Graham Reid | | 10 min read

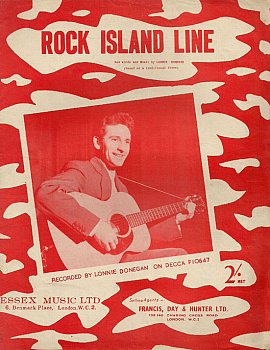

Rock Island Line by Lonnie Donegan

As with so many historic moments, at the time it was mundane . . . but became culture changing.

This one was something as ordinary as this . . .

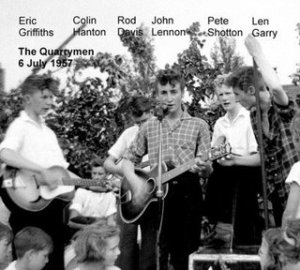

By all accounts July 6, 1957 was an unseasonably warm day in Liverpool, even for summer. It was the time of galas, garden parties and fetes.

In the middle-class suburb of Woolton, St Peter's church was hosting a popular fete and local performers were invited to appear.

One of those was a schoolboy skiffle group, playing in that musical style which was all the rage with teenagers at the time because anyone with a cheap acoustic guitar, a washboard from Mum's laundry as a percussion noise and a tea-chest bass could knock it out.

Down in London, in the wake of Lonnie Donegan's breakout skiffle hit Rock Island Line of the previous year, the press estimated there might be between 400 and 500 skiffle groups. Even up in Liverpool it was maybe as many as 200.

And at St Peter's there was one such group, fronted by a 16-year old schoolboy in an open-neck check shirt and surrounded by a few mates.

They played a couple of sets that day, maybe three, before a loose jam in the church hall that evening, and they padded their skiffle set out with the first flushes of rock''n'roll (Gene Vincent's Be-Bop-A-Lula).

At some point in the afternoon when the band left the makeshift stage Ivan Vaughan, a friend of the guy in the check shirt, introduced another young lad, just a few weeks past his 15th birthday, to the frontman of the group: The Quarry Men.

And on that summer

day the boy who would become the famed John Lennon, the one in the check shirt, met Paul McCartney.

And on that summer

day the boy who would become the famed John Lennon, the one in the check shirt, met Paul McCartney.

After that everything changed.

It seems odd in retrospect that it should have been skiffle not the emerging rock'n'roll that brought them together, but playing in a rock'n'roll band was a distant dream for British teenagers without the coin to buy the gear, or the ability to play it.

Skiffle was easy, upbeat and required few skills. McCartney later recalled that what he admired immediately about Lennon was he clearly didn't know the lyrics to some of the songs . . . but that didn't stop him.

“My first impression,” McCartney would say later, “was that it was amazing how he was making up the words. He was singing Come Go With Me by the Dell-Vikings and he didn't know one of the words.

“He was making up every one as he went along. I thought it was great.”

Skiffle was everywhere in Britain in 1957 after Donegan's '56 hit (and its follow-ups). Consider those vague numbers of bands in London and Liverpool and expand them out across the country.

That translates to

many, many hundreds if not a few thousand groups of young people –

boys predominantly, of course – bashing out Rock Island Line, even

if they didn't have a clue what it was about or where the song came

from.

That translates to

many, many hundreds if not a few thousand groups of young people –

boys predominantly, of course – bashing out Rock Island Line, even

if they didn't have a clue what it was about or where the song came

from.

It's a common myth that in Britain before the Beatles there was Cliff Richard and the Shadows, a few one-off rock'n'rollers (Billy Fury from Liverpool and Adam Faith among the more durable out of Larry Parnes' find-them/rename-them school of star-making) and not much else.

But there was an enormous amount of skiffle activity going on and, unlike American rock'n'roll which was made by artists older than the audience, this was a music made by young people for young people.

For the first time in history the performers and the audience were much the same, something that wouldn't happen again until punk two decades later.

That the skiffle movement went largely unrecorded by these masses of mostly informal bands meant it was swept away quickly from the public consciousness with the arrival of the Beatles and the British Invasion of the US.

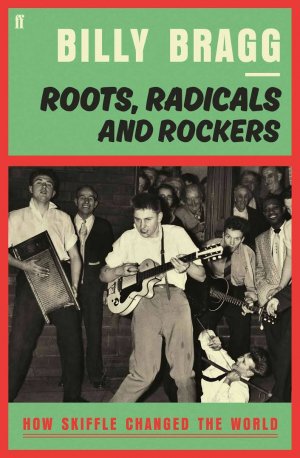

But, as musician/writer Billy Bragg notes in his new book Roots, Radicals and Rockers; How Skiffle Changed The World, this period after Elvis Presley's Heartbreak Hotel hit in '56 and Cliff Richard's chart dominance in the early Sixties with pleasant pop was not the “dead ground of British pop culture” it has often been made out to be.

