "everything is tickety-boo".

It was a quirky end to his career on the Apple label he helped establish (on the label he pointedly has an apple eaten down to the core), but a pointer to a very different path he would take when his indulged his eccentric side and underwrote a film for his Monty Python pals, Life of Brian.

Harrison always seemed to enjoy films -- not always being in front of the camera however -- and his enjoyment in the British eccentricity of Monty Python's irreverent skits was something he increasingly brought to his own videos.

The DVD here -- housed in a hardback booklet with an essay and photos -- collects together a Harrisongs overview montage directed by Olivia Harrison; the interesting eight minute featurette which came with the expanded 2001 reissue of All Things Must Pass ("It's not exactly an EPK [electronic press kit]" but it is a threat to world order as we know it," he quips); and the EPK for the Concert for Bangladesh reissue in 2005.

The DVD here -- housed in a hardback booklet with an essay and photos -- collects together a Harrisongs overview montage directed by Olivia Harrison; the interesting eight minute featurette which came with the expanded 2001 reissue of All Things Must Pass ("It's not exactly an EPK [electronic press kit]" but it is a threat to world order as we know it," he quips); and the EPK for the Concert for Bangladesh reissue in 2005.

There also a slight "making of" featurette about Living in the Material World; a live clip from his '91 tour in Japan (a nervous looking Harrison on a very good version of Give Me Love); an alternate take of Miss O'Dell; his dobro demo version of Sue Me Sue You; an excellent acoustic demo of Living in the Material World (which came with the deluxe edition of the Martin Scorsese bio-doco of the same name) and the clip for Ding Dong in wich he parodies hi Beatles '64 look and his current image as an Indo-obssed fellow.

There are also still photos of a dress-up garden party at the mansion for Dark Horse.

You get more of a sense of how serious or wry Harrison could be here than across some of the albums.

It's unlikely this beautifully packaged box set -- all the albums now available individually on iTunes -- will prompt a major reassessment of Harrison's music. But freed of their time (and the artist himself) you can appreciate the songcraft and honesty much more.

He frequenty wrote beautifully melodic songs -- ironic given his first songs in the Beatles such as Don't Bother Me, I Need You and If I Needed Someone were all very monochromatic -- but far too often lumbered them with worthy lyrics which simply clunked awkwardly and brought skyward tunes down to earth.

However, aside from his finest albums All Things Must Pass and Living in the Material World plus the little nuggests scattered about, you do come away with admiration for George Harrison's music and integrity when he was at the top of his game . . . and how peculiar and terrific Wonderwall Music was.

And is.

.

For more on George Harrison (including obscurities and such) go here.

For part two of this overview of George Harrison's solo career go here.

.

.

.

post a comment