Graham Reid | | 5 min read

John Lee Hooker: It Serves Me Right to Suffer (2002, with Dickey Betts on guitar)

John Lennon once said the blues was a

chair. Not a fancy chair, just the first chair.

No, it doesn't make much sense - but

you know what he means. And by making this analogy he placed himself

alongside a swag of blues artists who have their own pithy statement:

the blues is a feeling, the blues is healing music, and so on.

John Lee Hooker – who died in 2001 aged 88 –

had a few such soundbite sayings, but he also had something more: a

capacity for re-invention that Madonna and David Bowie would admire.

He was big in the Sixties when he was known as the Boogie Man after his first hit, Boogie Chillen' in 1949, was mostly out of the spotlight in the Seventies, and came back in the late Eighties as The Iron Man (after an appearance on Pete Townshend's album of the same name), then the Healer, Mr Lucky and a few other names, each appended when he released a new album of that title.

And the Hook released a lot of albums -- amazon.com lists

almost 300.

And it's fair to note he wasn't above

repeating himself. The man who made an art form out of an earthy and

often sexually charged "well, well, well", "hmmm,

hmmm, hmmm" or "baby, baby, baby" would revisit his

classic songs year after year.

You don't have to go far to find a Hook

album with his signature tunes, Dimples or Boogie Chillen', on them.

But if you have a distinctive sound you

might as well just ride it, as he acknowledged.

"They used to call it boogie

woogie," he said, "and I just updated it. Just a straight

boogie with no changes, a rocking beat. The bass beat on the drums

and some funky beats on the bass, then everybody just rides. When we

play a boogie the whole house gets up. We ride it like a pony."

What separated him from others singing

their same old songs was a primal voice that seems to come from the

soil, charged with lightning and capable of conjuring up dark voodoo.

The Hook could be sexual to the point

of an X-rating (the creepy sensuality of The Hot Spot with Miles

Davis, recorded in 1990) but also just plain mean spirited (his

acoustic recordings of the Fifties).

The Hook could be sexual to the point

of an X-rating (the creepy sensuality of The Hot Spot with Miles

Davis, recorded in 1990) but also just plain mean spirited (his

acoustic recordings of the Fifties).

And his style -- repetition, simple

lyrics into which he poured meaning and primitive tunes -- allowed

for a musical dialogue between that voice and his guitar. After the

mid-Sixties -- when the Animals backed him, the first Delta bluesman

to work with an English rock/r'n'b band -- he was increasingly heard

in band settings.

His raunchy style influenced a

generation of British r'n'b artists: David Bowie and the Who's Pete

Townshend acknowledge him; the Yardbirds, the Animals, the Spencer

Davis Group and Them (with Van Morrison on vocals) used his music as

their foundation.

His songs were later covered by ZZ Top,

the J. Geils Band, the Doors, the Allman Brothers Band, George Thorogood

(many times), Stevie Ray Vaughan, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen and

Tom Petty.

Listen to Hooker and you can hear where

Jimi Hendrix got Voodoo Chile, Red House and Foxey Lady.

"I have inspired so many

rock'n'roll singers and stars," he growled at me in late 1990, "more than any other blues singer. I got music for all

ages, I got something for everybody."

His genius was recognised right from

when Boogie Chillen' sold a million, and late in life he enjoyed

enormous popular success -- and a couple of Grammys -- when Santana,

Bonnie Raitt, Robert Cray, Thorogood and other famous fans lined up

for the Healer album in 1989.

The Hook, who seldom smiled and

remained an impassive figure behind shades and dressed in natty dark

suits, was getting his dues.

Not that he was a broken-down bluesman.

He had a large property in San Francisco and was smarter than most in

securing royalty payments.

Hook died in June 2001 (he had spent

his last Saturday night on stage) but he is survived by astute estate

management and the John Lee Hooker Family Limited Partnership.

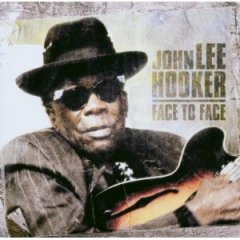

The first trickle-down from the family,

with liner notes by his daughter Zakiya, was Face to Face recorded in

his final year and released in 2003, with a stellar cast that includes Morrison,

guitarists Elvin Bishop, Dickey Betts, Johnny Winter, Roy Rogers and

Thorogood, Jefferson Airplane bassist Jack Casady, pianist Johnny

Johnson and others.

This is Hooker as r'n'b rocker, riding

those grooves for the umpteenth time yet still finding meaning and

menace in classic songs like It Serves Me Right To Suffer, Mean Mean

World, and inevitably Dimples (with Bishop, soundalike Morrison and

Jimmy Pugh on organ) and Boogie Chillen' (a duet with Thorogood).

The title track with Winter on slide is

archetypal Hook: his signature style of repeated phrases (which

Morrison adopted early in his career) and a growl of affection which

is spooky. A standout is the elemental Mad Man Blues with just Rogers

and Thorogood on guitars.

The Hook gets sentimental with the

gorgeous, string-splashed ballad Six Page Letter and pulls out the

soul with Funky Mabel.

But mostly this is a punchy, blues-rock

collection which includes some new songs: Loving People and Rock

These Blues; the former snakey Chicago-styled blues which finds the

old boy in a forgiving mood ("lovin' people keep me happy");

the latter a deep throbbing boogie adapted from his Rockin' Chair,

with Zakiya on vocals as the betrayed lover.

John Lee Hooker influenced more than

one generation of rock musicians and dozens, if not hundreds, of

blues singers. These sessions are evidence that even in his final

months his power was undiminished.

Pull up a chair.

The illustration at the head of this article is by Serqan, see here.

Like this? Then check out the interviews, reviews and overviews at Blues in Elsewhere.

post a comment