Skiffle, trad jazz

and flickers of rock'n'roll were everywhere.

Skiffle, trad jazz

and flickers of rock'n'roll were everywhere.

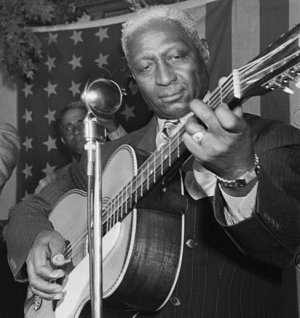

Skiffle was a uniquely British version of American folk-blues and drew from the likes of Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter who popularised the old Rock Island Line song. It had been first recorded in '34 by prisoners in Arkansas who were taped by archivist John A Lomax, three years before he recorded it again in Washington with Lead Belly.

The song itself is an odd one, writes Bragg. It appears to be about a man smuggling pig iron (what the hell is pig iron?) on the railroad and talking his way past the toll operator near New Orleans with smooth patter.

But as Bragg notes in a fascinating preamble about American railroads in his book, the Rock Island Line didn't go to New Orleans and there never were toll gates on those railroads. And of course although Lead Belly is credited with the song it existed before him.

Even more odd is the history of Lonnie Donegan's hit version: he'd recorded it on July 13, 1954, a full 18 months before it took off.

As Bragg says, “So what is really going on here?”

Oh, and as we discover in Bragg's pages even the word “skiffle” has a different meaning on each side of the Atlantic: in the US it was used to describe something like a rent party, but in Britain the term was hijacked to apply to this suddenly emerging musical style.

That “skiffle” idea had formed around an informal “breakdown” in the jazz set of Ken Colyer's Jazz Band (among others) when, in Colyer's instance, Donegan would step forward and play and sing while some of the others took a breather for a pint and a cigarette.

So yes: “what is going on here?”

These mysteries and Bragg's extensive digressions into popular American and British culture at the time form the backbone of his book which opens with a discussion of railways and Rock Island Line, but then rolls back the tape into skiffle's pre-history to explore New Orleans jazz.

It ends with that

historic moment in Liverpool which, in many ways, would flag the end

of British skiffle forever . . . although by '62 when the Beatles

first recorded (Love Me Do) it had diminished to a trickle anyway.

It ends with that

historic moment in Liverpool which, in many ways, would flag the end

of British skiffle forever . . . although by '62 when the Beatles

first recorded (Love Me Do) it had diminished to a trickle anyway.

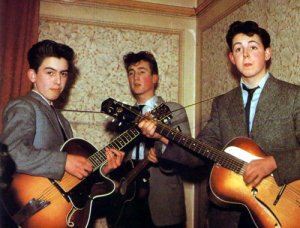

The young Beatles of Lennon and McCartnery with George Harrison, then Ringo Starr -- and their first songs Love Me Do then Please Please Me -- were just the final nails in the skiffle and trad jazz coffin.

A new generation five years on from Donegan looked at acoustic skiffle as a slightly embarrassing and most certainly unsophisticated form.

Skiffle's peak in Britain came in early '56 with Donegan when the song, released in November the previous year, climbed into the charts.

And although there really was no such thing as skiffle in the US – even though Donegan was well received there – it did have a minor impact: the first song Art Garfunkel bought was Lonnie's Rock Island Line.

But there was an uncanny coincidence in both Donegan's recording 18 months previous and its release.

Donegan originally sang it as filler on an album for the Chris Barber Jazz Band album – which had split off from the Colyer outfit – and, an unbeknownst to him or anyone else, he'd sung it just a week before the young Elvis Presley recorded That's Alright Mama at Sun in Memphis.

And when Donegan's song was eventually released Bill Haley's Rock Around the Clock was topping the British charts.

“Had someone at Decca,” writes Bragg referring to the Barber/Donegan label, “spotted that the word 'rock' suddenly had currency with teenagers?”

Certainly Charles Grove writing for the NME at the time said, “it has even been suggested that Rock Island Line is selling on the strength of its title alone”.

But that would be unfair because Donegan's song, which admittedly starts very slow with a spoken word part (and was easy to parody), gains momentum and energy as it goes.

There is however a weird historical irony there about the twin birth of these two movements – rock'n'roll and skiffle: Elvis was born a twin but his sibling died at birth . . . and the skiffle twin didn't last much longer either.

Skiffle as the Brits knew it had

emerged out of the trad jazz sound of New Orleans which had been

brought to Britain by Ken Colyer, one of the more interesting,

opinionated and probably personally unpleasant men in the music scene

at the time. But he was undeniably a musical groundbreaker.

Skiffle as the Brits knew it had

emerged out of the trad jazz sound of New Orleans which had been

brought to Britain by Ken Colyer, one of the more interesting,

opinionated and probably personally unpleasant men in the music scene

at the time. But he was undeniably a musical groundbreaker.

The dogmatic Colyer had explored New Orleans jazz at its source when, as a merchant seaman, he'd made repeated attempts to get there and finally succeeded in the early Fifties. When he returned home his adventures with authentic jazz were preceded by stories in the music press . . . and he had the additional cachet of spending time in prison in Nawlins for playing with black musicians.

He was feted and hailed on coming back, but he'd also had his opinions entrenched.

For him, there was traditional jazz of the Nawlins style, and all else was to be rejected. Colyer had seen the undisputed truth . . . and thereafter, as has happened so often when purists ring-fence their ideological position, the lines were drawn.

At the time that fence – in fact a very high wall in Colyer's opinion -- was between the trads and the modernists. And trad was where it could only ever be at for him and his acolytes.

But while jazz players, scholars and students of this genre argued about “authenticity”, the working class teenagers – as Bragg notes – looked and heard something else.

They loved the excitement and simplicity of those moments when Donegan stepped up and in an unadorned style played this fast, new, simple and pop-framed sound which became known as skiffle.

It was beat-driven, contained lyrical mysteries (that “pig iron” thing) and easy to participate in because it was cheap to make a passable noise in the style.

Hence, suddenly, thousands of skiffle groups.

Bragg's readable book on all this explores more than just skiffle however.

It embraces the broad, if sometimes readably superficial, social history of post-war Britain accounting for the rise of Soho nightclubs and sleazy after-hours life in London where outsider bohemian painters rubbed shoulders with callow youth; of coffee bars like the famous 2 I's where Tommy Steele among many others was discovered; through the origins of the drape-jacket Teddy Boys; onto those train tracks of rock'n'roll and skiffle running alongside each other; explaining why duffle coats became so de rigueur for beatniks and student; exploring the impact of television and kitchen sink dramas (and John Osborne plays) and much more.

Including how the end of National Service liberated a generation of young men – Lennon and his peers among them – to actually enjoy being teenagers without the shadow of compulsory military service hanging over them like a spoiler.

Given that scope, sometimes Bragg's book can come off as diluted Wikipedia entries, and more detailed coverage of the teenage territory is covered better in Mark Lewisohn's Tune In about the Beatles pre-fame years and Pete Frame's The Restless Generation.

However Bragg's story offers character studies (some of them engaging people, others you wouldn't want near your liquor cabinet), lively anecdotes, and hilariously alarmist comments about teenagers' tastes from music magazines and newspapers of the day . . . a few of which sound eerily familiar even now.

And then there is the 20/20 hindsight of the absurdity of rear-guard actions by jazz and folk purists – who still haven't learned it seems – trying to keep the youthful and energetic barbarians outside their gates. To no avail.

Those disrespectful and heretical teenagers inevitably invaded the battlements of adult culture and earnestness, and by the early Sixties it was game-over for skiffle, trad jazz and arguments about New Orleans purity.

It was also a class war in many ways, and guess who won?

It was always going to happen.

As a boy, The Who's Pete Townshend's dad took him to see Ken Colyer's band and in that instant – a guitarist centre-stage not a horn player – he glimpsed his future. And therein lay the end of skiffle.

The kids occupied the ground created by

nascent rock'n'roll and skiffle, plugged it in, turned it up loud and

. . .

The kids occupied the ground created by

nascent rock'n'roll and skiffle, plugged it in, turned it up loud and

. . .

In his final pages Bragg simply offers a synopsis of all those British artists – many household names in a way the skiffle players never could have been – who got their legs in skiffle and then turned to more earthy rock'n'roll which was in the ascendent.

It's a helluva list: Dave Clark, Peter Asher (of Peter and Gordon), Alan Price and Hilton Valentine who joined forces in the Animals, Paul Jones who would front Manfred Mann, Wayne Fontana, Bill Wyman of the Stones who made himself a tea-chest bass, Chad Stuart (of Chad and Jeremy), Van Morrison, members of Led Zeppelin, the Honeycombs (Have I The Right produced by Joe Meek), Dave Davies of the Kinks, most of The Hollies and Cream . . .

It's weirdly wonderful to imagine the teenage David Bowie enthusiastically singing Donegan songs at a Scout camp . . .

Billy Bragg's shelf-filling reference book maybe oversells skiffle in some ways – that subtitle? – because, of itself, cheap skiffle didn't exactly change the world.

But British teenagers at the tail-end of the period he works toward -- those caught between the Elvis/Chuck/Buddy/Jerry Lee and whatever future might come their way -- most certainly did.

And it's fair to say that maybe, just maybe, the change unwittingly happened on an unseasonably hot summer's day in unsuspecting Liverpool in '57 in the most mundane of circumstances.

But, at that time, who could have possibly have known . . .

ROOTS, RADICALS AND ROCKERS; HOW SKIFFLE CHANGED THE WORLD by Billy Bragg. Faber and Faber, $45

post a comment